“Love you mom and dad” read a message in purple ink on the child’s arm.

Seven-year-old Vanessa Reed wrote it this year while hiding behind a bookshelf during a lockdown at her school in Wilmington, Delaware, where she is in second grade.

The school went on lockdown after an administrator received a phone call warning of a bomb on school property. Just like she had rehearsed, Vanessa hid and kept quiet.

Thirty minutes later, authorities issued the all-clear. There was no bomb.

That night, Vanessa seemed to be coping with just fine. But as her mother, Shelley Harrison Reed, changed Vanessa out of her uniform, she noticed the chilling message in purple marker.

“Why did you write that on your arm?” Reed asked.

“In case the bad guy got to us and I got killed, you and Daddy would know that I love you,” Vanessa said. It was then that the girl began to cry.

“It was a very emotional and shocking moment for me,” Reed said. The threat “was real enough to where she thought, ‘I might not see my mom and dad again,’ which is really hard for me to say still.”

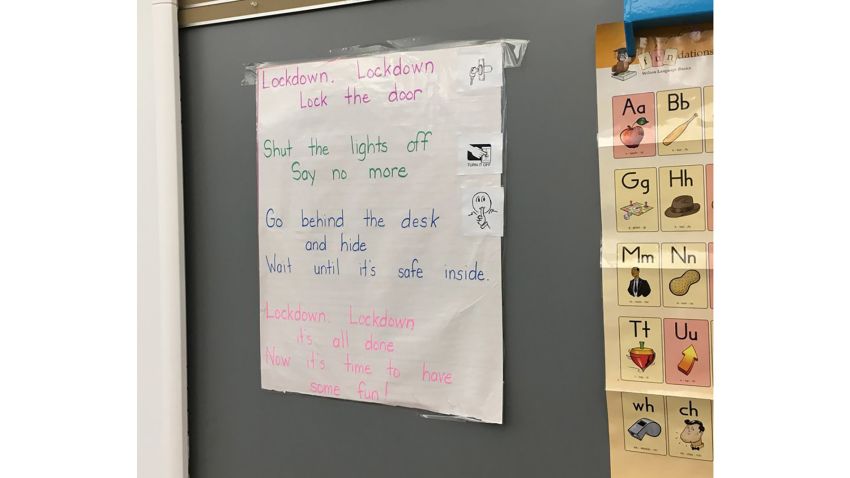

Students in several Denver-area school systems experienced lockdowns and school closings this week after credible threats from a Florida woman, authorities said. All over the country, schools regularly engage in safety drills, rehearsing what to do if there’s a real threat. Some are conducted in such realistic ways that students’ reactions are nothing short of real.

In conversations with educators, Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, has learned that many students spend more time in active-shooter drills than they do in after-school activities like school plays, she said.

And it’s not clear how effective the school safety procedures are at actually keeping children and teachers safe.

A false sense of security

A study published in March examined practices implemented in US schools from 2000 to 2018 aimed at preventing firearm violence. After examining close to 90 studies published in the peer-reviewed literature, the researchers found no evidence that the tactics – such as videocameras, bulletproof glass and classrooms that lock from the inside – actually worked; they are instead creating a false sense of security, the study authors said.

Active-shooter simulations can similarly offer false reassurance, explains Michael Dorn, executive director of Safe Havens International, a company that has assessed the safety of nearly 8,000 schools around the world.

“Training people on active shooters is actually reducing the options and types of options that people need in order to effectively address many life-threatening situations,” Dorn said: For example, teachers should receive basic training on how to approach a student who is threatening to kill themselves, especially if they are armed.

Through his work, he has also learned that overtraining can give people a false sense of confidence that could impair their decision-making in a real-life scenario, he said.

So what are the threats – and the preparation for possible threats – doing to this generation of children?

Little is known about the long-term impact

Dr. Steven Schlozman, a child psychiatrist at Harvard University and co-director of the Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds at Massachusetts General Hospital, explains that depending on how they’re conducted, lockdown drills can make children very anxious and even traumatized. The effect is worse for kids who, like Vanessa and the students in Colorado, endure real lockdowns rather than just drills.

“We don’t know whether it’s something that kids take in stride or whether this has a lasting impact that makes them less willing to take the kinds of healthy risks that we want children to take for the purposes of their development,” Schlozman said, referring to the need for children to feel safe enough to eventually do simple things like cross a street on their own.

Studying the long-term effects of lockdowns is challenging, he explains. It would be unethical to divide children into groups and subject only some to lockdowns for the purposes of understanding which children do well in the future and which don’t.

He also worries that in today’s media landscape, kids are constantly exposed to images of the very threat for which they are preparing at school, making it more real, he said.

“I think it’s becoming clear that, through well-intentioned efforts to protect our children and keep them safe, we are actually harming them emotionally,” said Dr. David Schonfeld, professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement.

Young kids may also not know the difference between reality and fiction or a faraway threat versus a close one.

Abbie Clements, an elementary school teacher in Newtown, Connecticut, who survived the 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary, says her students look to her for frequent reassurance during drills.

“I feel like I have to say [that it’s a drill] several times because they’re looking at me like, ‘are you sure? Are you sure?’ ” she said.

Ultimately, Schonfeld said, schools do what they believe to be best practice. “But we need to establish that the best practice cannot be traumatizing,” he added.

Avoiding trauma starts with acknowledging that everyone comes to school with different life experiences.

Coming to school with different levels of trauma

Schonfeld says children who hear about violent events happening anywhere in the country are affected through a concept he calls “the loss of the assumptive world.”

“There are certain assumptions that people make every day that allow them to feel safe and secure in a world that does have a lot of dangers in it,” he said. “Whenever you hear that one of those assumptions is wrong … it makes you question all the other assumptions you have.”

In addition to this baseline vulnerability, children and teachers come to school with different levels of trauma that can be triggered by the drills.

“It’s hard for people to accept the fact that a lot of kids come to school and they may look fine, but that doesn’t mean that something bad hasn’t happened to them in the past,” Schonfeld said.

For Clements, the Newtown teacher, simple fire drills can be difficult.

“I remember in particular one fire drill. I remember grabbing onto my students, running out, crying,” she said. “They didn’t see me [crying] because they’re small, but my heart was racing.”

She’s not alone. Schonfeld, who travels to schools across the country as part of his work, explains that students and teachers who have been exposed to any violence in their homes or communities may relive these experiences during lockdowns.

“These events do come to the surface,” he said.

What experts recommend when designing lockdown drills

Experts understand the need to prepare for the worst but say there are best practices that can be followed to minimize the psychological impact of lockdowns on children and their teachers.

Teachers and students should always be aware of planned lockdown drills, Schonfeld said.

“The use of deception in any of these exercises is inappropriate and unethical,” he added.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Lockdowns should also be kept consistent – the same drill every time – with teachers offering frequent and calm reassurance, Schlozman said. he also recommends discussing the situation in small groups after lockdown events.

Schools should also avoid overly realistic scenarios, Schonfeld said.

As school officials partner with their districts to design safety plans, Dorn suggests that they be wary of programs using fear as a marketing strategy.

“We think these [safety] approaches can be taught in a more effective way if more balanced and accurate language and less fear is used,” he said.

Lastly, Schonfeld urges schools to remember to ask students what makes them feel safe.

As for Reed, she has continued to remind Vanessa that the school is very good at keeping everybody safe and that, because of this, she should listen to and follow her teacher’s instructions.