Story highlights

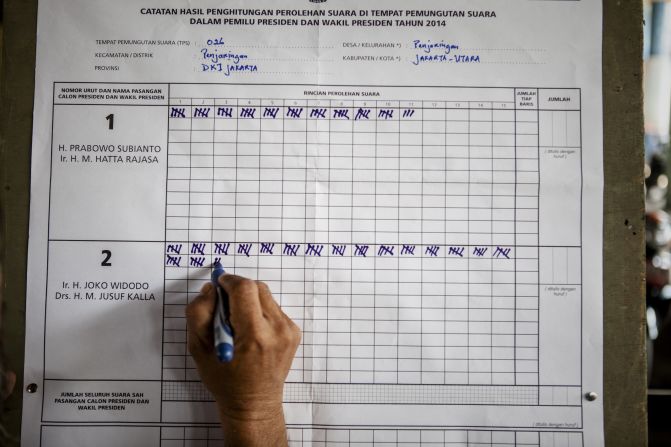

Indonesia's voters to choose between military man or self-made furniture salesman

Joko Widodo has drawn comparisons to Obama for his image as an outsider seeking to reform

Prabowo Subianto touts his military record, which has been a strength and weakness

The two men vying to lead Indonesia is a study in contrasts: a self-made furniture salesman who has sprang into contention for the country’s top political job, and a former general with a long military history who projects a strongman image.

In the fourth election for the young Indonesian democracy, Joko Widodo and Prabowo Subianto are in contention to lead a country with a slowed economy and rising voter concerns about corruption in government.

One of them will become the head of the most populous Muslim nation for the next five years when voters make their choice on July 9.

Joko “Jokowi” Widodo

Commonly known by his nickname “Jokowi,” Widodo, 53, has been compared to the 2008 vintage of Barack Obama in part for his charisma and focus on change, and also because he represents a break from the political establishment.

Styling himself as a man of the people, Widodo eschews business suits for checkered shirts with his sleeves rolled up.

As a self-made businessman turned Jakarta governor, Widodo would be the first president without a connection to the military or the country’s traditional elite.

“In order to resolve problems in Indonesia related to rule of law and fighting corruption, it can only be done by a new figure, not by someone who’s been taken hostage by the past,” Widodo told CNN.

Much like Obama’s sprightly first campaign, Widodo relies heavily on his personal history and his image as an outsider. That appeal helped Widodo charge ahead in opinion polls earlier this year, when he appeared to be a virtual lock for the presidency.

But much of his lead has eroded following smear campaigns suggesting that he is of Chinese descent or even a Christian – a deal breaker for many in this Muslim-majority nation.

The attacks have sidetracked his campaign and prompted Widodo to release evidence of his upbringing and photos of his haj pilgrimages to Mecca.

The smear campaigns have “forced Jokowi on the defensive on issues of his personal identity,” instead of being able to put up a progressive vision for the country, said Douglas Ramage, an analyst with Bower Group Asia, based in Jakarta.

Born in the central Java city of Surakarta, Widodo grew up in a slum on the banks of the Anyar River. His family lived in illegally-built shacks, in which they were evicted by the government.

This background has helped his appeal among the country’s poor.

“Jokowi is very popular among farmers and the common people,” said Hamdi Muluk, a professor at Indonesia University who specializes in political psychology. “His image is that he is part of the people.”

Widodo worked in his family’s furniture business before starting his own export company, which he made a huge success.

In 2005, he was elected mayor of Surakarta and became known for his spontaneous visits to slums, which drew media attention, and unannounced drop-ins at government offices to catch under-performing workers.

He rose to become Jakarta governor in 2012, where he piloted new healthcare and education programs. But critics say Widodo is too inexperienced and hasn’t finished his work in Jakarta after only 18 months in the governor’s office. Several major projects, including a new railway, remain behind schedule.

Widodo’s policy platform tends to be grounded by his own experience as a businessman. He speaks on the campaign trail about the difficulty of licensing and regulations, and the need to simplify the bureaucracy to help businesses succeed.

Widodo says to help Indonesia’s economy, the government has to tackle corruption.

“We will issue a decree related to strengthening a bureaucracy that is clean and always there to serve,” he said. “This way, we can attract more investment to Indonesia and consequently create more jobs.”

Prabowo Subianto

Prabowo Subianto has framed himself as the strong, decisive leader, calling for more nationalistic policies.

In a nod to both his military background and his Muslim faith, Prabowo styles himself in a khaki military-style shirt and fez, much like his former father-in-law, Suharto, the country’s second president.

A hulking presence, Prabowo even arrived to campaign events mounted on a Lusitano horse – a famed breed used in dressage.

“He’s the most experienced presidential candidate in Southeast Asia,” said Ramage. “He’s been doing this for at least a decade.” Prabowo ran for president in 2004 and for vice-president in 2009.

He has never held public office.

As leader of the Great Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) party, he has touted his military service and projected the image of a decisive man capable of taking charge.

Most voters “have aspirations for a strong leader who will turn Indonesia to have a stronger position in Asia,” said Wijayanto Samirin, managing director of Paramadina Public Policy Institute, a Jakarta think tank.

Very much part of the country’s traditional establishment, Prabowo, 62, is the son of the nation’s leading economist. He also became part of one of the most influential families when he married Suharto’s daughter, Siti Hediyati Hari in 1983. They have since divorced, but his ex-wife backs his candidacy, even appearing publicly in his campaign events.

Suharto, who passed away in 2008, led a dictatorship in Indonesia for 32 years, which was marred by allegations of corruption, repression and the politically-motivated killings of an estimated 500,000 to a million opponents and dissidents. His downfall in 1998 ushered in an era of democracy in Indonesia.

Prabowo’s military service during the time of Suharto’s reign has cast doubts over his human rights record, having served in controversial campaigns in West Papua and East Timor, which have both had independence movements, with East Timor achieving nationhood in 2002.

Prabowo, however, has played up his military record – he became a lieutenant general in the army – which has proven to be both a blessing and a curse for his campaign.

He is accused of several human rights violations, including the kidnapping of activists during the 1998 mass protests that led to Suharto’s downfall. Prabowo has denied allegations, while human rights activists say he has not been held to account for his alleged actions.

Prabowo was removed from his military post in 1998. Prabowo’s former military boss, Wiranto who supports Jokowi in the presidential race, said in a televised press conference that Prabowo had been discharged for ordering the abduction of pro-democracy activists.

In 2000, Prabowo was denied a visa to the United States, believed to stem from his human rights record. A U.S. State Department spokesman said it’s not taking a position on Indonesia’s presidential candidates but added that “we do, however, take seriously allegations of human rights abuses, and urge the Indonesian government to fully investigate the claims.”

The spokesman declined to comment about whether Prabowo’s visa denial would be reversed if he were to be elected.

When asked about the U.S. visa issue by Al Jazeera, he replied, “Nelson Mandela was blacklisted from the United States at one time. Am I not in good company?”

Prabowo’s representatives did not get back to CNN regarding an interview request by the time of publication.

Regarding the allegations, Prabowo has maintained that he was following orders. “I am the staunchest human rights defender in this country,” he said during a televised debate in early June.

CNN’s Kathy Quiano contributed to this report from Jakarta.