Time is the most crucial element when it comes to treating patients who are experiencing a stroke – and a new study suggests that that crucial window could be a little longer than previously thought.

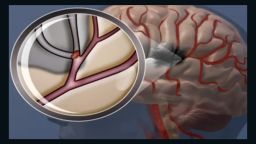

Thrombolytic medicine, which helps break up blood clots, typically is administered to treat an ischemic stroke within 4½ hours of the start of symptoms.

Yet the study, published in The New England Journal of Medicine on Wednesday, suggests that treatment between 4½ and nine hours after stroke symptoms emerged still could offer benefit.

A thrombolyic drug called alteplase is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat acute ischemic stroke and is administered through an IV. Most strokes, about 87%, are ischemic strokes, which occur when the artery that supplies oxygen-rich blood to the brain gets blocked, often by a collection of blood called a clot.

Even though the new study findings are “exciting,” Dr. Carmelo Graffagnino, a vascular neurologist at Duke Health and medical director of the Duke Comprehensive Stroke Center in Durham, North Carolina, pointed out that the American Stroke Association and other medical groups have not weighed in as far as making formal changes to stroke treatment guidelines.

With additional research, however, that could happen.

“What was really exciting is that in vascular neurology, or stroke, we were forever stuck with treating patients by the clock rather than by what was actually going on in their brain,” said Graffagnino, who was not involved in the study but saw parts of the research presented at the International Stroke Conference in February.

“We think this is just the beginning of using biology and not the clock to treat the right patients,” he said.

In the United States, someone has a stroke every 40 seconds, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A benefit for rural or low-income health centers

The new study involved 225 adults who had strokes between 2010 and 2018 in Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan and Finland.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive either a thrombolytic therapy or placebo between 4½ and nine hours after the onset of their strokes.

The researchers found that recanalization, or restoration of blood flow, was achieved at 24 hours after the stroke in 67.3% of the patients in the therapy group, compared with 39.4% in the placebo group.

The study also found that the degree of disability after the stroke, measured on what’s called a modified Rankin scale, was zero or minimal among more patients in the therapy group, at 35.4%, compared with the patients in the placebo group, at 29.5%.

The percentage of patients who died within 90 days of treatment or placebo did not differ significantly between the groups, according to the study.

“About 80% of the patients in this trial had large vessel clots, which means that they would actually be candidates for mechanical thrombectomy – for pulling the clot out using a catheter – and the success rate of pulling a clot out by catheter is much higher than the success rate of dissolving a clot with a medication,” Graffagnino said.

If a patient may not have access to thrombectomy, however, the study suggests that thrombolysis could be a beneficial option.

“This has really big implications for more distal places, more rural hospitals that are quite far from an advanced treatment center, for low- or middle-income countries where interventions, such as thrombectomy, are limited due to their resources,” he said.

Globally, about 70% of strokes and 87% of both stroke-related deaths and disabilities occur in low- and middle-income countries, according to the World Health Organization.

The new study had some limitations, including a sample size smaller than intended, because the research was terminated early after positive results from a previous trial were published.

‘The era of time-based treatment … may finally be drawing to a close’

The new study “reinforces the importance of individualizing acute stroke treatment and not simply excluding patients because of the time they were last seen normal,” Dr. Fadi Nahab, medical director for the Stroke Program at Emory University Hospital, who was not involved in the study, wrote in an email.

Many hospitals offer IV alteplase only if a patient experienced stroke symptoms within 4½ hours and exclude those who may have awoken from sleep with stroke symptoms because the onset time would be unknown, Nahab said.

So the extension of that time window provides “stroke center hospitals with additional opportunities to treat patients who come in within 4.5 to nine hours or who develop new stroke symptoms on awakening from sleep,” he said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Even though more research is needed to validate the study’s findings, “the era of time-based treatment with intravenous alteplase in patients with acute stroke may finally be drawing to a close,” Dr. Randolph Marshall, a neurologist at Columbia University in New York, wrote in an editorial published alongside the new study.

“As of 2013, only 6.5% of patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke in the United States received intravenous thrombolysis treatment,” he wrote. “Extending the time window for treatment could result in greater numbers of patients eligible to receive treatment for acute stroke.”