Editor’s note: The UN estimates that around 17 million people born in India live outside its borders. The group is considered the world’s largest migrant population. From the NBA’s first Indian-origin player to the descendant of an indentured laborer, CNN spoke to a handful of people born to Indian parents who settled overseas.

When Shani Dhanda was born, her parents knew something was wrong.

Her mother found a way of cradling her so she wouldn’t cry, but when others held her she’d scream in pain.

“No one knew what my condition was,” says Dhanda, 31.

Finally, when she was two years told, Dhanda was diagnosed with brittle bone disease, a genetic condition that affects around 1 in 15,000 people in the UK.

Sufferers have fragile bones that break easily and can have problems breathing.

Not everyone reached out lovingly. Dhanda found out recently that a relative had told her mother: “Not only have you had another girl, but she’s not even right.”

“I was horrified,” Dhanda says of the discovery.

Dhanda’s bones broke frequently as a child – by the time she was 14 she had broken her legs six times.

But she says her mother didn’t treat her differently to her siblings and her disability was never used as an excuse to avoid tough tasks.

“I remember being at home and my leg would be in plaster, but she’d give me a pile of laundry to fold, because why should I get away with not having to do the chores?

“I’m really glad that she… instilled that value in me from a really young age, because (otherwise) I would have grown up and expected everyone to treat me differently.”

But parts of society have indeed treated her differently.

Dhanda’s mother was born in the central English city of Birmingham of parents who had emigrated from the northern Indian state of Punjab in the 1950s.

Her father was born in the Punjab city of Jalandhar and came to the UK with his family as a child in the mid-1960s. Like her mother, Dhanda was born in Birmingham and from childhood, her family regularly visited a Sikh temple.

“As a teenager, people (at the temple) would ask my mom how I was when I was standing right next to her. And I’d (say), ‘I’m here, you can ask me.’”

At age 15, she applied for 100 jobs and got no replies – until she removed a line from her covering letter which mentioned her medical condition.

Some people in her Indian community said she should stay home and claim benefits, but Dhanda defied them.

She worked for three years while studying for a degree in Events Management, which she describes as one of her biggest achievements.

“Ironically, I was one of the first people in my class that graduated and got a job.”

After graduating she set up her own freelance events management company, organizing events for the likes of British boxers Anthony Joshua and Tyson Fury.

In her present career as a disability program manager for Virgin Media, Dhanda works to shape company policy.

“If I didn’t have my condition, I wouldn’t have the drive to be like this.”

In recognition of her advocacy, Dhanda was selected as one of the UK’s most influential disabled people by the annual The Shaw Trust Power List.

But change takes time.

‘Nothing’s changed in a generation’

“I met somebody… who was 10 years younger than me, but he has had similar experiences to me. And that saddened me because it means nothing’s changed in a generation.”

She says conversations about disability usually consist of “white faces.”

“They don’t speak on behalf of me or my experience, or other ethnic minorities… I had to fight for a seat at the table.”

The fight continues outside the boardroom.

While she loved growing up in multicultural Birmingham, she would sometimes be stared at. “People often think that I can’t hear what they’re saying about me. They’ll say, ‘Look at that dwarf or midget.’”

What they don’t expect is for Dhanda to go up and challenge them – something she says she found the courage to do, so that others more vulnerable than herself don’t suffer the same experience.

It’s not just disability rights that Dhanda fights for. This year, she used her events management skills to self-fund an Asian Woman Festival in Birmingham.

“As an Asian woman, I’m not interested in booking a wedding or buying a new sari. Those are the only events that exist.”

People flew in from European countries and even Singapore to attend the festival. But Dhanda says she found it difficult to get high-profile Asian women as her allies.

“In the Asian community, we don’t support each other enough… It’s mad, because we all want the same things.”

But the show will go on. Dhanda is planning the next festival for 2020 as well as pop-up events in the capital, London, as well as the British city of Leeds.

When she’s not campaigning, Dhanda loves traveling and has visited 31 countries. “I have a short stature of three foot 10 (116 centimeters), so my suitcase is often bigger than me,” she laughs.

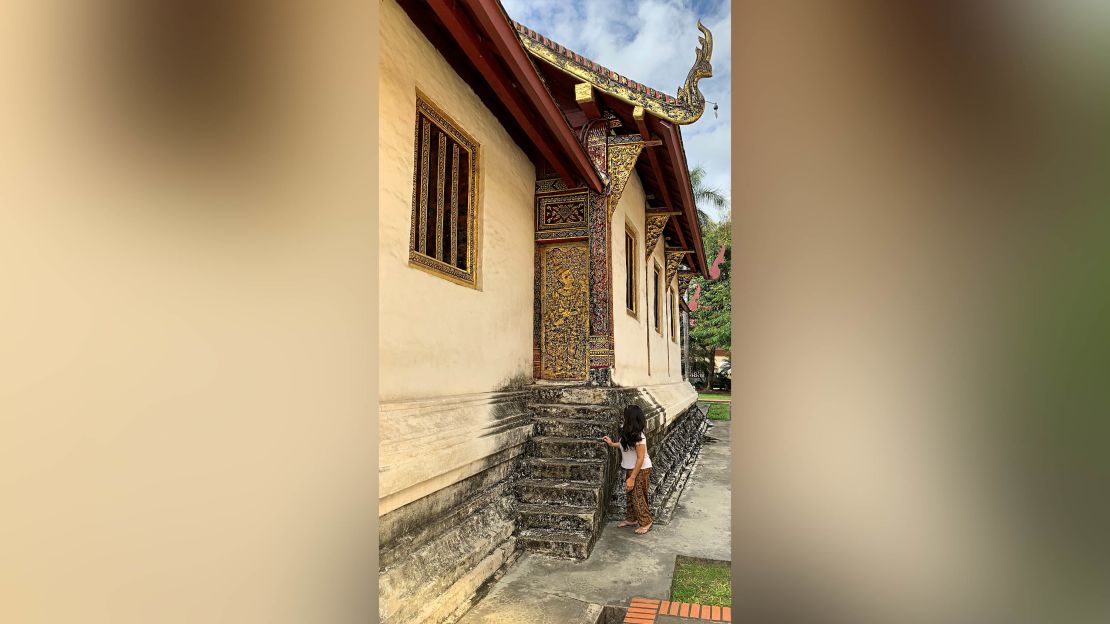

And while she’s been to India many times, she embarked on a life-changing solo trip to the country in 2016, against the wishes of her worried parents.

Disability doesn’t discriminate who it affects

Living in London has its own challenges. Having almost been knocked onto the tracks at an underground station, Dhanda drives an adapted car.

Because of her height, she has stepladders installed in her apartment and uses her dishwasher for storage.

She describes living with her condition as “a full-time job.” But her family, community and faith have helped her thrive.

Dhanda says “the world isn’t designed” for those with a condition or impairment – and in the UK that means almost 14 million people.

According to government statistics, 83% of disabled people acquired their condition while they were in work.

“That means that disability can affect anyone at any time, it doesn’t discriminate who it affects,” Dhanda says.

“It baffles me. It’s the largest diversity strand, but it’s the most overlooked.”