Sen. Chris Coons is not running for president.

At this point, that any Senate Democrat would say this publicly seems like news: Should the nine incumbent Senate Democrats already running, exploring a run, on a listening tour or considering a bid actually all get into the race, it would mark the most from the chamber since before at least 1960, according to the Senate Historical Office.

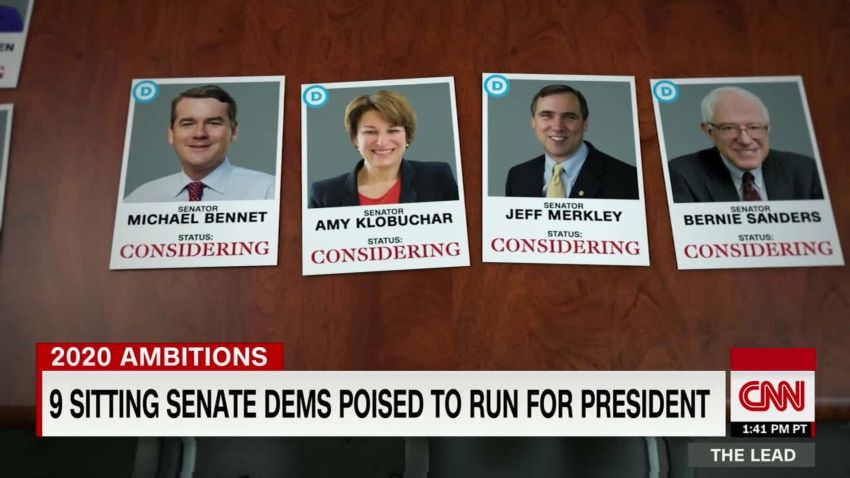

Sens. Cory Booker and Kamala Harris are already in the race. Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar, who both have events billed as “big announcements” this weekend, are expected to officially join in a matter of days. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand formed an exploratory committee, Sen. Sherrod Brown is on a listening tour and Sens. Michael Bennet, Jeff Merkley and Bernie Sanders, an independent who caucuses with Democrats, are actively considering runs.

That leaves 38 members of the caucus attempting to navigate the policy push and pull inside the party and natural tensions that come with colleagues entering the national spotlight.

“Whether they like it or not,” Coons, of Delaware, said with a grin when asked if he was briefing colleagues on his views and work on foreign policy, a central issue of his work in the Senate. “We can’t afford to stop paying attention to the world for the next 18 months while the primary and the general election rolls out.”

It’s a common theme among Senate Democrats who are not eyeing the White House in 2020: influence the national policy debate on the campaign stage to the degree possible, support the candidates broadly (though most aren’t planning to endorse any time soon, if at all), stay in the fight in Washington, and, perhaps most importantly, keep the peace – at least for as long as possible.

Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaii said to some degree, the sheer number of colleagues running creates a better situation for those who aren’t.

“All my friends are running for president,” Schatz said in an interview. “And I think it’s sort of freeing.”

Schatz said he planned to stay out of the primary but noted that the current field represented “a good problem to have – you have real competition.”

But staying away from endorsements doesn’t mean staying away from attempting to influence the debate happening inside the primary. Schatz said he viewed his role over the next year-plus as doing the legislative work on issues like climate change and expanding Medicaid and college affordability that could help one of his colleagues, should they win in 2020, hit the ground running.

“I think they’re very happy to have some sort of legislative heft behind what they’re talking about on the campaign trail,” Schatz said of his colleagues. “But if you’re spending most of your time in Iowa and South Carolina and Nevada and California and everywhere else, it’s for difficult to do the kind of boring work of putting together legislation and that’s what I’m for.”

There’s also the reality that even in divided government, with sharp disagreements between Democrats and the White House on foreign policy and a raft of nominees soon to be heading to the Senate floor, there’s a need for senators to actually be in Washington to push back from the Senate minority.

“First, it’s important for a few of us to stay here in the United States Senate because there are some really important fights that are going to happen here,” Sen. Chris Murphy said in an interview.

Murphy has publicly and privately pushed potential candidates to embrace a progressive foreign policy that he defines as both internationalist, but not reliant on the US military to serve “as the tip of the spear in terms of how we protect our interests abroad.”

It’s a position that had an early test in just the last week on the Senate floor, where an amendment opposing President Trump’s withdrawal of US forces from Syria and Afghanistan, was opposed by six of the 2020 hopefuls.

“I think that vote was interesting in that our party was still very split on whether we support using the military overseas to try and solve complex political problems or not,” Murphy said of a vote. “But it is instructive that anybody who wants to be on the ballot nationally in 2020 believes that the better path is to support the United States that is less enthusiastic about using our military in places like Syria.”

The amendment vote put the six 2020 hopefuls on the opposite side of more than 20 of their colleagues, including Coons and Sen. Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire, another Democrat who has become a leading bipartisan voice for the caucus on foreign policy issues, and on the losing side of the actual vote, which ended up with a tally of 68-23.

Shaheen said the vote was an example that “in the foreign policy arena, there is a lot of bipartisan agreement,” and when asked, said she was happy to brief colleagues on her views if they requested them. But overall “these are issues that we continue to work on because they are critical to this country.”

Though she hails from a critical early primary state, Shaheen said she won’t make an endorsement, but is keen on the opportunity the state’s role has in elevating an issue with candidates she has served as a key player on in Washington: treatment of the opioid epidemic that has ravaged the state.

“Having an opportunity to have so many people who are running for president who will go through this state who will hear the challenges that we’re facing – I think that’s good for making sure we can continue to make progress on this horrible epidemic that’s affected so many individuals and families,” Shaheen said.

For all of the policy goals and proclaimed friendships, there is also a clear reality that will at some point hit the forefront of the race – it’s not always going to be friendly or collegial on the campaign trail.

“Some of these people running against each other are genuinely close friends,” Schatz said. “It’s not one of those, Senate friendship where they say, ‘my friend from so and so’ but they really don’t mean it. I think everybody knows that, just statistically speaking, if you’re running among seven or eight Senate colleagues a handful of governors and mayors and others, the chances of you returning to the Senate are very, very high. And so it behooves anybody who’s running to just be nice.”

Murphy said there is an early emphasis between those running and those who aren’t about keeping things as above board as possible.

“There are just going to be a lot conversations happening between friends who are also running for president about how to make sure that it doesn’t get any uglier than it has to be,” Murphy said.

And how ugly does it have to be?

“Ultimately as you get closer to decision time, candidates have to draw distinctions, they have to draw contrasts,” Murphy said. “That doesn’t have to happen until later in the game, but at that point there’s no way for that not to ultimately cause a few bad feelings. That’s the nature of how this business works.”