Editor’s Note: Samantha Allen is a journalist and author of the books “Real Queer America: LGBT Stories from Red States” and “Love and Estrogen.” The views expressed here are the author’s. Read more opinion on CNN.

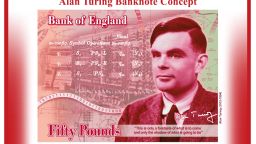

Alan Turing changed the face of history, so it’s only fitting that his face be on the currency of the country that once punished him for being gay.

That’s exactly where the pioneering mathematician’s visage will be seen for years to come: Bank of England Governor Mark Carney announced on Monday that Turing, who helped lay the groundwork for modern computing and worked to crack Germany’s Enigma code during World War II, would be the face of the new £50 note.

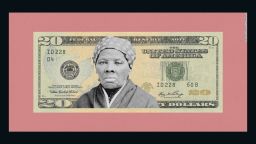

But the new currency isn’t just a celebration of Turing’s heroic accomplishments; it is also a kind of extended apology – or, at least, an overdue recognition of the harms that he was subjected to because of his sexual orientation. The Trump administration, which so far has not seemed passionate about the plan to make Harriet Tubman the face of the new $20 bill, could afford to take note.

What the Bank of England’s £50 redesign announcement proves is that currency can be a literal and tangible medium for processing—and helping to expiate—the wrongs that countries have inflicted on heroes that they can only fully appreciate posthumously. LGBTQ people and people of color have literally given their lives to improve countries that have criminalized their mere existence; honoring them on currency is the least that can be done.

Convicted of “gross indecency” in 1952 after it was discovered that he was in a relationship with a man, Turing was only able to dodge imprisonment by agreeing to take female hormones. He took his own life two years later.

The Bank of England’s official announcement of the £50 note acknowledges that “Turing was homosexual” and that he was “posthumously pardoned by the Queen” in 2013 for the 1952 “gross indecency” conviction. Former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown also apologized in a 2009 statement for the “horrifying” and “utterly unfair” treatment Turing endured at the hands of the state.

But as far as statements go, few are more visible or more public than putting somebody’s face on a bill. This is one of the most literal examples to date of “putting your money where your mouth is.” On top of apologizing for Turing’s conviction—and indeed, in addition to pardoning him—the Bank of England is literally imbuing his face with value.

At a fundamental level, putting Alan Turing’s face on the £50 note is an act that says, “This man was worth something—and he is worth remembering.”

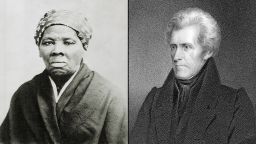

Contrast that with President Trump’s reported feelings about the plan to replace former president Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 bill with Harriet Tubman, a heroic black abolitionist who helped free slaves through the Underground Railroad.

During his 2016 campaign, Trump called the Obama-era move “pure political correctness,” but at the very least least acknowledged that Tubman is “fantastic.”

Both Trump and Ben Carson, who is now the secretary of Housing and Urban Development, have proposed putting Tubman on the $2 bill instead.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin also sparked outrage earlier this year when he shared that the Tubman $20 might not be available until later in the next decade, saying, “I am not focused on that at the moment.”

The Washington Post reported on Monday that former Obama officials doubted that the $20 bill redesign was going to be ready in the near future anyway, with one saying that the tail end of the 2020s was always the target date. That reporting casts doubt on the notion that the Trump administration is actively delaying Tubman’s appearance on the $20, painting a picture instead of a slow-moving bureaucratic process for the redesign.

But still, as the Post acknowledged, Mnuchin “has not shown … enthusiasm” for the plan to put Tubman on the $20 bill and Trump has “previously dismissed it.”

Gone is the glowing rhetoric that Obama-era Treasury Secretary Jack Lew used to describe Tubman in his 2016 announcement of the plan, in which he called her “not just a historical figure, but a role model for leadership and participation in our democracy.”

Lew also talked about the “thousands of responses” that he had “received from Americans young and old” in support of the idea of putting Tubman on the $20 bill, and it’s easy to see why she inspires such passion: Tubman fled slavery herself, only to risk everything on expeditions that ultimately freed dozens of other slaves.

The Civil War ended and the Thirteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution, but Tubman kept fighting for equality within the early suffragist movement. She lived a long life, but not long enough to see the culmination of her work: her 1913 death preceded the ratification of the Nineeteenth Amendment by seven years and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by decades.

Tubman, like Turing, was a history-changing pioneer who faced discrimination based on an innate and unchangeable characteristic. Both figures are more than worthy of appearing on the paper money of two of the world’s largest economies. And given that Tubman was born into a country where people like her were literally bought and sold, it’s hard to overstate the significance of her potentially being honored as a hero on United States currency.

Seeing Alan Turing’s face on paper money, ubiquitous as it is, will foster a level of public awareness that nothing else can match. No pardon, no apology, no public address can match the long-term name recognition of someone’s face being in your purse or wallet. We’ll get to see the impact of that firsthand when the Turing £50 note enters circulation “by the end of 2021,” according to the Bank of England’s estimate.

If the Trump administration can’t get Tubman on the $20 as fast by then, they could at least show that they understand what it would mean for her face to be on money.

This isn’t “pure political correctness”—it’s about acknowledging and correcting, inasmuch as we can, a deep historical wrong.