The discovery of a rare, expensive blue pigment in the dental plaque of a medieval woman’s skeleton is shedding light on hidden chapter of history, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

Researchers studied burial remains from a medieval cemetery connected with a women’s monastery in Germany, where they believe a women’s community existed as early as the 10th century.

There are few records of the monastery itself because it was destroyed in a fire after a series of nearby battles during the 14th century, but written records there date to 1244.

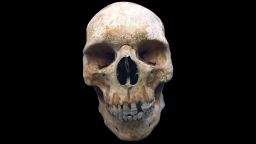

The researchers were studying a skeleton of a woman who was estimated to be between 45 and 60 years old when she died sometime between 997 and 1162. The skeleton itself was unremarkable, with no visible signs of trauma or infection.

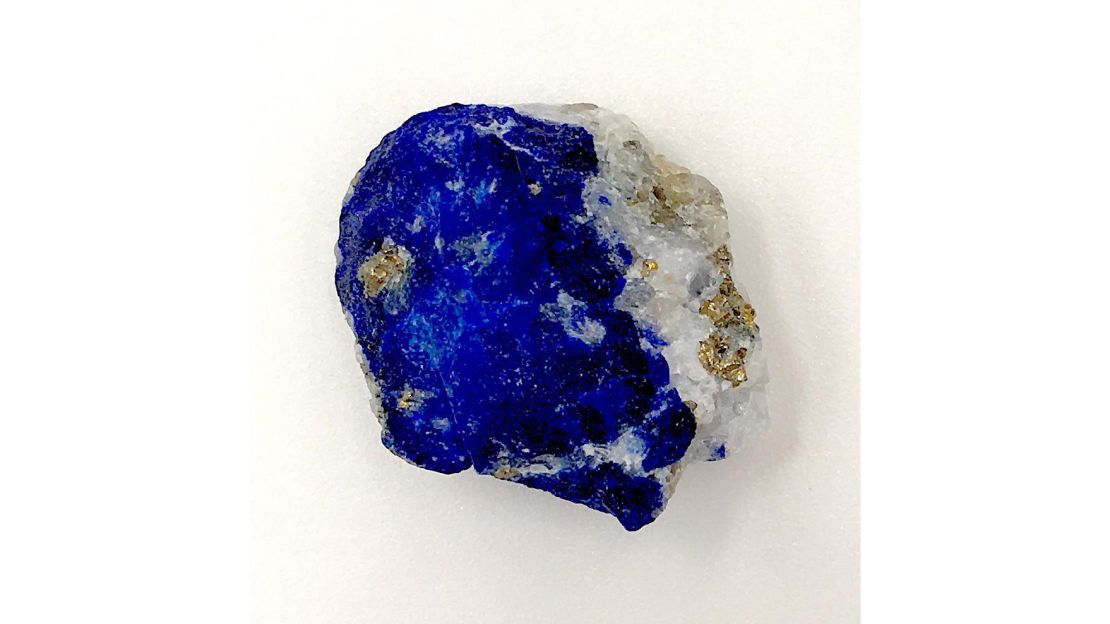

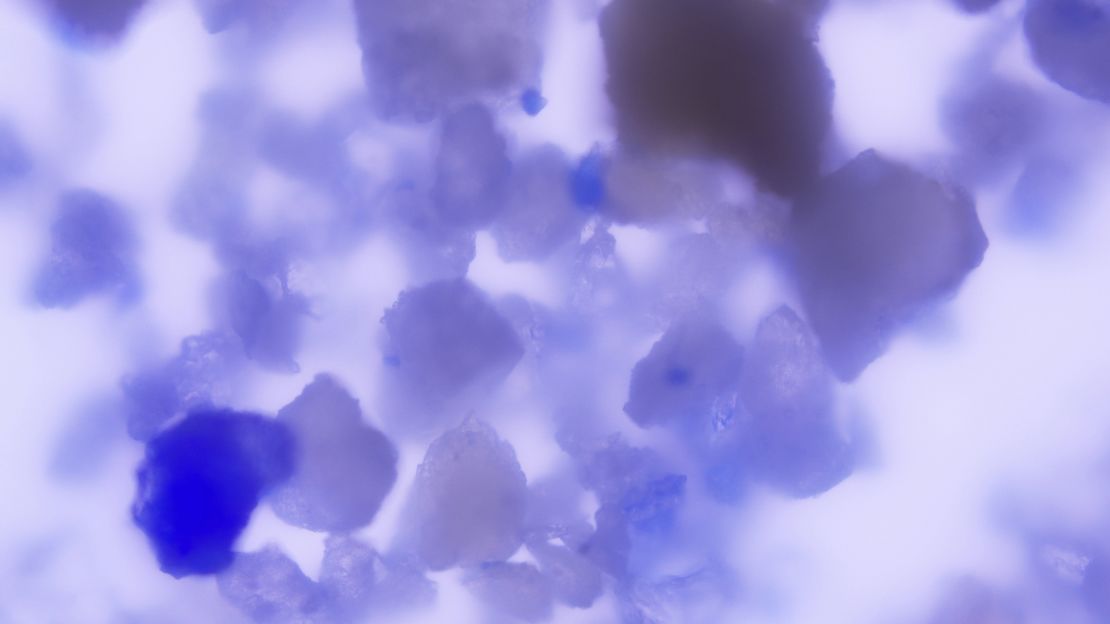

But blue flecks were embedded in her teeth. Multiple spectrographic analyses revealed the blue pigment to be ultramarine, a rare pigment made from crushed lapis lazuli stones. It was as expensive as gold at the time, mined from a single region in Afghanistan and the ultimate luxury trade good then.

Ultramarine and gold leaf would have been used to create illustrated illuminated manuscripts and luxury books in monasteries, mostly for other religious institutions and the nobility. Only the most skilled artists were allowed to use them because of their cost.

That the discovery was made in a rural German monastery is no surprise; books were being produced during this time in monasteries across the country. But women were not known to be the illustrators of such prized creations.

“Only scribes and painters of exceptional skill would have been entrusted with its use,” said Alison Beach, study co-author and historian at Ohio State University, in a statement.

In fact, the writers and illustrators often didn’t sign their work, as a gesture of humility – and if women were those writers and artists, the practice would effectively erase them from history. Monks were often assumed to be scribes over nuns.

The study says that even books found in the libraries of women’s monasteries have fewer than 15% of female names on them, and before the 12th century, that number drops to fewer than 1%.

But a few rare surviving works from as early as the eighth century reveal that women were scribes.

The researchers considered multiple scenarios for how the woman might have come into contact with the pigment. But only one seemed truly viable.

“Based on the distribution of the pigment in her mouth, we concluded that the most likely scenario was that she was herself painting with the pigment and licking the end of the brush while painting,” said Monica Tromp, study co-author and microbioarchaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, in a statement.

In fact, given the destruction at the site due to the fire, this woman’s skeleton may be the only record of the activity at the monastery.

“She was plugged into a vast global commercial network stretching from the mines of Afghanistan to her community in medieval Germany through the trading metropolises of Islamic Egypt and Byzantine Constantinople,” Michael McCormick, study co-author and historian at Harvard University, said in a statement. “The growing economy of 11th century Europe fired demand for the precious and exquisite pigment that traveled thousands of miles via merchant caravan and ships to serve this woman artist’s creative ambition.”

There was little evidence for physical labor in her skeleton, which aligns with the understanding that German women in medieval monastic communities were often highly educated aristocrats or nobles.

“Here we have direct evidence of a woman, not just painting, but painting with a very rare and expensive pigment, and at a very out-of-the way place,” said Christina Warinner, senior study author and anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, in a statement. “This woman’s story could have remained hidden forever without the use of these techniques. It makes me wonder how many other artists we might find in medieval cemeteries – if we only look.”