Story highlights

Thousands of children never make it as far as the United States

They are detained in Mexico and deported

Poverty, violence push them north; the journey is dangerous

Tossed in a truck, robbed. Dumped at a house. Held for ransom.

The 14-year-old traveled alone by bus from his home in Honduras, through Guatemala, into Mexico, where his dream of reaching the United States was cut short by a band of criminals.

Nehemias said his family was forced to pay $2,000 for his release. He had nowhere to go.

“I turned myself over to (Mexican) immigration authorities. I didn’t have any more money. They took all the money. They took everything I had,” he told CNN in San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

Dressed in jeans and a black T-shirt, the teen spoke softly.

“I was told (by the kidnappers) that if I ever came back, the fine would double – that it was dangerous – and I wouldn’t make it back to my home country,” he said.

While the Obama administration is focused on unaccompanied minors who make it to U.S. soil, Nehemias – one of dozens of children Mexican authorities sent back to Honduras this week – represents another, larger, problem.

‘I want to be with my mother’

Thousands of children never make it as far as the United States.

This year alone, 4,500 unaccompanied minors from Honduras have already been detained in Mexico and deported, according to the Honduran Institute for Children and Families, or IHNFA.

They end up here, at an IHNFA facility in San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ most violent city.

The processing center is surrounded by a 6- or 7-foot cinder block fence topped with rings of barbed wire.

The children arrive by bus and, once inside, wait for family members to claim them. Only legal guardians with proper documentation can cross the fort-like fence and walk out with a child.

Unclaimed children stay in on-site dorms until a family member can be reached. The beds are simple; the ceiling is open. There is no air conditioning, but at least it’s safe.

“I want to be with my mother. I haven’t seen her in eight years,” said Francy, a 15-year-old girl, who cried as she spoke about her trek north.

She made it as far as Veracruz, Mexico, and was about to hop on the final bus ride to the U.S. border when she was detained by Mexican immigration authorities. They sent her back to Honduras.

“I was scared because as a woman traveling alone, I didn’t know the intentions of the men in the group,” she said.

CNN is not publishing her last name, nor that of Nehemias, because they are underage.

Francy says her mother, who lives in Memphis, Tennessee, had paid someone $3,000 to take her across the border.

“We are told to say we are traveling alone,” she said. And if Mexican officials asked for documentation, Francy was supposed to bribe them with pesos.

Her trip ended, she says, when the bribe fell short.

‘I don’t want to go back’

Why are so many children risking their lives to move to the United States?

A recent United Nations report that interviewed 400 young immigrants points to a difficult and complicated web of reasons, including violence, poverty and the desire to reunite with their parents or other family members.

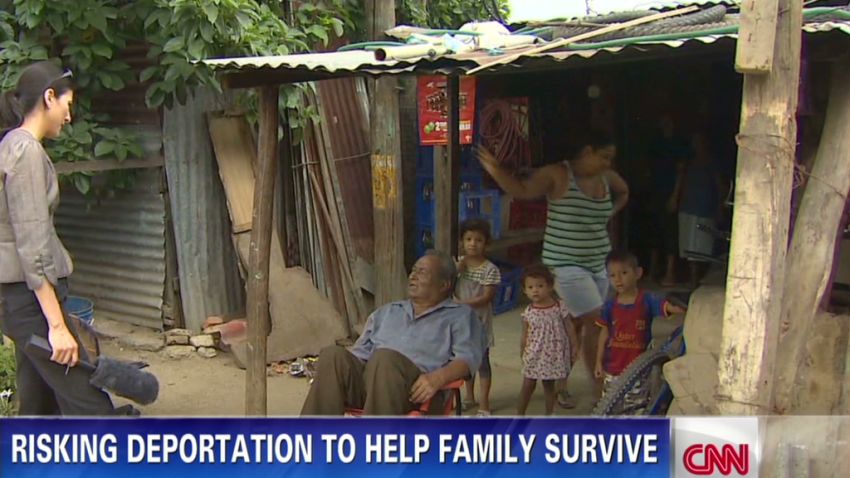

“We are trapped because of the thuggery in our communities,” said Natalia Lopez Manuelez, who lives in Las Brisas, a neighborhood in San Pedro Sula.

She said her community of about 3,000 residents was constantly raided by gangs looking to assault, rob and kill. Her neighbors described horrific tales of of men stripping homeowners of everything they owned and even killing for the thrill of it.

“If you were held at gunpoint and you didn’t give up everything you owned, they would kill you,” said security guard Mario Aquino Vasquez.

Las Brisas residents got so fed up with the violence they created a neighborhood watch group and built gates. Today, armed guards stand at the entrance, blocking people who don’t live there from getting in.

“Little by little we cleaned up the neighborhood,” said Vasquez. But poverty remains.

Dirt roads connect homes that are patched with corrugated iron. Many of the houses have no windows or doors. The residents are part of the more than half of Hondurans who live in poverty.

It was that lack of opportunity that Nehemias was trying to escape. He wanted a better life, but said he won’t try again.

“I don’t want to go back.” the teen said. “I want to stay in my country and leave the rest to God.”

Inside San Pedro Sula, the ‘murder capital’ of the world

Daniel’s journey: How thousands of children are creating a crisis