Meimei Xu grew up in Illinois, Florida and Georgia. But that didn’t stop people from asking her, “Where are you from?”

The 19-year-old says growing up Asian American hasn’t been easy. When she was in grade school there were classmates who made hurtful comments. They told her Chinese food was strange and one of them even told her Chinese girls aren’t attractive.

But she doesn’t want those experiences defining her. “I would rather define my own existence,” she says.

The recent Atlanta-area spa shootings that left eight people dead, including six Asian women, are shining a spotlight on the struggles of Asian American communities across the US. And experts are warning how the rise in anti-Asian violence can leave lasting mental health repercussions.

A study by the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino, shows that anti-Asian hate crimes in 16 of America’s largest cities increased 149% in 2020. The first spike occurred in March and April amidst a rise in Covid-19 cases and negative stereotyping of Asians relating to the pandemic.

But it’s not just the immediate effect of these hate crimes that people have to worry about. One psychiatrist says anti-Asian racism can have far-reaching mental health repercussions.

In an article in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. James H. Lee, a first-year psychiatry resident at University of Washington School of Medicine, said that if physicians don’t address the issue with patients who have experienced racism they risk leaving them to deal with mental illness on their own.

“I think that one of the consequences of this racism is going to be a lot of anxiety and depression,” Lee said in an interview with UW Medicine. “And fear and trauma. I don’t want to miss those. I don’t want our healthcare system to miss those. And I think that the way we’re currently operating we could. We could let a lot of patients fall (through) the cracks.”

A Pew Research study published in July 2020 found that 58% of Asian-Americans felt anti-Asian racism had worsened since the beginning of the pandemic. And 26% feared that someone might threaten or physically attack them.

Concerns over mental health are especially important when dealing with children and young adults. CNN spoke to high school and college students about the prejudice they’ve faced growing up Asian American in the US.

What if they were my grandparents?

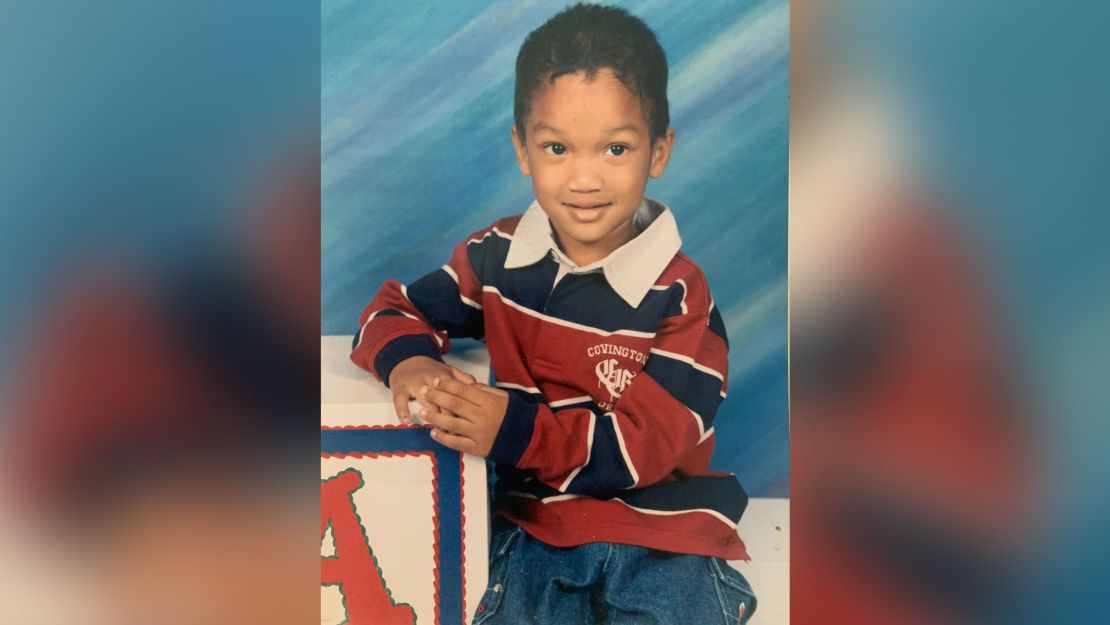

Javon Huynh, 20, says he and his siblings were the only Black Vietnamese Americans growing up in his Georgia hometown.

He especially remembers one incident when he was six years old.

“I was in the office waiting for my mom to come get me. It was really late, so the lady at the front office and my teacher tried calling her and one of them had a hard time pronouncing her last name. So they started laughing and making jokes about it. And I just remember in my head being mad and upset,” Huynh says. “They may have thought there is no harm in a little joke and it wasn’t that serious, but it’s my name, my heritage. My name has meaning and a story behind it,” he adds.

Huynh says his family celebrates both Asian and American culture. They celebrate Lunar New Year but also enjoy celebrating Thanksgiving. But they try to add some Vietnamese flavor to their holiday meals by having fried rice and egg rolls alongside turkey for Thanksgiving and Easter.

Language and cultural differences make it harder for some Asian families when they emigrate. And Huynh feels his mother and aunt had a harder experience when they were growing up.

“They had to learn English and help translate to Vietnamese for my grandparents. It must have been so difficult for them having to learn things like how to buy a house or a car or find a job because it wasn’t easy back in the 80’s trying to get or apply for those things,” he says.

Huynh feels the recent spate of anti-Asian hate crimes has been very unnerving. He is very close to his grandparents and says these attacks worry him.

“When I see older Asians getting attacked, I can’t help thinking ‘What if they were my grandparents?’” he says. He adds that many Asians don’t speak up about these problems not because they don’t care, but because they are scared and want to avoid conflict.

Huynh says negative incidents definitely made it harder for him to fit in as he grew up, especially when people would make him feel that being different was a bad thing. “It also made me more closed off instead of embracing who I am,” he says.

But once he got to travel outside his small town he finally realized he was not alone.

Huynh says he really found his niche when he joined band in sixth grade. Band became his “happy place” and that’s where he met lifelong friends. He credits his high school band director with really helping him and becoming like “a father figure I never had.”

That’s why Huynh says he wants to become a teacher. “I enjoy working with kids and want to help be a voice for them, especially kids with different cultural backgrounds. I want to have an impact on their lives,” Huynh adds.

Fears of being stereotyped

Meimei Xu says the racial prejudice was most difficult to face when she was in elementary school. “Some of my classmates would pull back their eyes into slits and imitate the language,” Xu says.

“In middle school, I often heard the phrase, ‘Of course she’s smart, she’s Asian,’” Xu says, recalling that sometimes she felt ashamed of playing the violin and doing well in certain subjects because they seemed stereotypically Chinese.

But as she grew older, Xu says, the discrimination has been more subtle.

Xu says her family also celebrates both Asian and American culture: Eating a big potluck meal with other Chinese families during Lunar New Year and having Turkey during Thanksgiving. But her parents have helped her stay connected to her roots as well.

“I visit my relatives in China every two or three years. We usually stay for a few weeks, spending a few days in different cities since all our relatives live in different places,” Xu says.

Xu says as she grew older she fostered strong connections in writing groups. “I felt most welcome in environments that did not put a strong emphasis on racial divides,” she says.

She hopes to become a journalist and perhaps also go to law school and work in government one day.

“The negative incidents of racial discrimination in my childhood are no longer something that I see as an integral or even influential part of my growing up. I do not want to give power to other people’s negative perceptions of me. I see my growing up as a process of me finding my own strength, on my own terms and in my own time,” she adds.

A humiliating experience at summer camp

Tiffany Pham, 17, says sometimes when Asian Americans face discrimination, they’ve been “conditioned to just sit passively and endure it, rather than sticking up for ourselves or fighting back.”

“Part of it lies in the linguistic barrier, part of it lies in fear of being ostracized even further,” says Pham, who grew up in Georgia.

She says she lived in a community that was very diverse with many immigrant families, including Hispanic and Black families. And they all celebrated each other’s cultures.

“We went to a Buddhist temple every Sunday. It was a place where I could bond with kids who looked like me, and I could relate to,” she says. But during break at Sunday school, she would speak English “and talk about American things.”

Pham says her most humiliating experience was probably during a summer camp trip.

“A boy was slanting his eyes and making racist jokes in a horrible, mocking Chinese accent. A couple of the kids sitting with him began to laugh too. I remember that I wanted to crawl into a hole at that time. I begged my friend to let me borrow her earbuds so I didn’t have to listen to the taunting. No one really stood up or said anything back to him,” she says.

The experience was like a wake-up call. “I realized that this would be an experience that I’d come to encounter more often as I grew up,” Pham adds.

She says a lot of Asian American children are conditioned to think that humiliating jokes and comments are something that happens and “not worth discussing.”

But things got better for her in middle school. When she ran for student council one classmate made a derogatory comment. “But I ended up winning the election,” she says. “In a way, it sort of solidified my acceptance into American culture. My classmates didn’t perceive me in a discriminatory or prejudiced way because I was Asian.”