A former British soldier will stand trial for firing on civil rights protesters in Northern Ireland in 1972, an event that came to be known as Bloody Sunday, prosecutors said. But 16 other ex-paratroopers and and two former members of the Official IRA will face no action.

The army veteran, known as Soldier F, has been charged with the murder of demonstrators James Wray and William McKinney and the attempted murders of four other men, the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland said Thursday.

Bloody Sunday was one of the darkest episodes in Northern Ireland’s Troubles. On 30 January 1972 troops fired on unarmed protesters in a civil rights march in Derry, also known as Londonderry, killing 13 people and wounding 15. One injured man died four months later.

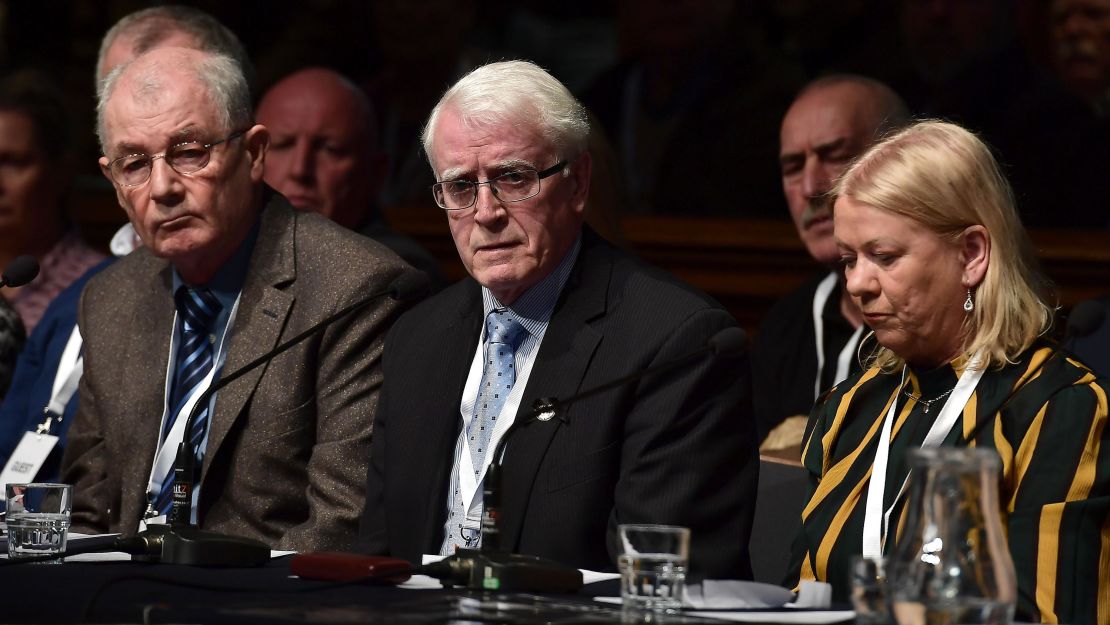

The families of the victims have campaigned for decades for the former soldiers to face justice. Relatives were visibly upset following the announcement of the decision.

Solicitor Ciaran Shiels, a solicitor for a number of them, said they were “disappointed that not all of those responsible are to face trial.”

John Kelly, whose brother Michael was killed on Bloody Sunday at the age of 17, told the UK’s Press Association (PA) news agency that the verdict was a “terrible disappointment” but he was glad Soldier F will be prosecuted.

Kelly added that it is legally possible for the families to challenge the decision not to prosecute the other former soldiers.

“We have walked a long journey since our fathers and brothers were brutally slaughtered on the streets of Derry on Bloody Sunday, over that passage of time all the parents of the deceased have died – we are here to take their place,” he said, reported PA.

“The Bloody Sunday families are not finished yet.”

However former soldier Alan Barry, founder of the Justice for Northern Ireland Veterans group, also expressed disappointment, according to PA.

“It’s one soldier too many as far as we’re concerned,” said Barry. “It happened 47 years ago, a line in the sand needs to be drawn and people need to move on.”

Game-changer in Northern Ireland

The march had been banned by Northern Ireland’s police and the British Army, but organizers wanted a peaceful demonstration, avoiding confrontation at the barricades with the well-armed soldiers.

Journalist and author Eamonn McCann, one of the march’s organizers, remembers bullets flying, being forced to hide in the gutter and crawling away to escape.

Although rioting had become routine for Derry’s youth, McCann describes the impact of Bloody Sunday as a game-changer in Northern Ireland. And it transformed Catholic opinion at the time.

“The innocence was gone; also the possibility of a reformist … solution to what was going on in Northern Ireland was, if not destroyed, substantially diminished by Bloody Sunday,” McCann said.

The impact of the killings was an immediate accelerant for the violence that would claim 3,500 lives in the 25 years to the Good Friday peace agreement in 1998, McCann said.

The victims’ families were stunned by the events of the day, not just at the loss of their loved ones but by the army’s claims that the people in the crowds fired the first shot.

The soldiers maintained they were acting under order, returning fire on what they believed to be hostile armed attackers.

A short internal military inquiry shortly after Bloody Sunday, known as the Widgery Report, concluded the soldiers had done nothing wrong. And for many years that was the accepted government narrative.

Saville Inquiry

Over time, though, the victims’ families got organized, campaigned for justice and eventually, more than 25 years after the killings, when a peace deal was signed in Northern Ireland, the British government committed to a full-scale inquiry.

Headed by Lord Saville, the inquiry lasted 12 years, with 435 days of oral evidence alone. It involved more than 2,000 witnesses, with an estimated 125,000 pages of evidential material considered.

It cost a quarter of a billion dollars and its conclusions, announced by British Prime Minister David Cameron in 2010, brought cheers from the people of Derry, in particular the victims’ families.