Japan and South Korea are engaged in a heated military dispute that analysts say could damage the already tenuous geopolitical situation in northeast Asia if the two sides do not reach a resolution.

The spat began December 20 after an encounter between a Japanese plane, which Tokyo said was collecting intelligence, and a South Korean destroyer, which Seoul said was on a humanitarian mission.

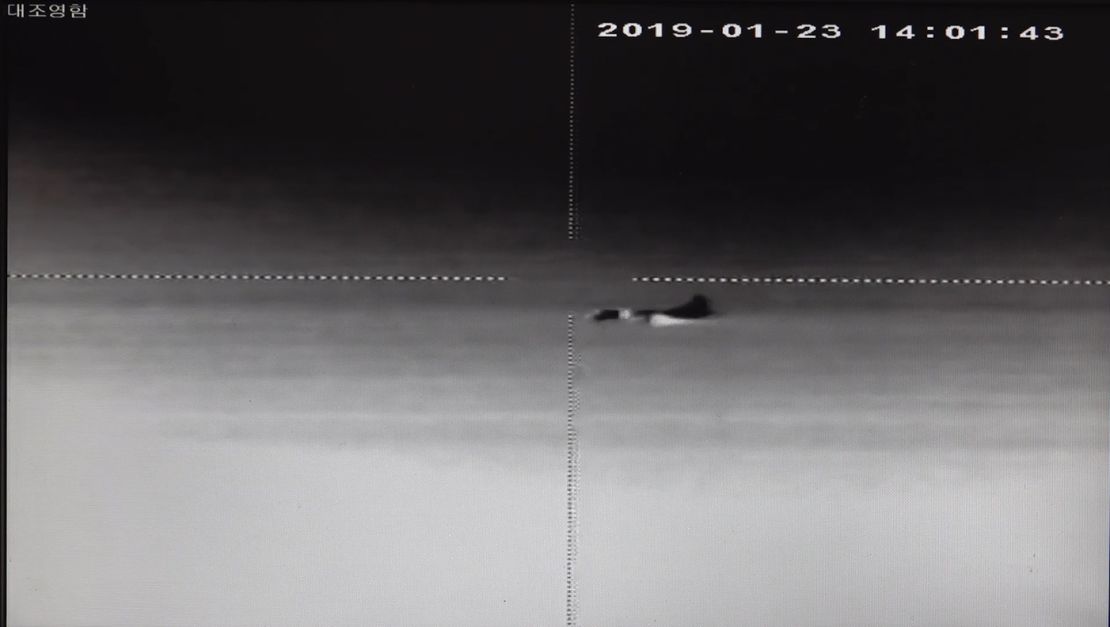

Both sides disagree on what happened next – the Japanese said the South Koreans targeted their aircraft with missile-targeting radar, while the South Koreans said the Japanese plane was flying dangerously low and that the radar “was not intended to trace any Japanese-controlled aircraft.”

The disagreement has quickly escalated, bringing to the fore historical disputes previously on the back-burner and – in turn – threatening the region’s stability.

“East Asian geopolitics has been shaken loose and is now unsettled,” said Van Jackson, a former US Department of Defense official specializing in the Asia-Pacific.

“China is seeking to push out the US, North Korea has pulled a jiujitsu move by using summit diplomacy to solidify its status as a nuclear state even as the ostensible purpose is to denuclearize Pyongyang, and the future of the US in the region is less certain now than any time since the 1970s.

“Amid all this tumult, suppressed animosities are started to crack through the veneer of regional stability.”

A marriage of convenience

South Korea and Japan are historical adversaries locked in a marriage of convenience, which makes for a complex partnership. Their relationship is still very much colored by the legacy of imperial Japan’s occupation and colonization of the Korean Peninsula in the first half of the 20th century.

This revived tension comes at a terrible time for the United States – the Trump administration is currently preparing for its second summit with North Korea, while also inching towards a key deadline in trade talks with China.

Shortly after the initial incident, Japan and South Korea held working-level meetings to try to resolve the issue behind closed doors.

It appears to not have worked – and neither side is buying the other’s explanation.

Japan released video of the incident from its perspective on December 28. South Korea released its own video on January 4. Each accused the other of misleading the public and distorting the facts.

Japan has conducted three other flybys over South Korean ships this month – one last week, one on Tuesday and another Wednesday. Seoul publicly condemned the latest as a “clearly provocative act” against a “partner country.”

Lawmaker Song Young-gil, from South Korea’s ruling Democratic Party, has even gone so far as to suggest Seoul pull out of its General Security of Military Information Agreement, a pact allowing the two countries to share sensitive intelligence.

Jonathan Berkshire Miller, an analyst at the Tokyo-based Japan Institute for International Affairs, believes historical enmity contributed to the sudden deterioration of relations.

“The context is key,” he said.

Historical adversaries

Despite their historical differences, South Korea and Japan share plenty of surface similarities. They’re both vibrant democracies with developed economies. Geopolitically, they are both US allies; they both want a denuclearized North Korea; they both support free trade; and they both view China’s rise with trepidation.

But history looms large, and the Japanese occupation and colonization of Korea – when many Koreans were brutalized, murdered and enslaved – is still a highly emotional issue that defines their relationship.

South Korea and Japan signed a treaty in 1965 that normalized relations between the two countries and was supposed to settle most of the wartime issues.

But South Korea was a military dictatorship at the time, and many Koreans felt the deal was unfair – and today are still fighting against it.

The two countries are still locked in heated debate over statues depicting “comfort women” – Korean women forced into providing sexual services for Japanese soldiers – and recent decisions by South Korea’s Supreme Court allowing citizens to sue Japanese corporations for reparations for forced labor.

Japan contends both issues were settled by the treaty.

Even further, they have been in a heated dispute for more than 50 years over ownership of a group of islands called Dokdo in Korean and Takeshima in Japanese.

Despite all this, military-to-military relations between Japan and South Korea often appeared largely unaffected by the ebbs and flows of political disagreements, said Miller, the analyst at the Japan Institute for International Affairs.

“That was the one area that was kind of quarantined or immunized before,” he said. “It wasn’t always perfect … but it was one that they both agreed was for the better good for the both of them.”

Alliance maintenance

Japan and South Korea’s foreign ministers met on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Wednesday to discuss the issue, but their meeting ended with statements that did not appear to resolve anything.

Not with them at Davos was their shared treaty ally, the Untied States, which typically would help mediate the dispute. President Donald Trump canceled his trip to Davos to deal with the US government shutdown.

Some have accused the White House of not placing enough importance on alliance coordination and management. Former Defense Secretary James Mattis pointed to that as a key disagreement between himself and the President in his resignation letter.

“Our strength as a nation is inextricably linked to the strength of our unique and comprehensive system of alliances and partnerships,” Mattis wrote.

“While the US remains the indispensable nation in the free world, we cannot protect our interests or serve that role effectively without maintaining strong alliances and showing respect to those allies.”

Analysts like Jackson, the former Defense Department official, worry that the current spat is a manifestation of declining US leadership, and will play into the hands of North Korea and China – two countries that have historically sought to diminish US influence in the region by causing rifts between Washington and its allies.

“What we’re seeing lately is a return to history in some sense – the two countries never fully reconciled when they normalized relations in 1965, and put a lot of conflicts of interest on the back burner in the name of cooperation with the US,” Jackson said.

“If something doesn’t change, I expect some kind of serious crisis to break out at some point, unfortunately.”

CNN’s Jake Kwon in Seoul and Yoko Wakatsuki in Tokyo contributed to this report