The stunning increase in homelessness announced in Los Angeles this week — up 16% over last year citywide — was an almost incomprehensible conundrum given the nation’s booming economy and the hundreds of millions of dollars that city, county and state officials have directed toward the problem.

But the homelessness crisis gripping Los Angeles is one that has been many years in the making with no easy fix. It is a problem driven by an array of complex factors, including rising rents, a staggering shortage of affordable housing units, resistance to new shelters and housing developments in suburban neighborhoods, and, above all, the lack of a cohesive safety net for thousands of people struggling with mental health problems, addiction and, in some cases, recent exits from the criminal justice system that have left them with no other options beyond living on the streets.

“It is the height of contradiction that in the midst of great prosperity across the Golden State, we are also seeing unprecedented increases in homelessness,” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, a key proponent of the 2017 county sales tax known as Measure H that is raising about $355 million annually for homelessness services over ten years.

“This data is stunning from the perspective that we had hoped that things would be trending differently, but we will not ignore our realities,” Ridley-Thomas said after the numbers were released. “No one can ignore the income insecurity, the financial stress that is being experienced throughout the population. … This is a state that is the wealthiest in the nation, and, at the same time, it is the most impoverished.”

The new homeless count released Tuesday by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority showed nearly 59,000 people living in the streets across Los Angeles County, a 12% increase over the prior year; and 36,300 homeless people within the city limits of LA, a 16% increase over last year’s count.

While those figures were shocking to many Americans who view Los Angeles mainly as a city of glittering wealth, they came as less of a surprise to millions of Angelenos.

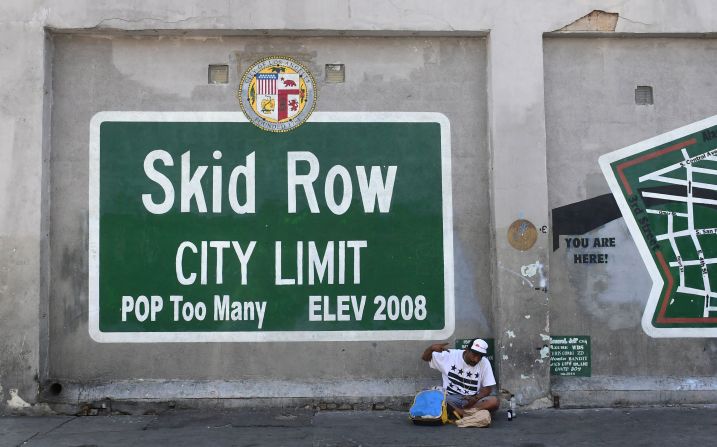

For several years now, the city’s residents have watched tent encampments spring up far beyond the downtown area known as Skid Row – where LA’s homeless population and services have historically been concentrated – to their neighborhood sidewalks, freeway embankments, city and county parks, along business corridors and into some of the most affluent neighborhoods of Los Angeles.

Beyond the well-being of the city’s homeless population, the encampments have raised a broad array of public heath and safety concerns. Los Angeles Fire Department officials determined, for example, that the massive Skirball blaze that burned homes in Bel-Air and torched the hillsides along the 405 freeway in December 2017 was sparked by a cooking fire at a homeless encampment nearby.

In and around Skid Row, scores of business owners who warehouse their goods in that industrial area downtown have pressed the city to do more about the rising number of tent fires. In one of the most frightening developments, some of the fires are being lit by gang members who try to collect rent from tent-dwellers on certain blocks, according to law enforcement officials and homeless people living in tents interviewed by CNN.

In pictures: L.A.'s homelessness crisis

Many homelessness advocates and officials interviewed by CNN over the past year are also worried that the proliferation of tents has made it far easier for gang members and other criminals to conceal human trafficking and drug trafficking, particularly in Skid Row where the trash along the streets is littered with used needles, a glaring public health hazard.

Though the city does routine cleanups in Skid Row and in other parts of the city, trash from abandoned encampments is a constant eyesore, littered across freeway exits and under bridges. In part because of the public health hazards, the cleanups in Skid Row are carried out with military precision. Advance notice is posted for the homeless residents who live on that block to move their tents so the streets can be cleared of trash, swept by massive street sweepers, and then sprayed down with disinfectant in workers wearing white Hazmat suits. Clothing and trash piled up along the corridors in other parts of the city sometimes takes weeks to get cleaned up.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, who campaigned intensively for the city initiative known as Proposition HHH that designated $1.2 billion over the next 10 years for units to house the homeless, described homelessness in an interview with CNN as “the biggest heartbreak for me and my city.” The crisis was widely viewed as the central reason Garcetti decided not run for president in 2020.

During a kickoff event in March 2018 for a project that aimed to end homelessness for about 45,000 people, Garcetti launched what amounted to a citywide campaign to encourage Angelenos to welcome more shelters and affordable housing in their neighborhoods.

“We can’t arrest our way out of this. We can’t shelter our way out of this. We have to house our way out of this,” Garcetti told reporters then.

In a budget proposal for the fiscal year beginning July 1, California Gov. Gavin Newsom said he was seeking $1 billion to address the state’s homelessness crisis. The governor tapped Ridley-Thomas and Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg to co-chair his Homeless and Supportive Housing Advisory Task Force to help guide local jurisdictions on the best ways to spend the money (either on supportive housing or more innovative approaches like motel conversions).

The new report this had one glimmer of hope: statistics showed that the better-equipped city/county homeless crisis response system helped move 21,631 people into permanent housing last year.

But the housing money has flowed slowly. And while that housing figure was viewed as progress, Garcetti has run into major resistance even with his attempt to convince each of the city’s 15 council districts to approve a temporary shelter.

At a public forum in Venice on LA’s west side last October, Garcetti faced shouting protests and catcalls over the course of four hours as he tried to convince residents to support opening a shelter in a vacant lot as part of his “Bridge Home” project. The neighborhood’s residents cited concerns about crime, disruption, trash and needles that are already a problem in their streets.

This week faced with the grim numbers, the LA mayor vowed to carry on.

“We cannot let a set of difficult numbers discourage us or weaken our resolve,” Garcetti said.