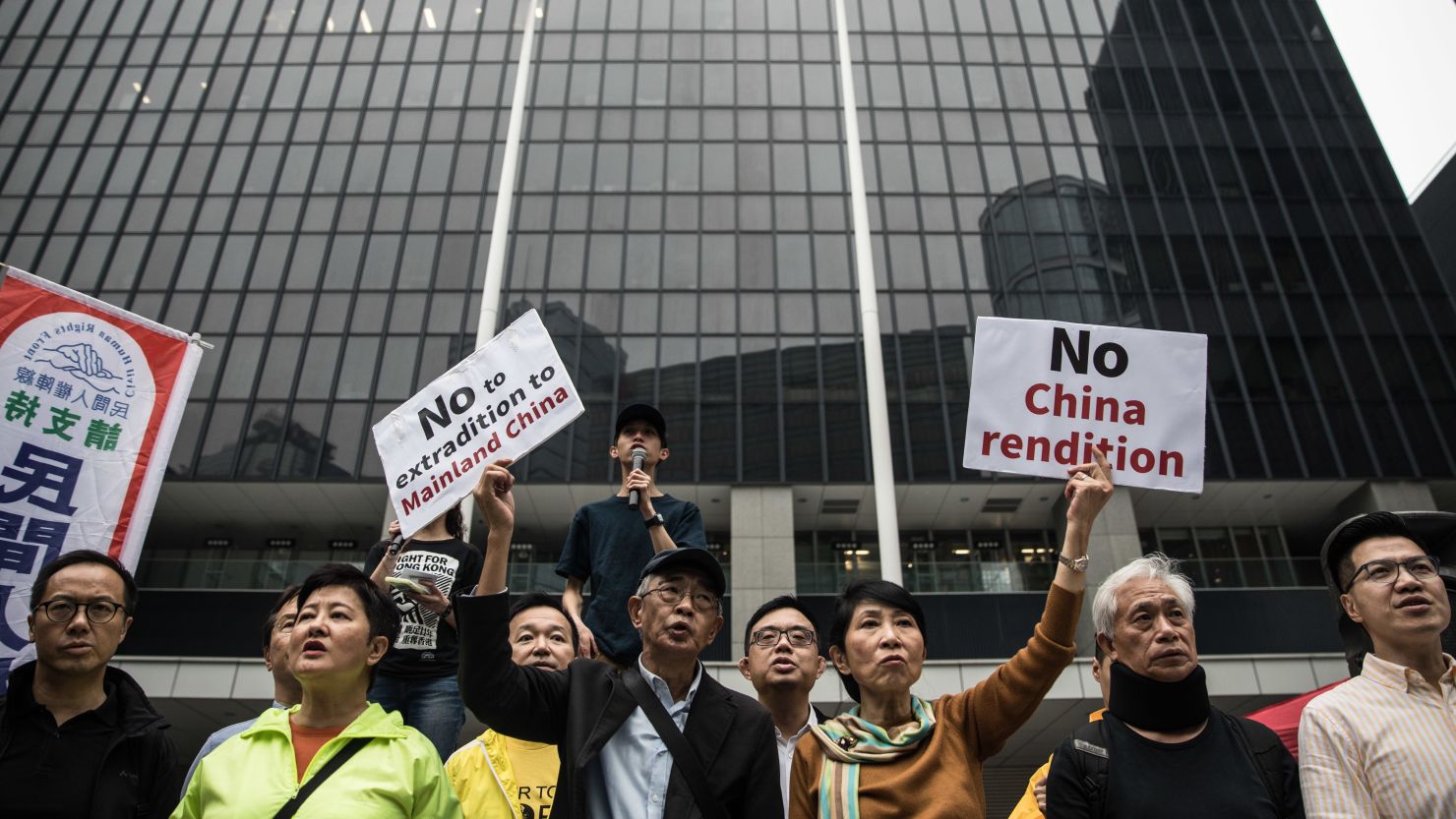

The UK government has expressed concern over a new extradition law between Hong Kong and China, as British lawmakers warned the move could see pro-democracy activists, journalists, and foreign business owners surrendered to Chinese authorities.

British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt said he had “formally lodged our initial concerns” with the Hong Kong government, he said in a letter to Chris Patten, the city’s last colonial governor.

“We have made it clear to the Chinese and Hong Kong Special Administrative Regions that it is vital that Hong Kong enjoys, and is seen to enjoy, the full measure of its high degree of autonomy and rule of law as set out in the Joint Declaration and enshrined in the Basic Law. … I can assure you that I, and my department, will continue to closely monitor developments in Hong Kong,” Hunt said, according to a copy of the letter Patten shared with UK-based pressure group Hong Kong Watch.

“It is clear that the relatively short formal consultation process has not been sufficient to capture the wide-ranging views on this important topic.

While Hong Kong is a special administrative region of China, the city operates its own legal and political system, and citizens enjoy a number of freedoms not protected on the mainland. At present, Hong Kong does not have an extradition law with China, Taiwan or Macau, a situation officials in the city say has created loopholes preventing criminals from being brought to justice.

Fear that the law will allow dissidents and pro-democracy activists to be bundled over the border to China has dogged the bill since it was first suggested, however.

Business groups too have expressed concerns, prompting the government to remove nine economic crimes from the list of potentially extraditable offenses. The government also changed the minimum severity of offense from those carrying one year in prison to three.

In a statement responding to those changes, the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) said members continued “to have serious concerns about the revised proposal.”

“Those concerns flow primarily from the fact that the new arrangements could be used for rendition from Hong Kong to a number of jurisdictions with criminal procedure systems very different from that of Hong Kong – which provides strong protections for the legitimate rights of defendants – without the opportunity for public and legislative scrutiny of the fairness of those systems and the specific safeguards that should be sought in cases originating from them,” the AmCham statement said.

“We strongly believe that the proposed arrangements will reduce the appeal of Hong Kong to international companies considering Hong Kong as a base for regional operations.”

Responding to reporter’s questions about the law last month, Hong Kong Secretary for Security John Lee said the extradition law was part of the city’s “international commitment to fight organized crime.”

He said the foreign business community should support the effort, which “will benefit (the) business environment.”

“If the accusation is that somebody may unwittingly become a political offender, then I have said repeatedly that the law at present, under our Fugitive Offenders Ordinance, has clearly stated that this will not be possible,” Lee added.

“There is a provision to say that no matter how you purport that offense to be, if it relates to political opinion, religion, nationality or ethnicity, then it will not be surrenderable.”

AmCham’s statement is part of a growing chorus of condemnation of the law from multiple quarters. Critics of the law point to past situations where people have been snatched in Hong Kong and transported to China to face trial, including multiple booksellers and Chinese businessman Xiao Jianhua.

Last week, the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) said the new law could enable the Chinese government to extradite reporters critical of Beijing, saying it would “not only threaten the safety of journalists but also have a chilling effect on the freedom of expression in Hong Kong.”

“Over the years, numerous journalists have been charged or harassed by mainland authorities with criminal allegations covered by the (law),” it said.

“The (law) will make it possible for mainland authorities to get hold of journalists in Hong Kong (on) all kinds of unfounded charges. This sword hanging over journalists will muzzle both the journalists and the whistleblowers, bringing an end to the limited freedom of speech that Hong Kong still enjoys.”

The Hong Kong Bar Association has also criticized the new law, and questioned the government’s assertion that there were loopholes in the city’s current arrangements.