Add the computer and communications revolution to the list of fundamental changes that are widening the political divide between red and blue America.

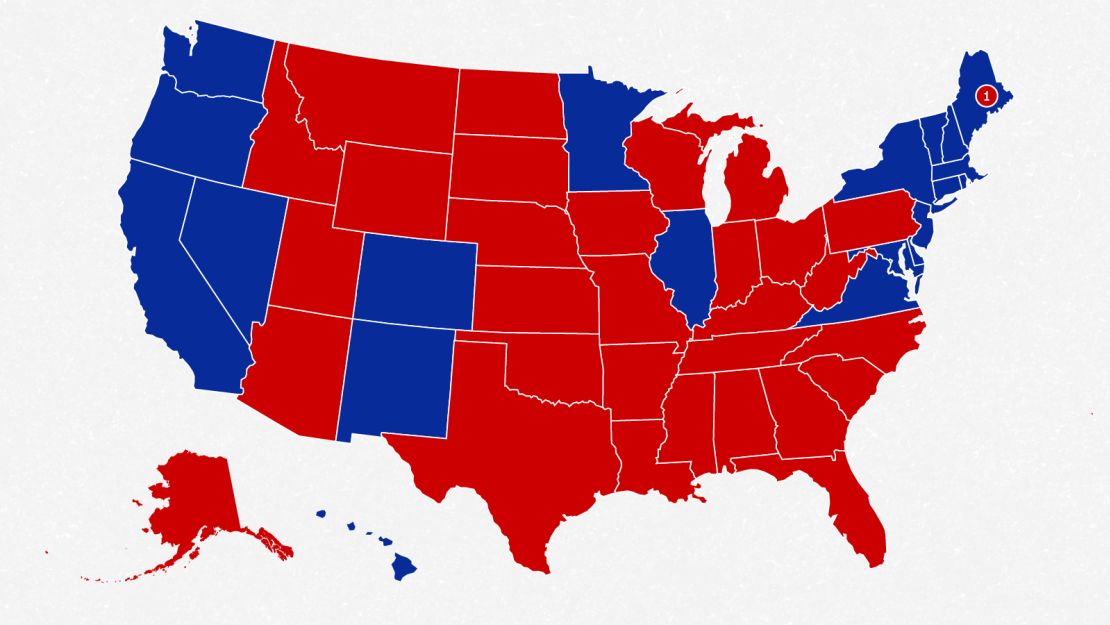

A revealing new Brookings Institution study shows that the thriving metropolitan areas at the vanguard of the transition to the highly digital, post-industrial economy flocked toward Hillary Clinton in last fall’s presidential election, while Donald Trump dominated the places largely left behind in that shift.

Clinton won preponderant majorities in the communities where the highest share of workers perform jobs that require intensive use of computerized technology – most of them larger cities, many along the two coasts. Trump overwhelmed her in the mostly smaller interior places that haven’t attracted nearly as many well-paying, information-savvy jobs, according to figures provided by the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program.

Based on Brookings’ data, CNN has analyzed the election results for all 536 federal statistical areas, including the 382 metropolitan areas, and the 154 non-metropolitan areas, which comprise all of the remaining counties not encompassed in any of the metros.

Clinton won 18 of the 20 metropolitan areas where the largest share of employees work in jobs that require high levels of digital skill, and 36 of the top 50. But Trump won a steadily increasing share of communities that ranked lower in the share of high-digital employment. He carried five times as many communities as Clinton did among the areas that ranked outside the top 200 for high-digital jobs.

“The ones at the top are … profiting from the current [economic] order of the successful internationalist, cosmopolitan, export-oriented, high-tech metropolitan centers,” says Mark Muro, the Metropolitan Policy Program’s director of policy and a co-author with three colleagues of the new study. “The other places see these changes as more a challenge and certainly a force of pain and transition, and some of them feel they have been losers in the face of this technology.”

Transformation vs. restoration

This stark economic pattern reinforces the central cultural and demographic fault lines already separating the parties. In elections from Congress to the White House, Democrats are consistently drawing the most support from what I’ve called the coalition of transformation: the heavily urbanized alignment of minorities, the millennial generation and white-collar whites generally most optimistic about the changes remaking America’s demography, culture and economy. Meanwhile, Republicans are amassing commanding majorities among the blue-collar, older, evangelical and non-urban whites generally most uneasy about all of those changes – what I’ve termed the coalition of restoration.

The challenge for Democrats is that, as the opportunities ignited by the digital revolution concentrate in fewer “superstar cities” like San Francisco, Seattle and Boston, more places feel excluded than included in this economic transformation. The challenge for Republicans, particularly in the Trump era, is that the party’s agenda is increasingly isolating it from the growing, racially diverse, post-industrial and globally integrated communities that have emerged as the nation’s most dynamic engines of economic expansion and innovation. In essence, the GOP is trading a stronger hand in the communities that are losing ground economically for a weaker one in those that are propelling the nation’s growth – an exchange that rarely proved sustainable for political parties in the past.

Participation in the computer and communications revolution that is upending the economy largely follows the borderline between the competing political coalitions. It both parallels and reinforces the class inversion that has seen Republicans gain ground among working-class whites since the 1960s, while Democrats have grown more competitive among whites holding four-year college degrees or more.

The Brookings study creatively uses a long-standing federal survey called the Occupation Information Network that provides detailed data on Americans’ experiences at work. From that data, the study tracked how heavily workers in 545 occupations (covering 90% of the workforce) use computerized technology of all sorts on the job.

A changing workforce

With those results, the study broke the workforce into three categories: those whose jobs required high levels of digital skill (professions such as software developers and financial managers), medium levels (ranging from lawyers to automotive service technicians) and low levels (security guards and construction workers.)

From 2002 to 2016, the study found, the share of all jobs requiring the highest level of digital skill soared from about one-in-20 to nearly one-in-four, while the share requiring medium digital skills increased from about four-in-10 to nearly half. With digital demands infusing so many jobs, the study found that since 2002 virtually all of the nation’s metropolitan areas have seen an increase in the overall level of digital skill in their local employment.

But, more important, the study found that the jobs that require the highest level of digital skill, and that generally also pay the most, are concentrating in fewer places. The communities that had generated the most highly digital jobs around 2000 – places such as San Jose, Washington, Austin, Boston, Raleigh, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Seattle and Madison, Wisconsin – have added them much faster in the years since than the places with the smallest share of such jobs then, such as Riverside and Fresno, California, or Youngstown, Ohio.

That separation is fueling economic polarization, because the jobs that require high levels of digital expertise now pay far more ($73,000 annually) than those that require only medium ($48,000 annually) or low ($30,000 annually) skills. What’s more, since 2010, average annual wages for high-skill digital jobs have increased over twice as fast as those for the medium-skill jobs – while wages at the lower end have actually declined by 0.2% annually. The result is that the metropolitan areas with the highest share of digital skills also now rank the highest in wages and wage growth – and are pulling farther away from those lagging in the digital transition.

These centers of digital innovation are driving an increasing share of the nation’s economic output. Since 2002, the 25 metropolitan areas with the greatest share of high-digital jobs have increased their share of the nation’s total economic output from 24% to 34%, and their share of total employment from slightly less than 21% to over 28%.

“Though there is stress, the places in the vanguard are succeeding,” says Muro. “Their problems are those of growth, rather than its absence, and they are confident in their futures.”

And those are precisely the places where Democrats now run best.

Where Clinton won

In the 20 metropolitan areas that ranked the highest in jobs requiring top levels of digital skills, those jobs account for at least 27% of all employment, Brookings found. In that top 20, the only two that Clinton didn’t win were somewhat anomalous: Huntsville, Alabama (where a large NASA installation is located) and Lexington Park, Maryland (which includes a naval base). The remaining areas in the top 20 that she carried represented the who’s who of New Economy superstars including San Jose and San Francisco in California; Denver and Boulder in Colorado; Raleigh and Durham in North Carolina; and Seattle, Austin, Washington, DC, and Boston.

Clinton also won 18 of the next 30 metros that ranked best for high-digital employment, all places where such jobs accounted for about one-fourth of the total. That list included university towns such as Madison, Wisconsin; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Corvallis, Oregon; and Columbus, Ohio, as well as such big urban centers as New York, Los Angeles, Atlanta and San Diego. Trump won 11 of these (including Bloomington, Boise and Tampa) and they tied in one.

Muro said the cities with the greatest digital opportunities – particularly those on the very top of the list – share several characteristics that now also overlap with a tendency to support Democrats. “They have high college-degree attainment; they often are coastal; they have proven to be attractive to millennials,” he said. “They have high amenities and had initially high levels of earlier [generations] of information technology activity, so they became centers of wave after wave of subsequent technologies. So it’s very much a case of the technological rich getting richer.”

Trump’s message resonated in less digital areas

The needle tilts increasingly toward Trump in communities where the digital revolution hasn’t advanced as far. In the next 50 metro areas, high-digital jobs accounted for 22-24% of total employment. Among those, Trump won 26, compared with 22 for Clinton and two ties. On this list, Clinton generally won the largest places, including Philadelphia, Miami, Chicago and San Antonio, while Trump’s strength emerges in midsized and smaller metropolitan areas ranging from Indianapolis, Nashville and Dayton to Charleston, West Virginia, and Peoria, Illinois.

Lower down, the balance shifts lopsidedly to Trump. High digital jobs accounted for between 19-21% of the employment in the next 100 communities; Trump won 69 of them and Clinton just 29 (with two ties). Trump’s wins in this category included places like Greenville, South Carolina; Midland, Texas; Fargo, North Dakota; and Green Bay, Wisconsin.

After that, as the list shifts toward smaller places rooted in manufacturing, resource extraction or agriculture, Trump dominated. High-digital jobs accounted for 18% or less of employment in the remaining 336 metro and non-metropolitan areas: Trump won 279 of them and Clinton just 55 (with two more ties). These included such blue-collar Trump strongholds as Youngstown, Ohio; Erie, Pennsylvania; and Roanoke, Virginia.

Many aspects of Trump’s agenda – such as his calls to reduce legal immigration and his retreat from free trade deals like the Trans Pacific Partnership – elevate the priorities of the less digital places over those driving the transition. That tilt is also clearly evident in the GOP tax plan moving through Congress, which would increase taxes on graduate students and homeowners in the most expensive real estate markets, particularly in blue states – a list that largely overlaps with the digital high achievers.

These economic positions reinforce the distance between the GOP and these places, particularly in the Trump era, over cultural and racially tinged issues. As the digital revolution proceeds, that could increasingly place Republicans in the same difficult position as Democrats were in the second half of the 19th century, when the party championed the agrarian South and West against the rapidly industrializing North and Midwest,, which had emerged as the powerful piston of economic growth. Behind that alignment of economic and political forces the GOP held the White House for all but eight of the 52 years from 1860 to 1912.

America is now so closely divided between the parties that such an extended imbalance isn’t likely to occur again. But with the same communities now either experiencing – or being excluded from – not only demographic and cultural but also economic change, the nation appears locked into an era of sustained political turbulence that pits what America has been against what it is becoming.