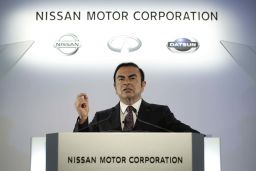

The downfall of Nissan Chairman Carlos Ghosn is a painful reminder that everyone needs a boss, even the most powerful captains of industry.

Ghosn, who was arrested on Monday over what Nissan called “significant acts of misconduct,” served as both the CEO and chairman of Nissan until last year. And he holds both those titles at Renault, the French auto giant. Shares of both companies plunged on the loss of their visionary leader.

When CEOs grab too much power, accountability and responsibility sometimes go out the window.

That lack of oversight can lead to fraud, such as with the demise of Enron under Kenneth Lay or Tyco under Dennis Kozlowski.

Other imperial CEOs, like Dick Fuld of Lehman Brothers, enabled reckless risk-taking that ruined their companies. John Stumpf failed to fix Wells Fargo’s toxic sales culture. And Jeff Immelt made a series of bad decisions that have come back to haunt General Electric.

“You need checks and balances,” said Ralph Walkling, founder of the Raj & Kamla Gupta Governance Institute at Drexel University.

“The board’s primary job is to hire and fire the CEO. And the board is run by the chairman. When those two roles are combined, it can present an awkward situation,” said Walkling.

Whistleblower complaint

Over his 40-year career, Ghosn became one of the most influential executives in the auto industry. He was the architect behind the global alliance of Nissan, Renault and Japan’s Mitsubishi. The three companies employ nearly half a million people in almost 200 countries.

Nissan said on Monday that following a whistleblower complaint it launched an investigation that found Ghosn and board member Greg Kelly had been underreporting Ghosn’s compensation. “Numerous other significant acts of misconduct have been uncovered, such as personal use of company assets,” Nissan said.

“Ultimate power can ultimately corrupt,” said Bill Klepper, a management professor at Columbia University.

Nissan acknowledged that problem on Monday.

“Some things should be corrected like over-concentration of power and corporate governance,” Nissan CEO Hiroto Saikawa said during a press conference.

Boards have long been pressured to break up the CEO and chairman roles. Keeping the roles together is tantamount to asking the president of the United States to also serve as the chief justice of the Supreme Court. The balance of power is slanted.

“If someone doesn’t feel accountable, they may engage in inappropriate acts. They feel invulnerable,” said Charles Elson, director of the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware.

‘Undetected flaws’

Plenty of corporate leaders have successfully held both titles. These powerful CEOs have been aided by the naming of respected lead independent directors charged with providing oversight.

For instance, Jamie Dimon is widely credited with steering JPMorgan Chase (JPM) through the financial crisis. Dimon, chairman and CEO for a dozen years, has turned JPMorgan into the biggest and perhaps most successful American big bank.

With Jeff Bezos as chairman and CEO, Amazon (AMZN) has become the most dominant company in Corporate America, and Bezos became the world’s richest person.

“Some imperial CEOs can lead very successfully,” said Walkling.

But he cautioned that the downside is also higher when there is that much power concentrated in one individual.

“The problem is if there are undetected flaws in your leader and you come upon allegations of misconduct, the company takes a hard fall,” said Walkling.

Consider the turmoil at Tesla (TSLA). Facing an SEC lawsuit for allegedly “false and misleading” statements, Elon Musk was forced to give up the chairman role.

And a series of scandals at Facebook (FB) has led to calls for chairman and CEO Mark Zuckerberg to relinquish some of his vast power. Zuckerberg has the majority of voting power at Facebook.

Imperial CEOs are less common

Even though Zuckerberg has resisted calls to separate his roles at Facebook, the trend in Corporate America is moving in that direction, albeit slowly.

Fifty-three percent of S&P 500 companies currently have separate CEO and chairs, according to management consulting firm Korn/Ferry. That’s up from 42% in 2011 and 26% in 2001.

And when imperial CEOs have stepped down, many companies are naming an independent chair. That’s what Wells Fargo (WFC) did when Stumpf left under pressure in 2016. Former Federal Reserve governor Elizabeth Duke became Wells Fargo’s chair this year.

Just 7% of S&P 500 companies that named a new CEO in 2017 combined the CEO and chair titles, according to executive search firm Spencer Stuart. That’s down from 30% in 2010.

Despite its stumbles under Immelt, GE (GE) still has not done so. Immelt’s immediate replacement John Flannery served as both chairman and CEO. Ditto for Larry Culp, who took over on October 1.

“A good CEO shouldn’t fear a separate chair,” Elson said. “They should welcome it.”

– CNN’s Jethro Mullen and Daniel Shane contributed to this report.