Evidence of Viking settlements in Greenland conjures images of the intrepid Norse that settled there amid freezing temperatures centuries ago, between 985 and 1450. But as evidence grows to the contrary, it seems like Vikings may have been a little more comfortable, temperature-wise, than we thought.

Today, Vikings are depicted in shows and movies wrapped in furs to keep warm. And previously, researchers have clashed over what Greenland’s climate was like during the time of the Vikings.

But new study that reconstructs Greenland’s climate timeline for the last 3,000 years reveals that the average was more like 50 degrees Fahrenheit – which is a nice, normal day during southern Greenland’s summer today. The study was published Wednesday in the journal Geology.

“There’s been a long-standing sort of legend, that the Vikings were able to settle in Greenland thanks to a warming climate,” said Yarrow Axford in an email, senior study author and associate professor at Northwestern University’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. “And also that the Viking colonies on Greenland collapsed when climate cooled off again. There were hints in previous work by other groups that it was indeed warm when the Vikings were there, but more recently some studies from other, nearby areas have suggested the opposite.”

The biggest issue standing in the way of an answer to this “climate mystery” was a lack of paleoclimate data, Axford said.

Everett Lasher, a Ph.D. candidate at Northwestern University, was working on research for his dissertation about how Greenland’s climate has changed over thousands of years since the end of the last ice age, about 11,000 years ago.

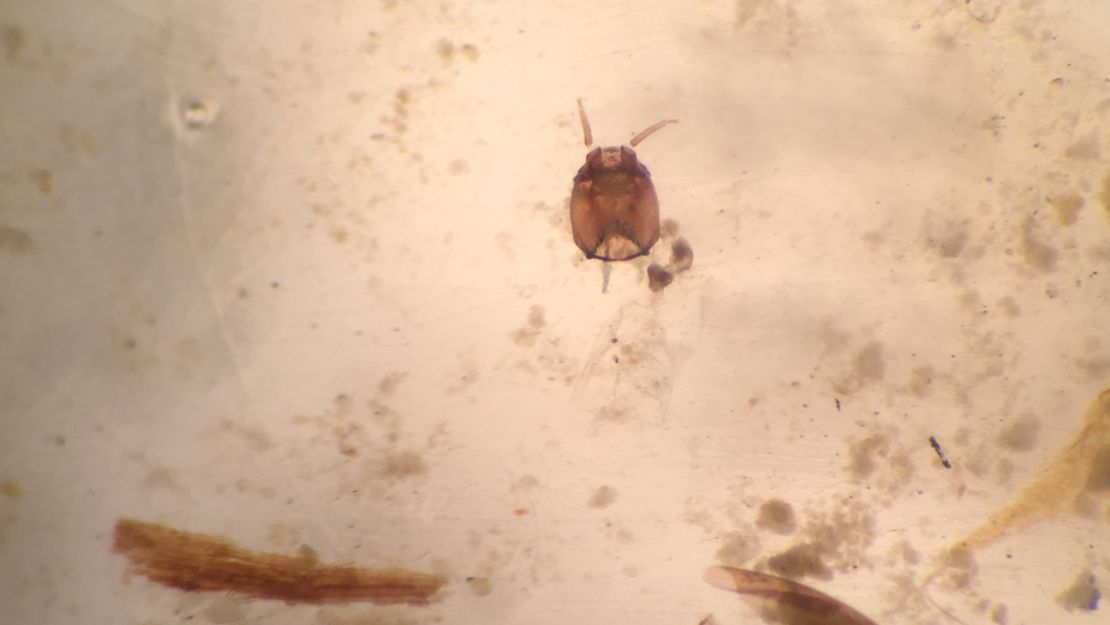

Most of the Arctic climate change was due to changes in Earth’s orbit in relation to the sun during this time period, Lasher said in an email. Lasher worked on a technique to reconstruct Arctic climate change by looking at the oxygen isotopes of insects called chironomids that were preserved in the lake sediments of areas in Greenland that are free of ice. Collecting these lake sediment cores is similar to the ice cores collected in Antarctica to study climate change.

“The oxygen isotopes we measure from the chironomids record past lake water isotopes in which the bugs grew, and that lake water comes from precipitation falling over the lake,” Lasher said. “The oxygen isotopes in precipitation are partly controlled by temperature, so we examined the change in oxygen isotopes through time to infer how temperature might have changed. Yarrow and I thought it would be exciting to use this method to see if we could answer questions about climate change that happens on much shorter time scales – 100 years or less.”

Lasher and Yarrow focused on South Greenland because it’s at the crux of ocean currents and atmospheric patterns, two important natural phenomenons that could impact the ice sheet in the future, he said. This location is also close to Viking settlements.

But the work to recover the lake sediment cores, and the insects within them, wasn’t easy.

In order to even access the sites in Greenland, they needed permission from the local government and the support of the National Science Foundation. The US National Guard’s 109th Air Lift Wing in Schenectady, New York transported science cargo and the researchers to Greenland. Needless to say, it was a team effort.

The helicopter would drop off Lasher and his team at the site. Because they were in the middle of nowhere, they camped in tents and had to plan enough food to last up to four weeks. Lentils, macaroni and cheese, pesto pasta and chocolate bars were in heavy rotation, he said.

During the day, Lasher and his three fellow researchers would use inflatable boats on the Arctic lakes, covered in mud and battling mosquitoes.

“[We were] driving large tubes into the bottom of lakes to collect priceless archives of past climate change,” Lasher said. “It is hard work: I’ve been to Greenland for five summer field seasons, and would go back anytime. It is an amazing place.”

At night, the sun didn’t set until 10 p.m., and even then there was a glow on the horizon. The researchers were so exhausted that they learned to sleep through the perpetual light, Lasher said. Every few days, the tents and cargo were packed up into a giant net on the helicopter and moved to the next site.

Once they collected all of their cores and returned to the lab at Northwestern, they used radiocarbon dating on the material and analyzed it to get their data set. Their method isn’t like the one that other studies have used.

Recent research has shown that glaciers were close to Greenland when the Vikings lived there, so the researchers expected to find a climate record indicating those colder temperatures.

“So we developed a detailed temperature reconstruction from within the area of Viking settlement, and we found strong evidence for warmth during the settlement period,” Axford said. “Intriguingly, there’s also evidence in our record for extreme climate instability right before the Norse colonies collapsed, followed by a long period of cold climate until the 20th century. By no means can we say what happened to the Norse in Greenland. That question goes to the archaeologists. But now we can say that local climate changes apparently coincided with big events in their history.”

The climate was warmer by about 1.5 degrees Celsius. Axford and Lasher were also able to determine the cause of the climate change. And in another twist, it was not the North Atlantic Oscillation, the natural change in atmospheric pressure that causes climate anomalies in this area.

“We also conclude that ocean currents may have driven the complicated patterns of Medieval climate change around southern Greenland, namely which areas warmed and which areas cooled,” Axford said. “Warming in Medieval times was localized, unlike today’s global warming.”

He also warned that ocean currents in the North Atlantic are showing signs of changes today, which could have big impacts on regional climate and suggests the need to keep an idea on current changes in the oceans.

Going forward, the researchers want to create longer timescales of climate reconstruction to have a bigger picture of climate change. Their research could also determine more about glacier retreat in Greenland.

“We went in with a hypothesis that we wouldn’t see warmth in this time period, in which case we might have had to explain how the Norse were hearty, robust folk who settled in Greenland during a cold snap,” Lasher said. “Instead, we found evidence for warmth. Later, as their settlements died out, apparently there was climatic instability. Maybe they weren’t as resilient to climate change as Greenland’s indigenous people, but climate is just one of many things that might have played a role.”