You’ve been quarantined.

Those scary words upended the lives of more than 1,000 students and faculty at UCLA and California State University in Los Angeles over the past few days as authorities raced to contain a potential measles outbreak.

As of Friday morning, 628 people were still under individual quarantine at Cal State LA, with another 46 still in isolation at UCLA, said Dr. Barbara Ferrer, director of the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Those are just the people the health department has been able to identify, Ferrer said. A blanket quarantine has been issued for anyone who visited the North Library on the Cal State LA campus during the time of exposure, between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. on April 11, Ferrer said. Those people, she said, are being asked to self-identify, stay home and reach out to public health authorities to verify their immunization status.

Cal State LA senior Anthony Quach was on his way to work Thursday when he learned he might have been exposed to measles at the library, where his office is located. Because the school couldn’t verify his immunization records, he couldn’t go to work or school.

“I know I got my shots as a child,” Quach said. “I remember seeing my immunization records.”

Quach was able to reach his parents and get his records to the student health clinic on Friday. Still, the clinic told him he was still under quarantine until he was cleared by the local health department.

“It’s frustrating and a little annoying because I’m trying to finish off the semester, not to mention finals are coming up next month,” Quach said.

UCLA junior Jade McVay said she was more than frustrated – she was frightened. She, too, was sent into quarantine Thursday when the student health center couldn’t verify her immunization status.

“The nurse pulled me to the side and said, “You were actually in the same classroom as the student who had the measles. Do you know if you had the booster shot?’

“And I was little, I didn’t remember,” said McVay. “So, I was getting really worked up, thinking ‘Am I carrying this disease that could harm me and everyone around me?’”

Like Quach, McVay was able to quickly reach her parents, who verified she had both shots and rushed her records to the UCLA clinic. She said she considers herself lucky. She was quarantined for only two hours; several friends have spent more than 18 hours in isolation.

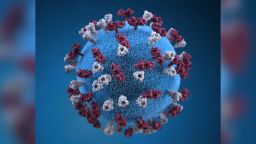

Measles cases in the United States have surpassed the highest number on record since the disease was declared eliminated nationwide in 2000. Many of the cases have been in strongholds of vaccine-wary parents, swayed by anti-vax misinformation and distrust of authorities.

But it was only a matter of time before it appeared at a college campus, said Georgetown University’s Lawrence Gostin, who directs the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.

“Campuses really are hotbeds of infectious diseases,” Gostin said. “Young people are in close contact, being intimate, eating food together, living together in dorms.”

It’s such a high-risk environment, Gostin said, that every simulation he creates on an infectious disease outbreak “begins on a college campus and then spreads to the city, and then state and country.”

Preparing for an outbreak

Well aware that infectious disease can spread like wildfire within a student population, many universities actively prepare for such scenarios. Georgetown University, Gostin said, is getting ready for its yearly “pandemic preparedness simulation” in which they explore what might happen if an infectious disease is discovered on campus.

“Simulations are a really good thing to do,” Gostin said, “because you can’t know whether you can respond effectively if an outbreak occurs. You have to practice, practice, practice.”

Did UCLA and Cal State LA have such plans in place? CNN’s emails to health officials at both universities asking about simulations and preparedness plans went unanswered, and neither McVay nor Quach said they recall any such practice during their time on campus.

“In my four years of being here at Cal State LA, I’ve never had to do that. I’ve never been informed of that,” Quach said, adding that it would be been helpful because “people wouldn’t be so scared. They’d know what to do.”

Quarantine as an effective, if controversial, measure

Using quarantines to assist in controlling an outbreak, while uncomfortable, is an important public health option, said Rebecca Katz, who directs the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University.

“Quarantine is a word that people respond to very strongly, but it’s actually one of the strongest tools in the public health tool kit,” Katz said. “But because it curtails civil liberties, most public health officials are very wary to utilize it.”

Every state has laws in place that allow quarantines and other public health enforcement tools, and they differ based on the jurisdiction. For anyone who refuses to cooperate, actions can range from issuing a self-isolation order to “checking in once a day via the internet, to putting a tracking device on somebody, to placing an armed guard outside of their home,” Katz said.

“Sometimes people feel like they’re being treated like a criminal,” Katz added. “The point is to be treated like you’re doing something that is contributing to your society and only be treated like a criminal if you disobey.”

Universities often wait until the local public health department insists that such measures are necessary, said Dr. Timothy Moody, who chaired the emergency response coalition for the American College Health Association.

“Most universities would like the public health people to take the lead,” Moody said. “They are reluctant to do anything that could be perceived as restricting students.”

While the threat of measles is a new challenge, colleges have faced such situations before. The H1N1 flu pandemic of 2009 to 2010 hit schools and universities hard. In the beginning, schools were urged to close for two weeks; later the CDC urged faculty and students to self-isolate at home instead.

Harvard relocated students during a mumps outbreak in 2016 to isolate those infected in a single room with an en suite bathroom instead of the typical shared rooms and bathrooms. Other universities have done the same, despite grumblings from student populations.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

While the nation struggles to contain the growing threat of measles, experts predict that more universities will see outbreaks like that at UCLA and Cal State LA. And while public health officials scramble to identify everyone who might be at risk, quarantines are a likely option.

“These things are well within traditional public health powers,” said Gostin. “I think they are constitutional, I think they are ethical, and I think if they were well enforced they would be effective.”