A recent crackdown on women’s rights activists in Saudi Arabia has cast doubt over a much-touted reform agenda led by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

At least 11 women’s rights activists have been arrested in recent weeks, according to rights groups, and are believed to be faced with counterterror charges punishable by up to 20 years in prison.

The State Security Presidency, a powerful security apparatus that reports directly to the King and 32-year-old Crown Prince, had been monitoring the detainees prior to their arrest, according to Saudi Arabia’s official news agency.

At least four of the detainees have been released in recent days, according to Amnesty International.

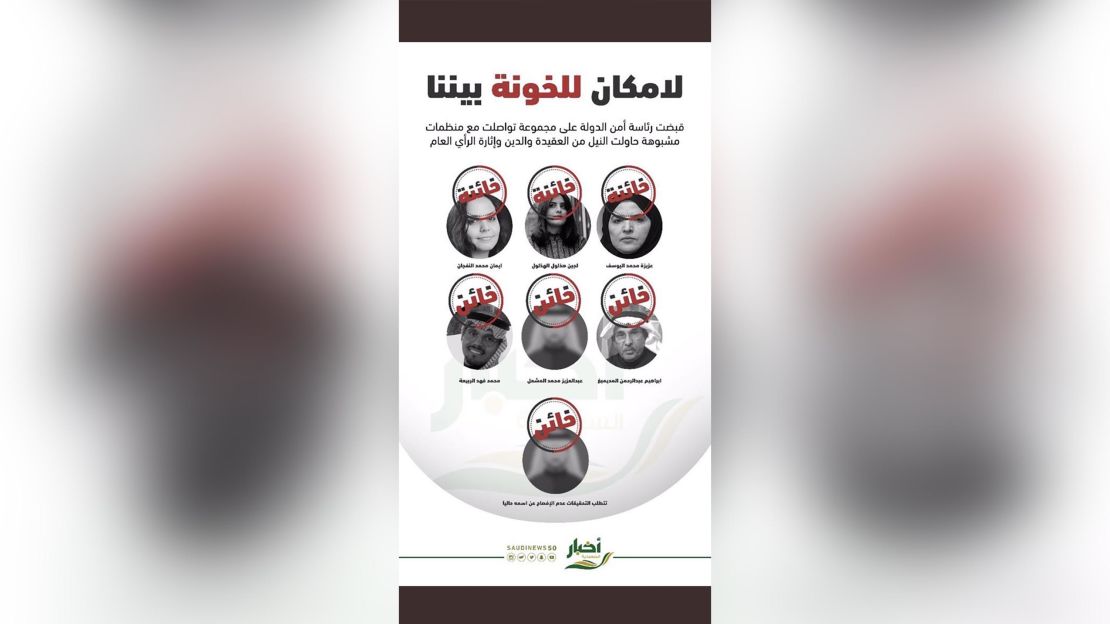

But while the arrests were lauded in Saudi Arabia’s mainstream press – government-aligned media branded the activists “traitors” – international groups and pundits, some close to the Saudi government, said the move was difficult to defend.

One Saudi activist who previously supported the Crown Prince’s ambitious reform agenda said he has felt disillusioned by him in recent weeks, canceling plans to return to the kingdom.

Others staunchly opposed to the Crown Prince have said that the crackdown has “exposed the myth” of the reform agenda.

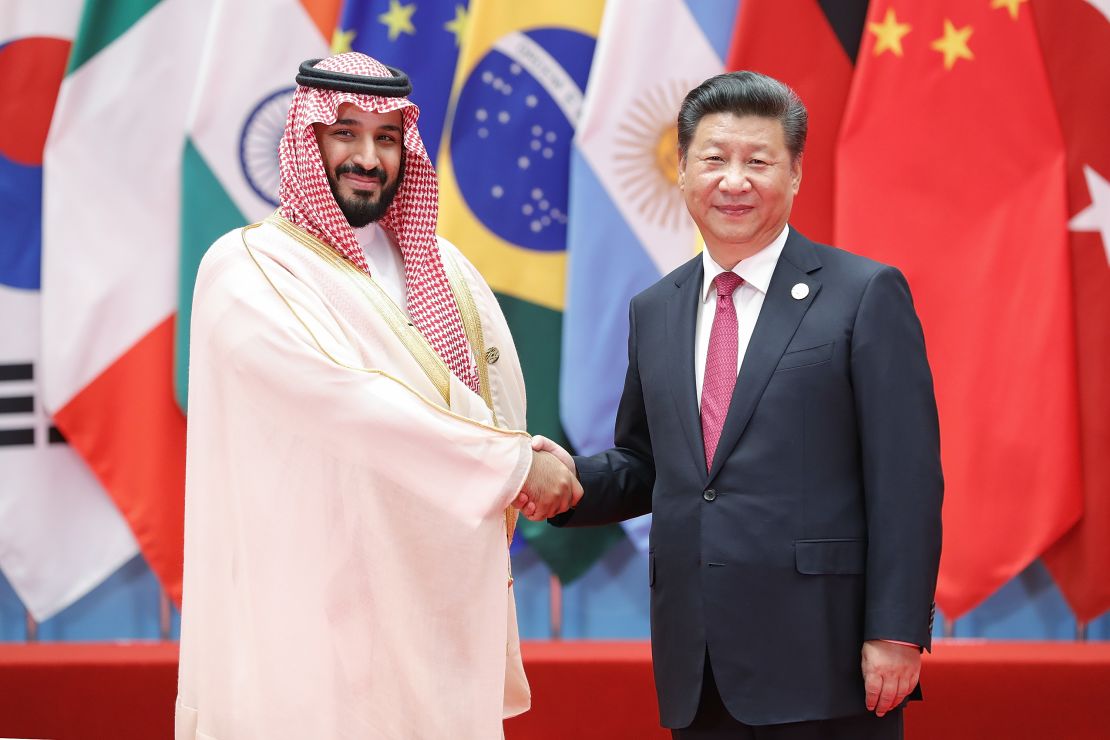

The arrests come on the heels of Mohammed bin Salman’s month-long tour of Western countries, where he was billed as a modernizer spearheading change in the ultra-conservative kingdom.

They also come in the run-up to June 24, when Saudi Arabia is set to lift a notorious ban on female drivers. Many of those arrested are high-profile campaigners against the law which barred women from getting behind the wheel, leading analysts to question why the young Crown Prince would go after activists who seemingly share his reformist goals.

Not enough change

Prior to bin Salman’s rapid rise to power in recent years, Saudi Arabia’s largely fundamentalist clergy held considerable sway over policy-making in the kingdom. The arrest of some prominent clerics in recent months, in addition to a series of moves that consolidated the Crown Prince’s grip on decision-making, helped to clip the clergy’s influence.

Over the past year, Saudi Arabia opened its first cinema in decades and loosened several morality laws that discriminate against women, including its notorious rules requiring that women receive a male guardian’s permission to travel, receive an education, and sometimes work and receive healthcare.

But those familiar with the detained activists, many of whom were part of global campaigns against the male guardianship laws, say that they wanted more reforms. They say that the activists feared that changes would stop if they did not continue to work for greater rights.

“Women are given the right to drive (by Mohammed bin Salman), thinking this would be the end of the journey,” said Madawi al-Rasheed, a Saudi visiting professor at the London School of Economics.

“But I think those women believe that the journey has just begun because the ceiling is very high and they’re not going to stop at the prospect of driving a Jeep in Saudi Arabia. They have demands that need to be honored,” she added.

One of the most high-profile activists arrested in recent months, Loujain Al-Hathloul, was previously detained for 73 days in 2014 after trying to drive from the United Arab Emirates to Saudi Arabia. Another detained activist, Aziza al-Yousef, 70, is one of the country’s earliest activists for the right to drive and signed a petition in recent years calling for an end to guardianship laws.

Eman al-Nafjan, a third detainee, is a well-known blogger who drove in Riyadh in 2013 as part of a protest that attracted international attention.

“Those arrested – Loujain, Aziza, Eman, and the others – all agree with social changes underway in the Kingdom,” read a report by the Washington, DC-based Project on Middle East Democracy.

“But they have not been content with them, believing that Saudi women still face structural discrimination and other disadvantages under present laws.”

Shortly after Saudi Arabia announced that the driving ban would be lifted, the government told activists currently detained to stop speaking to the media, activists and analysts familiar with the case said.

“Those who were targeted (in the arrests) were banned from any kind of public activity after warnings that authorities gave to them. Some of them closed their social media accounts. So why is this happening now?” well-known Saudi activist and Harvard University fellow Hala Aldosari wrote in a tweet.

Imminent lifting of the driving ban

The timing of the arrests, Mohammed bin Salman’s defenders and detractors argue, is key.

When women are finally allowed to drive on June 24, the Crown Prince wants to reiterate that the change was directed only by Saudi authorities, analysts say.

Activists, who are regularly accused by Saudi Arabia’s conservatives of being Western-backed, would be pushed out of the frame.

“(The activists) can’t be seen as taking credit for the right to drive. Firstly, it would be taking credit away from the Crown Prince and also would give the impression that activism pays off,” said Kristian Ulrichsen, Rice University Baker Institute fellow for the Middle East.

“The Crown Prince doesn’t want to give that impression, that people can agitate for change and get results.”

The crackdown, one Saudi analyst argues, pays “lip service” to the kingdom’s conservatives, and helps the young prince achieve a “balancing act” in a domestic minefield of Islamists, business tycoons, modernizers and a swelling youth population.

“If there are activists on the women’s section, there will be activists on the Islamists section and then they’ll say ‘why are you arresting clerics when these girls are doing X, Y, Z? Is it just because the Americans like them and they’re being celebrated in the West?’” said Ali Shihabi, founder of the Washington, DC-based Arabia Foundation.

“That’s the sort of balancing act that the government has to claim.”

Shihabi said that the activists were caught “on some technical breaking of the law” and that the response by authorities was trumped up because of the imminent lifting of the driving ban.

“(Mohammed bin Salman) has the 24th of June coming up, reality is going to hit people. Women are going to be on the streets driving. They don’t want demonstrations on the street. They don’t want radicals coming out and attacking cars. They want to manage it in as smooth a way as possible,” said Shihabi, adding that Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia never pretended to implement anything other than a “top-down reform process.”

Still, Shihabi said the arrests do not bode well for a kingdom that has tried to burnish its image on an international stage. “It’s very unfortunate. Everyone accuses Saudi Arabia of being so PR-savvy. If it was, it wouldn’t have done this because it’s a PR disaster,” he said.

A crackdown on civil society

Meanwhile, rights groups fear the worst for the activists arrested. Those groups have long been critical of Royal Decree 44a, which state-aligned media say the detainees have been accused of violating.

“We are very worried that these women and other activists detained, like activists before them, will be tried and sentenced on trumped up security-related charges for their peaceful human-rights activism,” said Dana Ahmed, Amnesty International’s campaigner on Saudi Arabia.

The decree makes it easy for dissidents to face terror charges punishable by three to 20 years of prison time, said Human Rights Watch in a 2014 statement.

Social freedoms may arrive in the kingdom as a steady stream but political rights remain few and far between, noted the Project on Middle East Democracy in a report this month.

“No matter how welcome the new social freedoms among many Saudis, Mohammed bin Salman’s reforms stop far short of granting rights that would remake Saudis from subjects receiving top-down directives into citizens with voices,” the report reads.

Rights groups also said that the crackdown on women’s rights campaigns, long seen as one of the activist spheres more tolerated by Saudi authorities, could foretell the end of Saudi civil society.

“It’s completely unjustified that they’re going after (women’s rights activists) one by one and in a sense they are shutting off this space for civil society, for freedom of expression and for people to demand their rights completely,” said Ahmed.

Al-Hathloul – who could face a long prison term – was complimentary about the Saudi Crown Prince in one of the last tweets she posted before her arrest, writing on March 9 that his remarks acknowledging the checkered Saudi human-rights record “are reassuring, and they reflect a clear interest in international standards.”

But she added a plea. “we can make a qualitative leap forward in improving the kingdom’s reputation and prove the seriousness of these statements by reviewing the cases of prisoners of thought.”

Her Twitter feed went dark three days later.