Helga Ögmundardóttir has been feeling a bit guilty this summer. The Icelandic academic lives on the coast in Reykjavik and isn’t used to sitting on her balcony without a blanket. This year though, she’d happily spend evenings outside wearing short sleeves.

“I’m in my garden and I’m sweating because it’s 20 degrees and it’s midnight and I feel this guilty pleasure because I know it’s a bad thing, but it’s nice and I want to enjoy it,” she said.

July was the hottest month on record in the Icelandic capital, with temperatures 1.4 degrees Celsius (2.5 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than the average of the past decade, according to the Icelandic Met Office. April, May and June were also unusually dry and warmer than usual.

Iceland’s breathtaking landscapes of glaciers and waterfalls, and an economy that’s largely dependent on natural resources, make the country particularly vulnerable to climate change. Its impact is seen everywhere.

The summer has been so hot and dry that the water level in the famous Red Lake near Reykjavik dropped from 140 centimeters to just 70 centimeters, according to the Met Office. The lake looks more like a bog now.

The drought also caused fewer salmon to swim up Iceland’s rivers. The National Association of Fisheries said salmon fishing slumped by a half compared to last summer.

Ögmundardóttir said the pace at which the country’s scenery has been changing is worrying, even by Icelandic standards.

“Nature here is really volatile and powerful and people just have to accept it if they want to live here… but the speed, it’s totally new and it’s enormous,” she said.

“When you see the glaciers retreat by dozens of meters a year, and see the vegetation change rapidly, we have invasive species now… That’s something new and it’s solely because of the rising temperature. So it’s tangible, it’s very visible,” she said.

Change does come quickly here. Skeiðará used to be one of the island’s biggest glacial rivers. Then, in 2009, it almost completely disappeared. The glacier feeding it retreated by two kilometers (1.2 miles) in the last two decades and forced the escaping water into a different direction.

“Over a period of about 10 days or a week, the Skeiðará river essentially dried up,” said Andrew Russell, a professor of physical geography at the UK’s Newcastle University who specializes in glacial systems.

The glaciers are shrinking because the amount of ice that melts away in the warmer summers is much higher than the ice that accumulates in the winters.

“You can think of that as spending money from your account,” said Halldór Björnsson, the lead weather and climate researcher at Icelandic Met Office. “If there’s less money flowing in, well, you will drain up your account.”

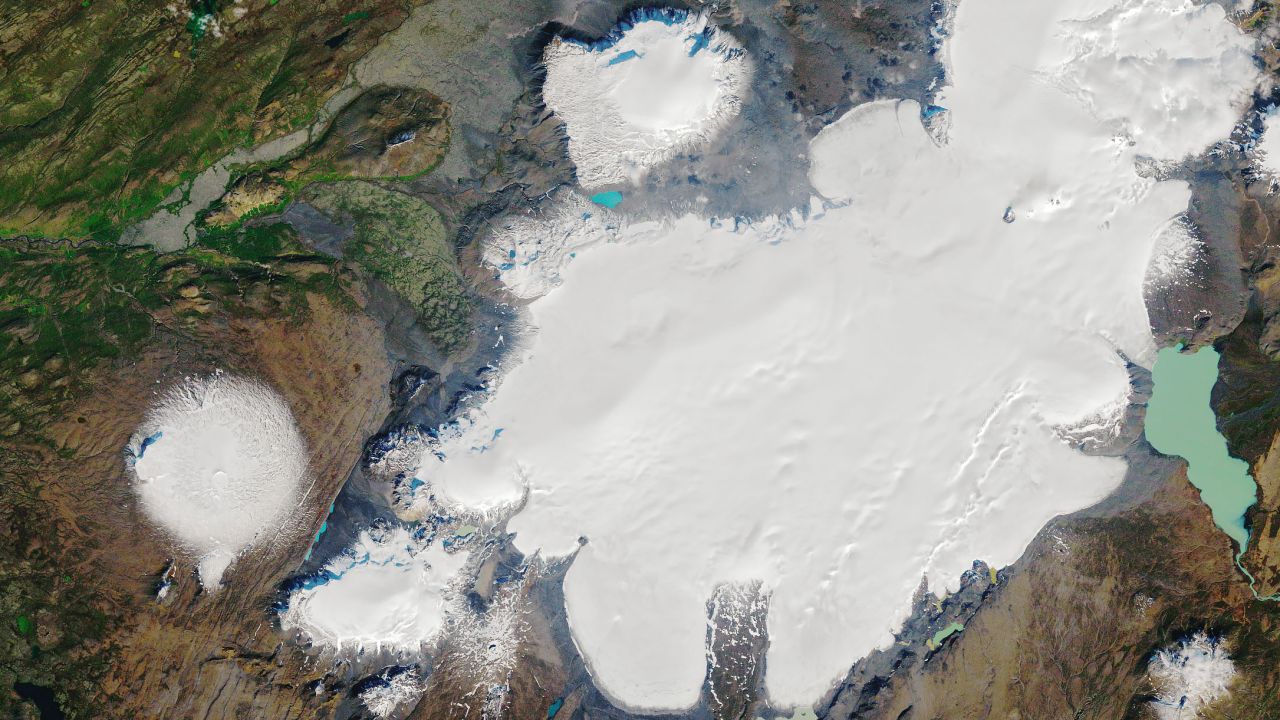

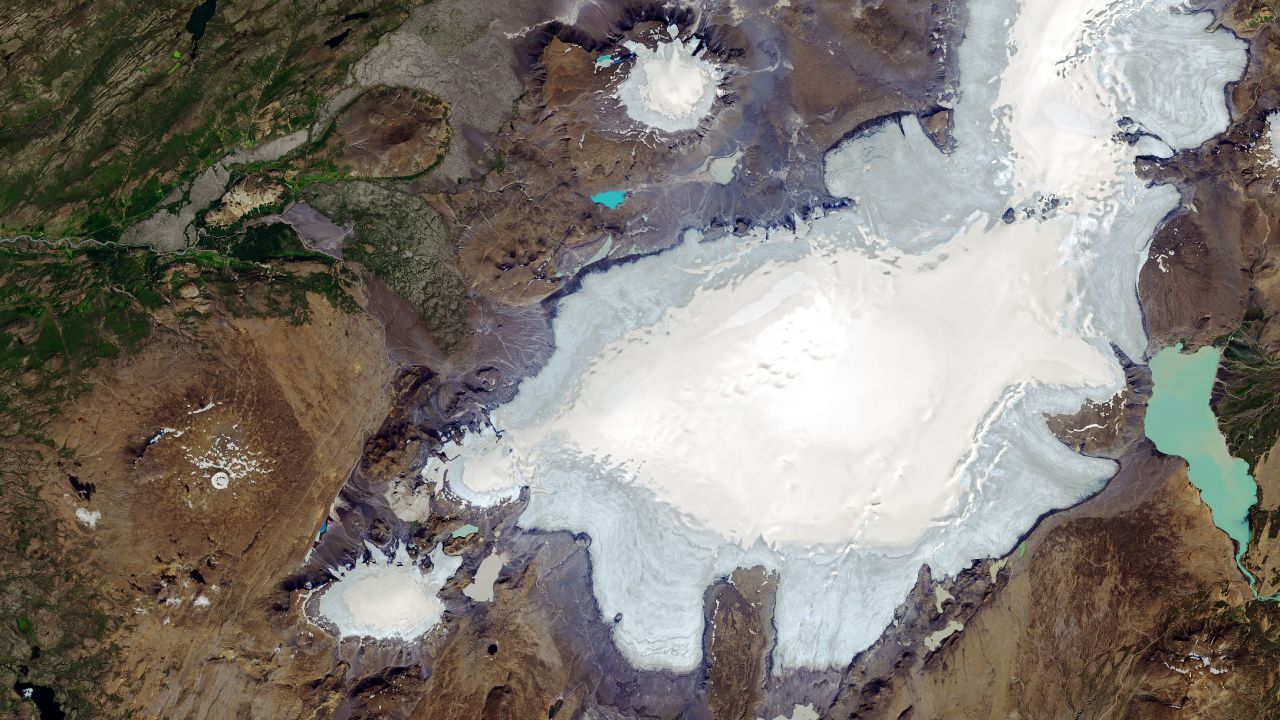

Historical maps show that glaciers have repeatedly shrunk and grown in Iceland. Since the late 19th century, when glaciation reached its most recent peak, they’ve retreated by 2,000 square kilometers. But 600 square kilometers disappeared since 2000.

“We’ve seen these things happen before, we had episodes where there were some glaciers retreating, but now they are happening on a much bigger scale,” Björnsson said.

Bulging ground

The melting glaciers have other consequences. The heavy ice masses weigh down the ground, compressing what’s underneath. When they melt away, the land rises and the sea level drops.

The ground in central Iceland is rising by more than three centimeters (1.1 inches) a year, according to scientists at the University of Iceland. This could cause major issues to infrastructure, especially in ports that become shallower and more difficult to dock ships in.

“When we talk about climate change, we almost always talk about sea level rises as a negative thing, so you would think ‘oh, they have sea level drop, good for them’… but that’s not the way it works,” Björnsson said.

“It turns out that having a sea level drop can be just as much of a problem as having a sea level rise.”

There’s more to worry about. The Earth’s crust, the outermost shell of the planet, is thin in Iceland, and geologists are left guessing what will happen to the volcanic activity underneath it if it bulges more.

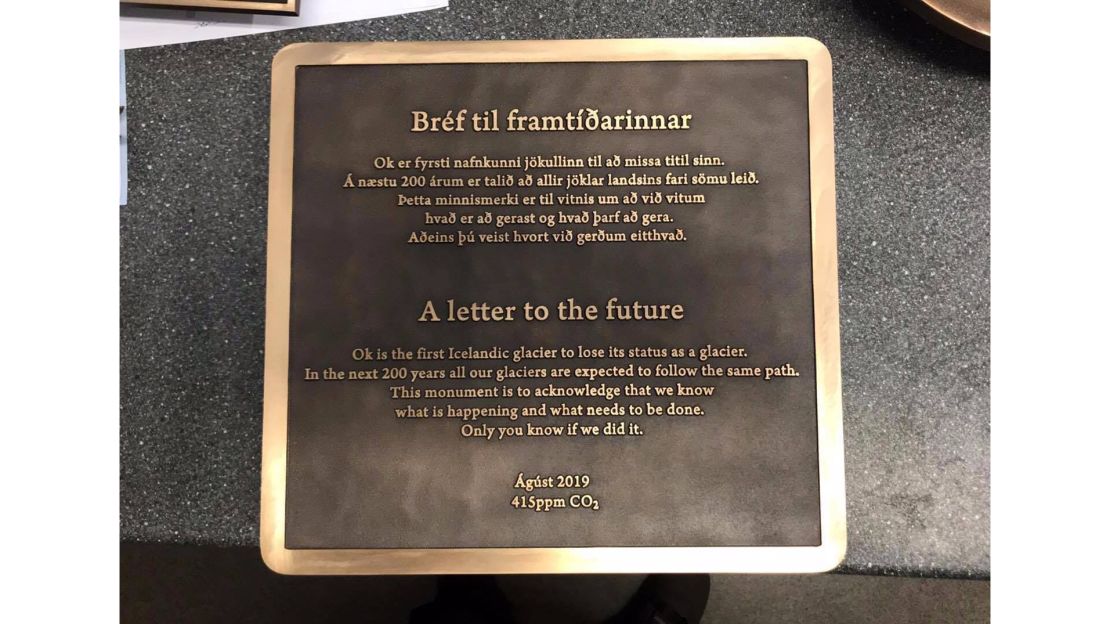

Skeiðará river isn’t the only Icelandic natural wonder that recently vanished because of climate change. Okjökull, a glacier in the east of the island, has melted in the past few years. There is now a plaque commemorating its existence. More glaciers are likely to follow.

There are some flipsides. Unlike many countries that struggle with the economic impact of climate change, Iceland could see some benefits – at least in the short term.

Research by the Agricultural University of Iceland has indicated the country could grow more cereals thanks to a warmer climate. The production of barley has already increased dramatically.

Iceland’s fishing industry has seen the impact too. After the turn of the century, mackerel escaping warming ocean waters started mass-migrating into Iceland’s territorial waters. Previously rare around the island, mackerel suddenly became abundant and Icelandic fishing boats wanted to take advantage of the shift.

When Reykjavik’s attempts to raise its official fishing quota fell flat, the country increased it unilaterally, sparking a multinational conflict dubbed the “Mackerel Wars.”

Iceland elected Katrín Jakobsdóttir, an environmentalist and leader of the Left-Green movement, as prime minister in 2017. Under her leadership, the country has adopted a plan to become carbon neutral before 2040.

The government has already increased carbon taxes by 50%, agreed to ban new diesel and gasoline cars from 2030 and put in place incentives to electrify its transport system.

It has also committed to plant more trees to mitigate the emissions that cannot be cut.

Tourists rushing in

But all that effort has one major problem.

Since its economic crisis in 2008, Iceland has become a major tourist destination. The number of overnight tourist stays in Iceland jumped from 2.7 million in 2008 to 8.5 million in 2018, according to the Icelandic statistical authority.

The sector contributed 8.5% to the country’s GDP and employs around 30,000 people during the peak summer season. With the country’s total population of just over 360,000, it’s a significant sector.

Iceland’s remote location means flights and cruise ships are the only way to bring tourists in.

“There are concerns about greenhouse gas emissions related to tourism, emissions related to flying (and) land transportation with all the rental cars… and there’s more and more concern about the pollution from the cruise ships,” said Lára Jóhannsdóttir, a professor of environment and natural resources at the University of Iceland. “There is concern that maybe we have too many tourists.”

Icelanders and tourists alike are watching the changing landscape.