Researchers have been investigating the incredible cargo from an 800-year-old shipwreck for years, trying to uncover its secrets. Now, with the help of what researchers called an X-ray gun, they know more about where the beautiful ceramics found on board were made and about the ship’s route.

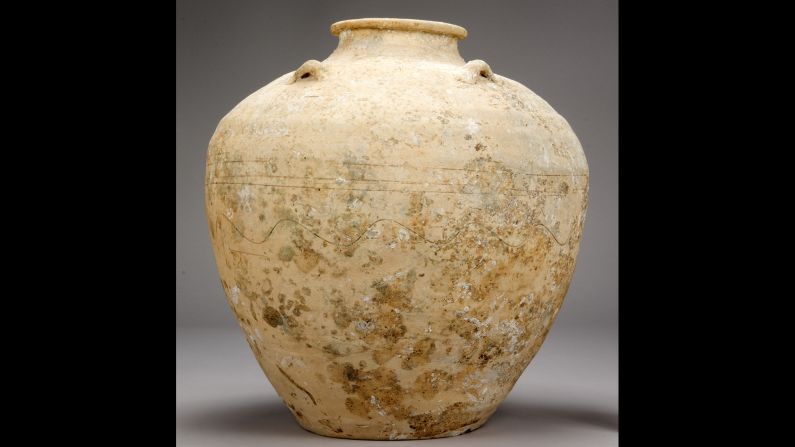

Fishermen found the wreck in the 1980s in the Java Sea, off the coast of Indonesia. A cargo including thousands of ceramic pieces, cast iron and luxury trade goods, such as elephant tusks and resin for incense, is all that remained of the wreck after the ship’s wooden hull disintegrated.

An initial study about the shipwreck and its cargo was released in June. The Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago holds about 7,500 pieces of the shipwreck’s cargo.

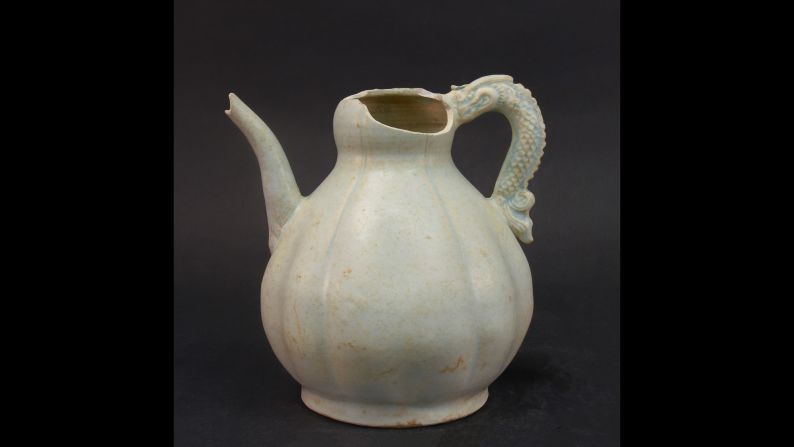

In the researchers’ latest study, published Friday in the Journal of Archaeological Science, a portable X-ray fluorescence detector was used to study 60 qingbai ceramic bowls and boxes, which get their name from the bluish-white glaze covering the porcelain. This X-ray gun allowed the researchers to determine where the cargo itself came from before it was ever loaded onto the ship.

Looking at the ceramics wasn’t enough. They were able to determine that the style itself originated in southeastern China, but there were hundreds of ancient kilns there that could have produced them.

Analyzing the chemical makeup of the ceramics would allow the researchers to determine clay from specific regions or even how the clay was mixed.

The researchers compared the chemical makeup to that of ceramic samples from ancient kiln sites in southeastern China.

“Each kiln site uses its own materials and ingredients for clay – that’s what makes each sample’s fingerprint unique,” said Wenpeng Xu, lead study author and graduate student with the anthropology program at the University of Illinois at Chicago, in a statement. “If the fingerprint of the sample matches the fingerprint of the kiln site, then it’s highly possible that that’s where the sample came from.”

Xu was able to access the Elemental Analysis Facility at the Field Museum, which includes the portable X-ray fluorescence analyzer, and study materials from the shipwreck in collaboration with Field Museum archaeologists Gary Feinman and Lisa Niziolek.

This portable detector is relatively inexpensive, fast and, even more important, non-destructive to the material it’s analyzing. It can also be taken into the field to rapidly classify objects at archaeological sites.

“It looks a lot like a ray gun,” Niziolek, Field Museum Boone research scientist and co-author of the study, said in a statement. “You’re shooting X-rays into a material you’re interested in. It excites the material’s atoms. Energy goes flying out, and this measures that energy. Different elements have different signatures of energy that comes back out.”

There were three types of ceramics in the collection that was studied. Type I was the finest, thin with a fine white paste and translucent bluish glaze. Type II’s paste was more of a sugary white paste and a grayish-white or light bluish-white glaze. And Type III’s had a grayish-white paste along with a glaze that ran from gray to green decorating plain bowls.

The researchers were able to match these with samples from kilns.

“Based on the results of this project, it is clear that the qingbai-style ceramics from the Java Sea Shipwreck came from a variety of kilns in China,” the researchers wrote in an email. “Finely made qingbai wares from Jingdezhen only account for a very small percentage of the cargo. The majority of the qingbai wares came from kilns in Fujian province, which produced a huge number of ceramics for export to markets in East and Southeast Asia and other parts of the Indian Ocean World.”

This new information actually changes part of what was published in their 2018 study.

“Previously Quanzhou, one of the largest ports in the world during the 11th-14th centuries, was thought to be the ship’s port-of-departure,” they said. “Results of this study show that a large number of ceramics in the cargo were produced at kilns in northern Fujian, which are closer to the port of Fuzhou. We now think the ship probably sailed from the Fuzhou then to Quanzhou to load porcelains from the kilns in the Quanzhou region.”

Knowing where the ceramics came from, as well as the ship’s route, sheds more light on what trade was like during this time, which was extensive and complex.

“It shows that traders and merchants relied on access to a variety of ware types of varying qualities to satisfy the diverse markets in Southeast Asia and other parts of the Indian Ocean World,” the researchers said. “It also provides evidence that potters in Fujian and Jiangxi provinces, even those working more inland, were involved in vast maritime trade networks ranging from East Asia all the way to East Africa.”

The portable detector is being used to study other cargo from the shipwreck, and even more sensitive techniques are being used to further analyze the ceramics.

Xu will continue to investigate kiln sites in Fujian as part of his dissertation research to better understand the export porcelain economy in China, and Niziolek will work with Chinese colleagues to survey kiln sites and collections in China to grow the data set.

“The ceramic analyses are part of a larger investigation to discover the sea networks that the wreck’s voyage was part of,” the researchers said. “Our team is also collaborating with colleagues at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, to conduct DNA analysis on elephant tusks that were recovered from the wreck in order to determine if they are from African or Asian elephants.”