In its quest to become a global superpower, China has regularly become entangled in territorial disputes with its neighbors, butting up against international law.

But there’s one region on its radar with fewer rivals and where the rules are still being decided: the polar Arctic.

China sees an opportunity in the Arctic’s expansive sea of melting ice. Beijing has begun pushing for a greater stake in the region with a view to opening new trade routes, exploring for oil and gas and conducting research on climate change, experts say.

Geographically, China is nowhere near the Arctic Circle, which puts the Asian powerhouse at a major political disadvantage compared to eight countries that make up the Arctic Council, all of whom have territory inside the Arctic Circle.

Council members are divided on China’s growing interest in the region. Some smaller economies like Iceland and Norway see an opportunity, others with a strategic interest like Russia and Canada are growing wary.

China isn’t the only non-Arctic state interested in the region but it is by far the biggest, China and polar region expert Marc Lanteigne of Massey University in New Zealand told CNN.

In 2013 it joined India, South Korea, Japan and Singapore in gaining non-voting observer status on the Council.

“Overall, there’s been the acceptance that China is going to be a player there, but there is still some concern about the ambiguity to what China’s endgame is,” Lanteigne said.

Polar silk road

In January, Beijing published its first Arctic strategy white paper, claiming a vested interest in the region while attempting to allay fears over its territorial ambitions.

It defines itself as a “near-Arctic state” in the document, saying environmental changes in the Arctic have a “direct impact on China’s climate system and ecological environment.”

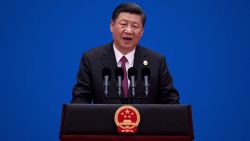

The white paper details Beijing’s plans for a “Polar Silk Road” as part of its multi-trillion-dollar Belt and Road infrastructure program, a signature policy of President Xi Jinping whose government has spent big to build vast trade corridors across the world.

While the Belt and Road initiative has drawn criticism in the West due to concerns that China is ensnaring developing countries in debt, Lanteigne says it’s welcomed by some of the smaller Arctic players keen on building economic ties with Beijing.

“It has excited quite a few of the Nordic states who see the possibility of expanded Chinese sea traffic and potentially new ports,” Lanteigne said.

The idea of a mutually beneficial partnership is exactly the reassuring message China sought to drive home in its Arctic policy, with repeated references to “cooperation.”

It’s a stark contrast to Arctic Council concerns before China’s admission, when members feared it could seek to repeat its South China Sea territorial grab in the Arctic Circle.

Beijing claims an enormous swath of territory in the South China Sea, and has created heavily fortified artificial islands to help assert its position in the Spratly and Paracel island chains.

In comparison, the situation in the Arctic is relatively peaceful, according to experts, with no serious territorial disputes. And the Arctic states are eager to keep it that way.

‘Brimming with economic potential’

Beijing claims the main reason for its interest in the Arctic is scientific research.

In the white paper, it detailed a desire to investigate the effects of climate change to “resolve global environmental issues.”

But skeptics have argued that China’s Arctic ambitions are largely fueled by the economic and political appeal of dominating a resource-rich area.

It is estimated that the Arctic may hold nearly one-third of the world’s natural gas and 13% of global oil reserves, according to a report by Rachael Gosnell at the University of Maryland.

And as rising temperatures melt the region’s ice, shipping routes that were once impassible are now an attractive and feasible alternative for the world’s second-largest economy.

“The Arctic is brimming with economic potential,” said Gosnell, who estimates that the annual economy of the region exceeds $450 billion.

According to NASA, some global climate models predict the Arctic will be ice-free during the summer months by the middle of this century, likely making its waters an important shipping route.

“China really wants to put itself in a position whereby, should there be some kind of scramble or push for Arctic resources, China would be very well placed to take advantage of that,” said Lanteigne, the polar region expert.

To secure that position, it is strengthening its Arctic capabilities. In September, China launched a second icebreaker known as Xue Long 2, or Snow Dragon 2, with an expedition scheduled for the first half of 2019, according to state-run media.

The newly minted vessel is the first Chinese-built icebreaker. The China State Shipbuilding Corporation claims it will be more capable of cutting through ice and carrying out advanced research than its foreign-built predecessor.

Washington’s loss, Beijing’s gain

China has been quick to recognize the importance of investing in the Arctic at a time when there are few participants and even fewer laws, so that it can eventually restructure Arctic governance in its favor, said Harriet Moynihan, associate fellow at the UK think tank Chatham House.

China’s increasing involvement in the Arctic Circle has also coincided with a growing lack of interest from Washington.

Former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson moved to eliminate a special envoy and representative for the Arctic region in 2017, as climate change dropped down the list of priorities for the Trump administration.

After World War II, the United States had seven icebreakers in its fleet. In 2018 only two functioning icebreakers remain, one of which is a heavy-duty vessel overdue for an update.

The Obama administration pursued an ambitious Arctic strategy to ensure the US remained a strong power in regional affairs, including plans to replace the heavy icebreaker by 2020.

But it’s unclear where the US now stands on those plans. The US Coast Guard, which runs the icebreakers, faces significant budget cuts as more and more funding is reconsidered for border security.

“Because of the fact that the Arctic is not a priority for the Trump government, this has allowed China to take the steering wheel and accelerate their own Arctic policies,” Lanteigne said.

Russia is arguably the most active Arctic state, with a fleet of more than 40 icebreakers, and it is reluctant to allow non-Arctic countries to develop the region.

But facing mounting Western sanctions, Moscow’s attitude toward China has warmed considerably. “Russia realized that China was one of the few countries left that could really help with Siberian development,” Lanteigne said.

“The two countries have cooperated in a number of Arctic ventures, including a liquefied natural gas project.”

With large parts of the Arctic still difficult for China to reach, it remains less important to Beijing than investments in other parts of the world, such as Africa and South Asia.

But China’s presence in the far north is only likely to grow – whether the Arctic states are pleased about it or not.