Editor’s Note: CNN’s series often carry sponsorship originating from the countries and regions we profile. However, CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Our sponsorship policy.

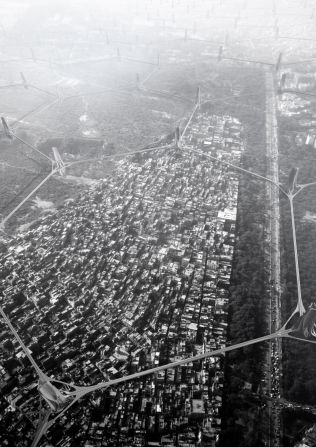

They look like something from a science fiction film: the industrial monoliths from “Blade Runner,” or perhaps the Martian pods in “War of the Worlds.” But in reality, these giant towers loom over the skyline of Delhi, in India, and land with benevolent intentions.

“The Smog Project,” designed by Dubai-based architecture firm Znera Space, is an ambitious proposal to clean the air in one of the world’s most-polluted cities.

Delhi’s citizens are on the frontlines of a smog crisis. During a particularly bad spell in late 2017, the quality of air was so poor that breathing it was equivalent to smoking 44 cigarettes a day.

World Health Organization data shows Indian cities dominate the top 20 most-polluted cities globally in terms of PM2.5 levels – atmospheric particles less than 0.0025mm (0.000098 inches) wide, the smallest and most dangerous size of airborne pollution.

Globally, the health implications of air pollution are profound. It caused about 4.2 million deaths in 2016, is linked to 3.2 million new diabetes cases annually and can impair cognitive ability, according to recent studies.

The Smog Project was shortlisted for a World Architecture Festival 2018 award in the “Experimental Future Project” category, for “proposals that challenge conventional thinking.”

“It’s a conversation starter,” says Najmus Chowdhry, principal architect for the concept. Chowdhry, raised in Chandigarh, about 150 miles north of Delhi, compares the nation’s capital to “a gas chamber,” but says politically “everyone is passing the buck.”

Curbing practices that cause smog – biomass burning, industry and transport emissions, among others – is a slow process that could take generations, he argues. And with further economic growth comes certain headwinds: car ownership in India is predicted to jump 775% by 2040, according to a 2016 International Energy Agency report, while, per KPMG, public transport’s share of the market is in decline.

“The situation at hand is so grave that it requires a top-down scheme,” Chowdhry adds.

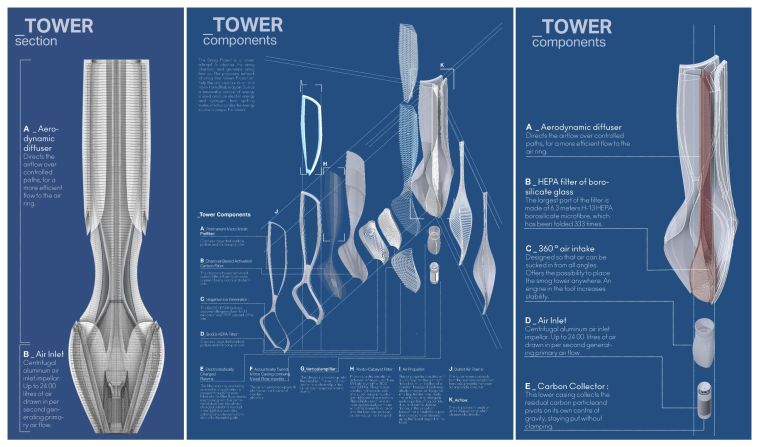

The Smog Project comprises a vast array of 328 feet-high air filtration pods, each capable of producing more than 353 million cubic feet of clean air per day, serving an area of 100 hectares, say its designers.

Inflows at the base of a tower suck in air and pass it through five stages of filtration – including charcoal-activated carbon, negative ion generators and electrostatically-charged plasma – to trap airborne particles. Air is forced upwards where it passes through a photo-catalyst filter to sterilize bacteria and viruses, before being released into the atmosphere.

Towers would be powered by solar hydrogen cells laid out in a hexagonal network of “sky bridges” between units – a nod to British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, who drafted the urban grid plans for an area of New Delhi in the early 20th century. The intention is for the network’s power needs to be self-sustaining.

As well as providing clean air, the repository of carbon particles captured could go on to find use in graphene, concrete, fertilizer, ink and water distillation, say the designers. (India has already seen innovations in this area, with Bangalore-based Graviky Labs producing Air Ink from collected carbon particles.)

Chowdhry describes it as a “feasible concept” and says a 15-20 meter-high (49-66 foot) prototype is at an “advanced conceptual level.”

The architect is in talks with AirLabs in Copenhagen, a startup specializing clean air technology, which Chowdhry says could produce simulation models for the design. But Znera is still looking for development funding. Chowdhry says as well as exploring opportunities in India, he will look to the UAE. He notes Dubai has experienced severe dust and sandstorms in recent years and could also utilize the technology.

“There are bodies in (the) Dubai government which actually encourage you to take such steps … to come up with such prototypes,” he says, adding talks have also taken place with Masdar City developer Mubadala, based in Abu Dhabi.

The design is notable for its scale, however it’s far from the only urban air filter in development. Dutch designer Daan Roosegarde’s 23-foot “Smog Free Tower” was unveiled at Beijing Design Week 2016, capable of cleaning approximately 25 million cubic feet of air a day. “CityTree” is a 13-foot by 10-foot moss-culture installation by Berlin-based Green City Solutions, which captures as much pollution as 275 trees, the company claims.

Sumit Sharma, director of the Earth Sciences and Climate Change Division at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) in New Delhi, describes Znera’s proposal as “commendable,” but offers caution.

“Considering the limitations of the technology in terms of its area coverage to treat widespread air pollution in the Delhi city, this is not the only solution we must rely upon,” he argues. “For long-term, wider-scale air-quality improvements, emission mitigation measures are required at the respective sources.”

Pratim Biswas, chair of the Department of Energy, Environment and Chemical Engineering at Washington University in St Louis, agrees. “Delhi needs to focus on deploying effective air pollution control technology at the source,” he wrote in an email to CNN.

Urban air filtration, he added, “would work in a neighborhood type concept – not a full megacity,” questioning the cost effectiveness of Znera’s design. Biswas didn’t dismiss urban air filters entirely though, describing them as “a secondary technique, and would be good for regional air cleaning (maybe around four or five skyscrapers).”

A localized approach is Znera’s initial aim, says Chowdhry, adding that doing so would still be a big step: “If we tackle one of the districts and see what the success rate is, I think that would basically quantify the success of the entire thing.”

But that is still a long way off. When pressed for a timeline, Chowdhry estimates a fully-functional prototype is still 2-3 years away.

Correction: The infographic in this article has been updated to correct the description of PM 10 particles.