Follow us at @WorldSportCNN and like us on Facebook

Story highlights

Each shoe is bespoke: top farriers custom-fit horses with their own, unique footwear

Competition for jobs is fierce as farriers master both the forge and the foot

Top farriers meet at the Calgary Stampede each year to contest the world title

Work with champion horses at the Olympic Games is on offer for the best

If you want new soccer boots, the choice – and cost – can be dizzying.

Forget trawling through hundreds of new models from dozens of stores and websites. How about if someone armed with all of that knowledge turned up at your house to help you out?

Not only that, what if they took a look at your feet, picked out the best boot for you, then carefully shaped your ideal boot into an exact anatomical match?

That would be nice. But you probably won’t get that luxury treatment unless you either become a world-leading soccer player … or a horse.

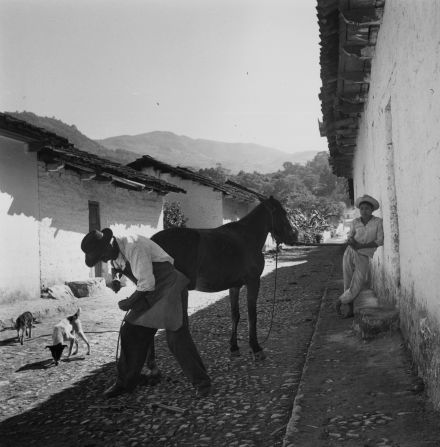

For horses, it is standard procedure for a “farrier” to shape their perfect shoe.

“Think about an old-fashioned blacksmith,” says Haydn Price, farrier to Britain’s Olympic champion showjumping and dressage teams.

“Everybody knows what a blacksmith does, but not many people know what a farrier does. First and foremost, you’re a blacksmith who specializes in shoeing horses.”

Learning the trade

To become a top farrier, you have to master a wide variety of disciplines. For example, young farriers must pass a forging examination, to demonstrate they know how to safely and precisely shape metal in a fire – exactly as a blacksmith would do.

But farriers must also spend years learning the intricacies of horses’ feet and the precise demands of the work each animal does, from a working carthorse to a thoroughbred racehorse and everything in between.

“It’s a rigorous four-year training system,” says Claire Brown, who launched the Forge and Farrier website seven years ago and whose husband Nigel has been in the business for almost two decades.

“There is a lot of competition for apprenticeships – there are far more applicants than there are places. We receive applications every week, but we only take on one new apprentice every two years.”

Shoe selector

A farrier’s main aim is to select exactly the right horseshoe from the thousands of varieties available, then ensure each shoe perfectly matches the horse, often by custom-fitting each shoe.

Switching all four shoes on a horse usually takes around an hour if it’s a simple job. Under pressure – for example, at a big competition – a farrier could change one shoe in five minutes if everything went to plan.

Price says the vast number of designs available in the 21st century, just like the proliferation in soccer boot designs, has changed the nature of a farrier’s work.

“As little as 15 years ago, there were probably only six types of shoe to cover a range of common conditions and injuries,” he explains.

“Now, 99.9% of the time you are making a bespoke shoe. Every time you pick up a horse’s foot, you should be creating a specialist shoe – even if, on the face of it, you are using what appears to be a normal shoe. It’s the application of it, not the product.”

Risky business

The job is becoming increasingly popular, combining an outdoor lifestyle and hands-on work with the chance to spend your working day with animals.

But it can be a dangerous game.

“There is a real risk,” warns Brown. “There are animals that aren’t well-handled, there are young horses, there are quite highly-strung racehorses.

“If something startles them – like a bucket being blown over in the wind – and if the farrier is in the wrong place, you can get trodden on easily.”

Her husband has been kicked in the face while working. “It was only through sheer luck that the hoof-print went around his eye, not in it,” Brown says. “The print circled his nose, cheek and eyebrow.”

Other farriers have spent weeks in intensive care following kicks and falls, but most will tell you that the physical toll of the work is a bigger danger.

“This is not something you’ll want to be doing when you’re 65,” says Brown.

“A lot of farriers have back problems and, while you can earn a good salary, you can only really earn that for 20 years of your career.”

Best of British

This has not discouraged the 3,000 or so farriers currently working in the UK, which is officially the home of the best – as demonstrated at the discipline’s world championships.

The Calgary Stampede hosts this event each year, pitting farriers from across the globe against each other in judged forging and shoeing contests.

Yorkshireman Steven Beane has won five times in the past six years, taking his latest world title in early July. Since 1985 there have been only six non-British winners.

“The judges look at how accurately you can replicate a specimen shoe design, the quality of your forging, the trim – how you prepare a foot to receive a shoe – and then how well the shoe fits the foot, is nailed onto the foot and presented,” says Brown, who is organizing this year’s European championships in Lancashire.

“At this year’s world championships, there was a completely UK-based top five and that is consistently the case.”

Not everyone indulges in competitive farriery, though.

When Price first joined the British world-class program in the late 1990s, working with top riders, he realized this was the challenge he wanted: playing a small part in winning Olympic medals.

“When I came away from London 2012, on the drive home, I felt for the first time in my life as though I had actually achieved something,” says Price, who will work for the British team again at the FEI Alltech World Equestrian Games in France, starting on August 23.

Price oversaw the shoeing of horses like Charlotte Dujardin’s Valegro, who won individual and team dressage gold, as well as the four British horses who rode to the team showjumping title.

“It’s not the event that’s difficult,” says Price. “It’s the pressure leading up to it. Horses have an unbelievable desire to break themselves and the pressure before the event can be quite something.

“When everything goes right, the first emotion is relief. When I knew we’d won the gold medal at London 2012 I broke down, and I’m not afraid to admit it.

“For the first time in my life, I understood – when you watch grown men crying on television when they get out of rowing boats or at the athletics – I understood where that comes from.”

The farrier’s challenge

Price spends roughly a quarter of each year working with top British horses, driving around 28,000 miles in the process.

From the age of 14, farriery has gripped him. While the spotlight fell on the riders at London 2012, finding and fitting the perfect shoes for home Olympic gold marked the culmination of his life’s work.

“I don’t do farriery competitions anymore,” he says. “My competition is a self-imposed one: maintaining these horses to their peak performance.

“Competitions are hugely skilful and I take nothing away from them, but you are judged on a moment in time.

“I’m judged by the work that I do on a continued basis, to keep horses sound and fit, year after year after year. That, for me, is the farrier’s challenge.”

Read: Guide to equestrian disciplines

Read: Girl with the dancing horse no longer fears last waltz