Editor’s Note: Leon Fresco is an immigration attorney in Holland & Knight’s Washington office and former deputy assistant attorney general for the Office of Immigration Litigation and former staff director for the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Refugees, and Border Security. The opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author; view more opinion articles on CNN.

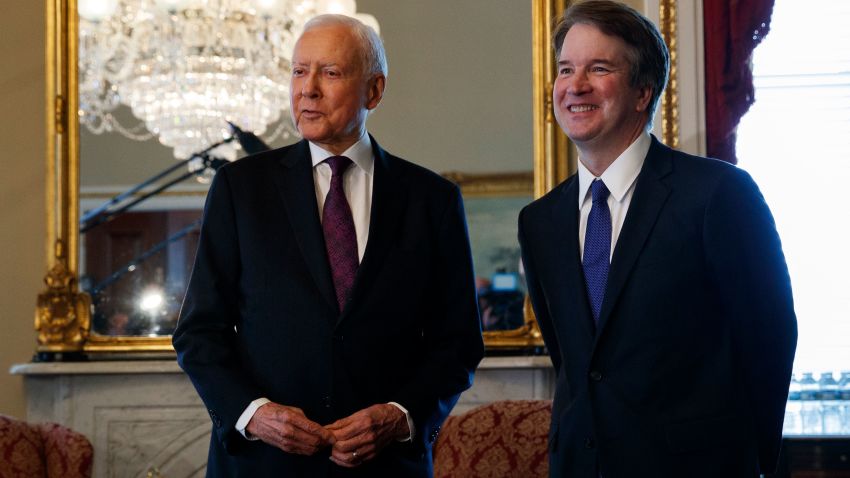

Now that Brett Kavanaugh has been nominated for the Supreme Court, a lot of attention is rightfully being focused on what his positions will be on issues such as Roe vs Wade, the Affordable Care Act, executive power, voting rights, and affirmative action.

But little attention has been focused on the fact that — for at the least the foreseeable future — this Supreme Court will be dealing with a series of looming immigration cases with far-reaching consequences.

Because the D.C. Circuit Court is neither near the border nor reviews immigration removal cases, Kavanaugh’s record on immigration cases is relatively sparse. That is why senators should ask him his thoughts on certain bedrock immigration precedents that are hanging on by the thinnest of threads.

The Supreme Court on which Kavanaugh may very well sit could well decide on such monumental issues as the fate of the DACA program, the proper role of states and cities in immigration enforcement, the ability to separate parents and children for immigration enforcement purposes, and the ability to detain immigrants without bond during their removal proceedings, the latter of which was already addressed by the Supreme Court and remanded to lower courts for further review and will likely return to the high court in the future.

All these cases are working their way up the lower courts for ultimate resolution in the Supreme Court. Out of 80 or so cases per year, it is possible that 10 or more of these cases could be immigration cases for the remainder of the Trump administration.

Almost all these issues will likely be decided by a razor-thin margin. But the outcomes are difficult to predict. Chief Justice John Roberts voted for the Obama administration’s position in the case challenging the legality of Arizona’s state law criminalizing illegal immigration (Arizona v. US) while Justice Neil Gorsuch provided the fifth vote in favor of increased due process rights for certain noncitizens with criminal convictions in Sessions v. Dimaya. In other words, as far as the fate of American immigration law is concerned, a future Justice Kavanaugh would be a pivotal vote.

For instance, the 1982 Plyler v. Doe decision established that undocumented children can attend public school in the United States regardless of their immigration status. But if even one state passed a law requiring proof of legal status as a condition for entering public school, it is conceivable that this new Supreme Court could overturn the 5-4 decision in Plyler.

Birthright citizenship – that anyone born in the United States is automatically a US citizen – is a concept that is generally taken for granted. But the 1898 decision this principle rests upon, United States v. Wong Kim Ark, can be limited by a future court, which might limit birthright citizenship only to children of permanent residents. A future Supreme Court could hold that the clause does not confer automatic citizenship on the children of people present in the United States without legal authorization.

All it would take is for one state to decide to not provide driver’s licenses to anyone who cannot prove that they were born to at least one parent who was a US citizen or lawful permanent resident. In that case, would the court uphold the concept of birthright citizenship or would they adopt the position long held by immigration restrictionists (including President Trump) who have argued that the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause does not apply to the children of undocumented immigrants?

Finally, under the 2001 Zadvydas v. Davis decision, the United States cannot simply keep immigrants locked up in a detention facility indefinitely if the government is unable to deport them to their native country. But Zadvydas was a 5-4 decision. What if President Trump decided to lock up hundreds of thousands of immigrants for as long as he deemed necessary to try to force their countries of origin to accept the return of these individuals? Would the court uphold Zadvydas or would it side with the President?

If and when these issues make their way to the Supreme Court, they are likely to be decided on a 5-4 basis.

It is therefore tremendously important for the Senate to ask these questions of Kavanaugh so the American people will know what his views are on one of the most politically controversial issues in America today.

Firstly, Kavanaugh would be on far less stable ground refusing to discuss his views on past cases that have already been decided. Secondly, even if he does not directly answer these questions, he will still likely be prompted to discuss his overall approach to immigration and the amount of deference he believes should be given to the administration under the Constitution, which may provide clues about his general approach to adjudicating cases involving due process and challenges against the federal government.