Editor’s Note: Kara Alaimo, an assistant professor of public relations at Hofstra University, is the author of “Pitch, Tweet, or Engage on the Street: How to Practice Global Public Relations and Strategic Communication.” She was spokeswoman for international affairs in the Treasury Department during the Obama administration. Follow her on Twitter @karaalaimo. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author; view more opinion at CNN.

The 2020 presidential election marks the first time more than two women have competed in the Democratic or Republican primaries, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. Democratic congresswomen Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, Kamala Harris of California, Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts have all thrown their hats in the ring. And Marianne Williamson, a bestselling author and a spiritual counselor to Oprah, is also running.

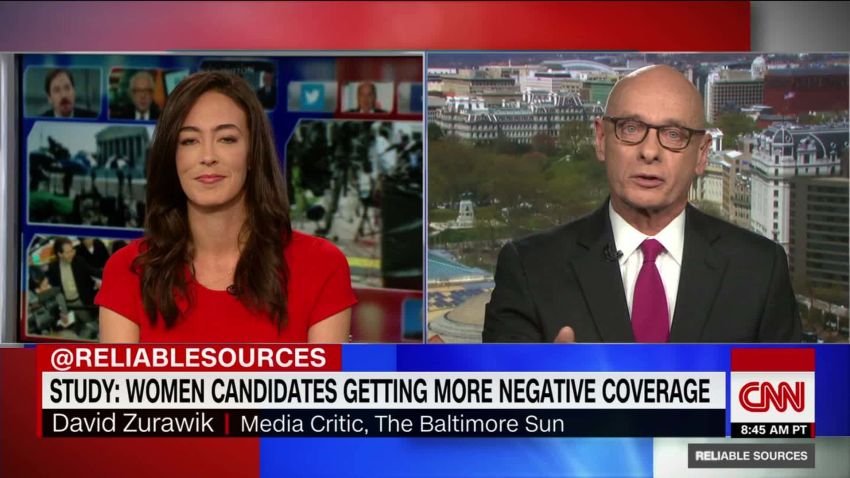

While this is refreshing to see, an analysis of media coverage published by Northeastern University’s School of Journalism finds that the percentage of positive words being used to describe the women is significantly lower than media sentiment about male candidates. But the problem isn’t just the media. Studies suggest women are likely to face extra hurdles to winning over voters, as well – simply because of their gender. In order for a woman to be elected president, a lot of us may need to re-examine some of our subconscious ways of thinking.

Research indicates that voters may unknowingly discriminate against female candidates for president because a woman has never held the position, and therefore a woman won’t appear to be a “fit” for the role. Scholars call this the gender-incongruency hypothesis. For example, studies have shown that female candidates don’t do worse than men when they run for local and state-wide office, but they don’t fare as well when they run for president.

In a 2007 study published in the journal Basic and Applied Social Psychology, when students were given identical resumes of candidates who they were told were running for president – a position which, of course, has never been held by a woman – they judged the candidate to have more presidential potential and to have had a better career when the candidate was named Brian than when the person was named Karen. But when students were shown resumes of candidates running for Congress – where women already hold seats – they didn’t judge Brian more positively than Karen.

A 2008 study of likely Ohio voters found similar results. When potential voters were asked about candidates who the researchers determined had similar credentials at the time – Hillary Clinton, Elizabeth Dole, John Edwards, Rudy Giuliani, and John McCain – they perceived the men to be more qualified. They were also more likely to vote for a candidate who was not in their own political party when the candidate from their party was female. The researchers noted that the results, published in the Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, suggest that “the presence of a woman candidate opponent for president may aid the competition.” (The language is telling in that they, too, appeared to assume “the competition” would be male).

Cornell University philosophy professor Kate Manne argued in her 2018 book “Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny” that when women run for public office or try to move into other domains that have typically been dominated by men, they are often judged hostilely by both men and women – and by liberals and conservatives alike. But, Manne said, voters often don’t realize they’re being misogynistic. Instead, she said, “Our minds subsequently search for a rationale to justify our ill feelings. Her voice is shrill; she is shouting; and why isn’t she smiling?”

Manne also reported in the book that women are less likely to be perceived as competent. When they are considered competent, they’re often disliked and considered polarizing. She said female candidates are also often judged to be untrustworthy “on no ostensible basis” and women’s claims are viewed as less credible than claims by men. Then, when women defend themselves from unfair attacks, they’re accused of “playing the victim.”

“To be sure, not every female politician … is subject to such suspicion, condemnation, and the desire to see them punished,” Manne wrote. “But, when the mud-slinging does begin, it quickly tends to escalate. And there tends to be not only a pile-on … but an ‘oozing’ effect – where the suspicion and criticism encompasses every possible grounds for doubt about her competence, character, and accomplishments.” Manne cited reactions to Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign as an example. She also noted that, like Clinton, former Australian prime minister Julia Gillard was portrayed by rival politicians and the media as a liar and investigated on allegations that ultimately proved unfounded.

What’s the solution? Manne told me that because these biases are so often unconsciously applied – even by well-meaning people who want women to advance, like herself – voters should engage in “candidate comparisons” when judging presidential contenders. “If you are critical of a woman on certain grounds, you should look toward your favorite male politician and see whether he has similar features,” she said. “It can actually be quite surprising how certain criticisms go under the radar when it’s a male candidate.” For example, Manne noted that Klobuchar has been accused in the media of mistreating her staff. (Klobuchar acknowledged in a CNN forum that she has sometimes been “a tough boss” and “pushed people too hard.”).

Yet Bernie Sanders – the frontrunner among declared Democratic candidates – has also been accused of mistreating his aides, but those allegations don’t seem to have gotten the same media attention. One former staffer told the Vermont newspaper Seven Days in 2015 that Sanders was “unbelievably abusive” and claimed “to have endured frequent verbal assaults.” The paper reported that others who worked for Sanders also said that “the senator is prone to fits of anger.” A spokesperson for Sanders responded to Seven Days and said that Sanders “had very positive relations with people who have worked with him.”) And Sanders, in response to the article, told the Des Moines Register, “Yes, I do work hard. Yes, I do demand a lot of the people who work with me. Yes, some people have left who were not happy. But I would say that by and large in my Senate office, in my House office, on my campaigns, the vast majority of people who have worked with me considered that to be a very, very good experience…”

Ultimately, the solution to women not appearing to fit the role of president because a woman has never been president seems obvious: Voters need to elect a woman president. But, in order for that to happen, even those of us who are eager to empower women may need to rethink how we judge female candidates.