Story highlights

A group of doctors from Argentina claims that a pesticide could be the cause of an outbreak of microcephaly in neighboring Brazil

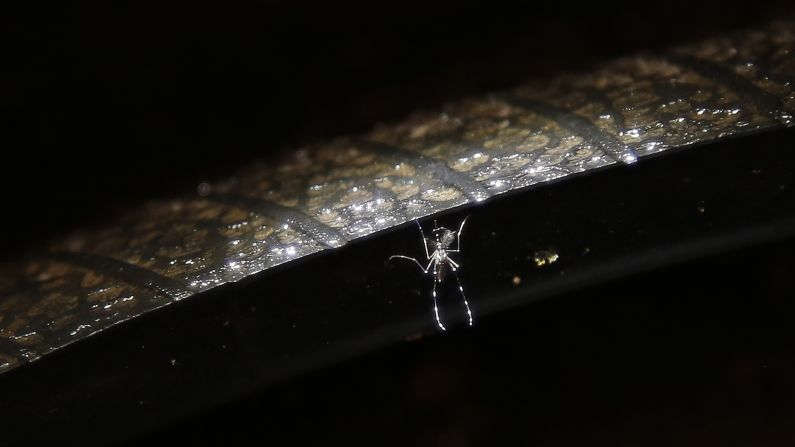

The pesticide, Pyriproxyfen, is used to eliminate mosquito larvae

Brazil's federal government and WHO reject the claim and say the likely culprit is the Zika virus

Brazilian health officials and the World Health Organization are denying links between a well-known pesticide and microcephaly, a condition that causes babies to develop abnormally small heads and leads to death in some cases.

The pesticide is called Pyriproxyfen, and it’s used in water tanks to eliminate mosquito larvae.

A group of doctors from Argentina claims this larvicide could be behind the recent surge in babies born with microcephaly in Brazil. Based on this claim, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil’s southernmost state, has decided to ban the larvicide.

The mosquitoes that changed history

Joao Gabbardo dos Reis, secretary of health for Rio Grande do Sul, announced Saturday that the use of the larvicide to treat water used for human consumption is now prohibited.

“We decided to suspend the use of the product [Pyriproxyfen] in human consumption water until we get a position in the Ministry of Health and because of that we strengthen the appeal to the population to eliminate any possible breeding ground of the mosquito,” said Gabbardo said.

Argentinian group: Zika being blamed too quickly

The Brazilian state made its decision based on a report published by the University Network of the Environment and Health, a group of doctors from Argentina.

Among other things, the report criticizes the Brazilian Ministry of Health for quickly trying to link Zika to microcephaly.

“They fail to recognize,” the report says, “that in the area where most sick persons live, a chemical larvicide producing malformations in mosquitoes has been applied for 18 months, and that this poison (Pyriproxyfen) is applied by the state on drinking water used by the affected population.”

The pesticide is manufactured by Sumitomo Chemical. The Japanese company says it has distributed its product for the past 20 years to about 40 countries, including Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Denmark, France, Greece, the Netherlands and Spain.

Highlights from Facebook chat with CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta

It also distributes Pyriproxyfen in Latin American countries such as the Dominican Republic and Colombia.

In a statement, the company denies any link to abnormalities in babies saying that the product “[…] is safe and effective for the use in combating diseases spread by mosquitoes, and that the concerns related to microcephaly are totally unfounded.”

Brazilian government and WHO back company

Brazil’s federal government and the World Health Organization are siding with Sumitomo, saying that there is no scientific evidence linking Pyriproxyfen to microcephaly and disagree with Rio Grande do Sul’s authorities about the need to impose a ban.

The Brazilian Health Ministry says that “there is no epidemiological studies showing the association between the use of Pyriproxyfen and microcephaly.”

In a statement, the ministry also says that “unlike the relationship between the Zika virus and microcephaly, which has had its confirmation attested in tests that indicated the presence of the virus in samples of blood, tissue and amniotic fluid, the association between the use of Pyriproxyfen and microcephaly has no scientific basis.

Join the conversation

“Importantly, some localities that do not use Pyriproxyfen were also reported cases of microcephaly.”

Pyriproxyfen is one of 12 larvicides that the WHO recommends to reduce mosquito populations. The WHO says the product is intended to manage insecticide-resistant mosquitoes and has been used since the late 1990s.

Regarding Brazil, the WHO told CNN that “after additional reviewing toxicology data on Pyriproxyfen, WHO has concluded that there is no evidence that would suggest that the larvicide could be the cause of the current outbreak of microcephaly in northeastern Brazil or the one that struck French Polynesia in 2013-2014.”

What threat does Zika pose to the Rio Olympics?

The agency also notes that in animal studies, the larvicide leaves the system within 48 hours through urine and they have no found any impact on offspring.

Additionally, officials in the Brazilian city of Recife, considered ground zero for transmission of the Zika virus and cases of microcephaly, say that it has never used the pesticide to combat Aedes Aegypti, the mosquito that carries the virus. Recife is a coastal city in the eastern most point of South America.

While experts have been clear that there is not scientific proof the Zika virus causes microcephaly, the evidence is becoming stronger.

The Catholic University of Paraná in southern Brazil announced Tuesday that researchers have found the Zika virus in tissue samples from the brains of babies born with microcephaly. The announcement bolsters similar findings.

In spite of the dismissal by Brazil’s federal government and the WHO, Gabbardo says the ban will not change, even without scientific evidence.

“The suspicion is enough to make us decide to suspend use. We cannot take that risk.”

CNN’s Debra Goldschmidt, Yoko Wakatsuki and Marilia Brocchetto contributed to this report.