Editor’s Note: Naaz Modan is the former executive editor for Muslim Girl, a publication focused on Muslim women’s issues and empowerment. She is currently the communications manager for the Council on American-Islamic Relations, the nation’s largest Muslim civil rights and advocacy organization. The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

I am a birthright citizen. My parents, enchanted by the promise of a better life and working their way into American society, planted their Indian roots in a northern Jersey suburb in the early 1980s where a dozen or so of my other family members would eventually migrate over the next two decades. We would go on to become cooks, mailmen, doctors, journalists, nurses and real estate agents, and disperse along the East Coast to places like New York, Washington, North Carolina, Virginia and Connecticut.

But the American dream that my mother and father realized nearly 40 years ago, beyond JFK’s terminal gates with green cards in hand, is under attack. President Donald Trump says he intends to revoke the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment – which guarantees citizenship for all children born in the United States – via executive order. Regardless of the constitutionality of this, it directly targets the right to an American identity that many first-generation Americans like myself claim.

I was raised with a hodgepodge of identities: Muslim, Indian, American, child of immigrants. Despite the different facets of my background – and perhaps because of them – I have always carried a United States passport and placed a check mark next to “US citizen” without a second thought. I have always entertained the possibility that I could one day run for president if my whims led me to.

Now, my American-ness is being called into question. Just as it was following September 11th and the 2016 elections, my identity is once again a subject of debate. Is my life less “American” just because I was born to naturalized citizens who have spent a majority of their lifetime on American soil?

What may come as a surprise to self-proclaimed nationalists like Trump is that not only am I as American as the next citizen, but, in many ways, my story and the story of many other first-generation citizens is the American story that historian James Truslow Adams famously spelled out. In 1931, Adams coined the term “the American dream,” which he described as “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability and achievement,” regardless of circumstance of birth. We are the walking, talking, realized American dream.

Considering that the idea of the American dream has roots in the Declaration of Independence (“all men are created equal” with the right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”) and US Constitution (“secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity”), one could even call Trump’s desire to revoke birthright citizenship inherently un-American. Although many groups throughout history were not afforded equal rights and many continue to be subject to discrimination, the ideal of equality has been rooted in the foundations of this country since the beginning.

After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment was put in place as a way to curb states’ power and protect the civil rights of former slaves. The citizenship clause provided them equal legal status.

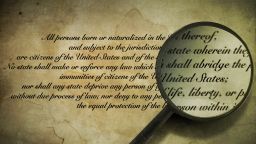

The clause states that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.” While some argue that the second part of the amendment – “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” – is misinterpreted and doesn’t grant citizenship to children of noncitizens born on US soil, the 1898 Supreme Court case US vs. Wong Kim Ark disqualifies any such argument. The decision held that a child born in America to parents who are subjects of another government at the time of birth is still a citizen of the United States by virtue of the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment.

To say that I, along with millions of other citizens, am undeserving of an American title insinuates that we are lesser in the eyes of the government due to nothing more than the national origin of our parents – a dangerous idea for a United States president to harbor.

Until now, it seemed presidents understood that this country was built on a set of shared ideals – democracy, rights, liberty, opportunity and equality – and respected the work ethic that immigrant families brought with them in pursuit of these ideals. It comes as no surprise that a man who called himself a nationalist just one week ago is now undermining these values.

And so when Trump attacks us and our families, he’s delivering a blow to America’s national ethos and the immigrant communities that encapsulate it.

But it is exactly the ingrained ethic of hard work and determination that will help us resist this discrimination. We will protest, we will write and we will show up to polls because we know that we deserve to be heard. More importantly, we have a birthright to this country and have the power to determine which direction it takes.