Hari Budha Magar is laughing. He does that a lot. The ex-soldier turned mountaineer was being reminded that even at the top of the world in the freezing cold, there’s no danger of him getting frostbitten toes. Because he doesn’t have any.

Magar, a double above the knee amputee, is sitting in a southwest London charity office with his fundraising adviser hatching a plan to climb Mount Everest next spring. It won’t be the first time he’s tried to make the world-first ascent. As Magar puts it, he has climbed more than one Everest just to get to this point. But 2020 might finally be the year that he realizes his dream.

‘What about me climbing that mountain?’

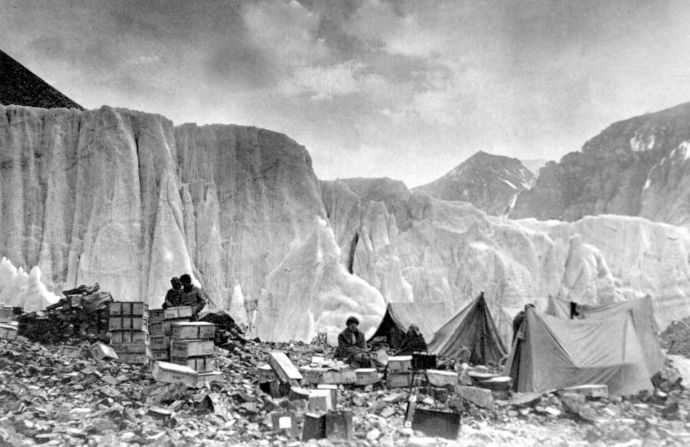

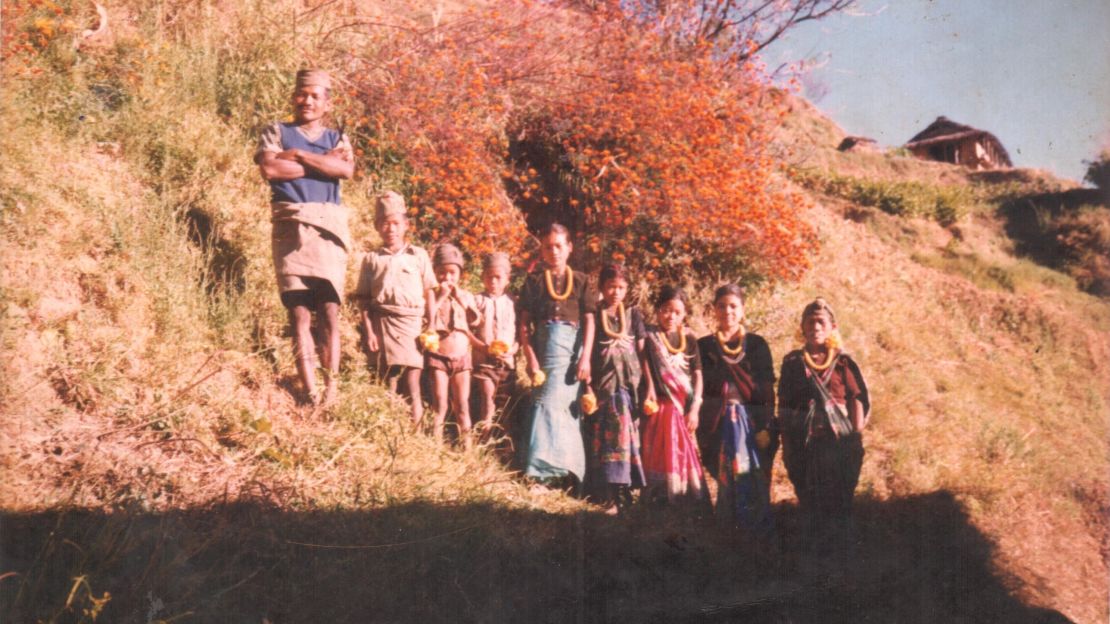

Magar grew up in a village in western Nepal, far from Everest. He would walk to school barefoot, and read about Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s first summit in 1953 in his textbooks.

“I used to think ‘What about me climbing that mountain?’” he recalls. Everest was for the privileged, however, and he was not.

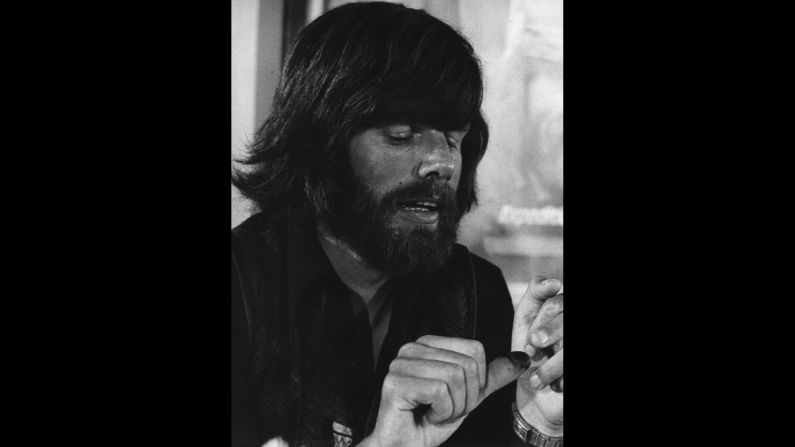

He joined the military aged 19 and passed the rigorous selection process for the elite Royal Gurkha Rifles, part of a brigade composed of Nepalese soldiers which has served in the British Army for over 200 years. Magar served across five continents in roles including sniper, covert surveillance and team medic. Then in 2010 an improvised explosive device detonated when he was on patrol in Afghanistan. “My life changed like that,” he says, snapping his fingers.

He was rescued by American soldiers and underwent two operations at Bagram Air Base before being flown to the UK for further treatment. Four years after sustaining his injuries, he was discharged from the military with the rank of corporal. He was 35.

“After my injury I just didn’t know where to start life,” he says. “To be honest I struggled, because I couldn’t go to the toilet myself, I couldn’t eat (by) myself or wash myself initially.”

Magar built himself back up “one step at a time,” regaining his independence. He took up sports – lots of them – as part of his rehabilitation. In 2011 on a ski trip in the German and Austrian Alps he turned to his instructors and broached the idea of climbing mountains. They said they would help.

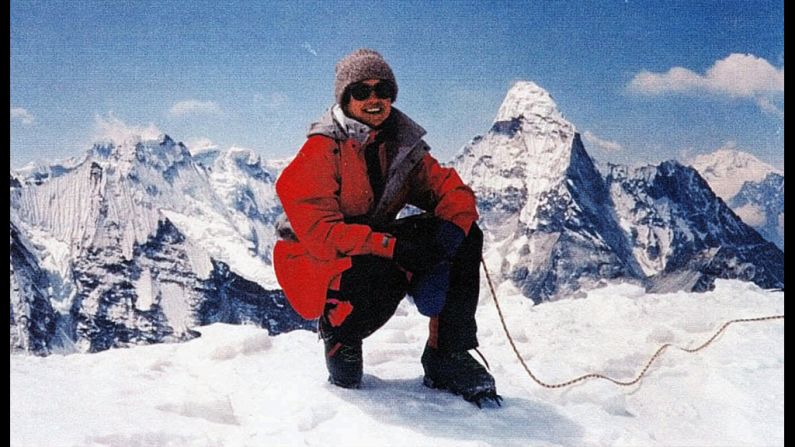

He traveled to Nepal with an able-bodied fellow Ghurka and montaineer, Krishna, and climbed to 4,700 meters. “Yeah, this is possible,” Magar thought, and the idea of Everest came into focus. Ahead of a summit attempt, Magar and a team climbed Mera Peak in Nepal in 2017, reaching 6,476 meters. But before he could take on Everest, in January 2018 the Nepalese government banned amputees and blind people from obtaining climbing permits, as part of new guidelines implemented in a bid to reduce accidents and climbing-related deaths.

The ban was appealed, and Nepal’s Supreme Court overturned the government’s decision in March 2018. Magar’s climbing window had passed however, meaning it was back to the drawing board for him and his team.

Now, nearly two years later, plans are ramping up once more.

‘It is better to die than be a coward’

Magar wouldn’t be the first double amputee to summit the world’s highest mountain – New Zealander Mark Inglis claimed that record in 2006. Double amputee Xia Boyu from China also scaled Everest in May 2018 (his fifth attempt) As Inglis and Xia are both below knee amputees, Magar would become the first double above knee amputee to attempt the climb.

“Above knee and below knee is a huge difference,” he explains. “Having a knee is so advantageous. You can lift your leg up and down. But (without a knee) you’re like a penguin.”

Today he’s wearing prostheses which replicate the length of a lower leg, with a foot and a hinge acting as a knee. But when he’s climbing he wears “stubbies,” a foreshortened prosthetic with plates at the base – plates that can be customized to feature crampons.

Inglis incurred frostbite and impact damage on his stumps during his climb, requiring surgery. He has been advising Magar on how to avoid injury, with possible technology including carbon fibre sockets with heating and insulation options. “Stump frostbite is a real challenge for Hari,” he explained via email. “I was in -50 (Celsius) knee-deep powder near the summit – that will equate to waist deep for Hari.”

“Every little thing helps above 8,000m,” Inglis adds, “the line between a good idea, a great idea, a bad idea and a life-saving idea is very fine.”

Even with innovations, there’s no getting around the sheer effort of the climb. In August Magar scaled Mont Blanc with amputee Justin Davis as part of his training. On summit day he toiled for 23 hours, he says, “crawling pretty much 90-95%.”

Magar says his movement is three times slower on his stubbies than an able-bodied person, meaning he and his group will spend a lot of time on Everest, requiring more supplies. “I’ve got a great team,” he says, and is under no illusion just how much he will rely on them.

His core team includes a Marine Corps Captain, Krishna and a Nepalese mountaineer with five Everest summits to his name. Plans are in place for eight high altitude Sherpas including a rescue team, six Sherpa porters and, pending confirmation, a physiotherapist, prosthetist and doctor.

An attempt on this scale comes with a hefty price tag: approximately $400,000 estimates Magar’s adviser John Simpson, founder and president of the On Course Foundation, a golf charity that provides career opportunities for wounded and sick military personnel and veterans. Simpson believes crowdfunding is the way forward and Magar has set a fundraising deadline of Christmas.

In the meantime, the former Gurkha says he just needs to keep on keeping on. “Train hard, fight easy” is the military mindset Magar says he is putting into action.

More ominously he also invokes the Gurkha motto, “It is better to die than be a coward.” As a father to three young children, it begs the question why he would take such a risk.

“Initially my wife said, ‘Stay at home and look after your children … they have gone through a lot,’” he says. “But this is what I want to do.” He’s clear-eyed about the dangers of the climb and says he is “completely prepared” should the worst happen.

“Lots of people say that I’m doing (this) for myself,” he says. “To be honest, this is my second life and I want to make my life as meaningful as possible before I die.”

“In Nepali we say that being disabled is ‘like a burden of the earth’ – that’s the mentality,” he explains. Magar hopes that with the summit attempt he can raise awareness of just what is possible for a disabled person in the country of his birth, and hopefully inspire others further afield.

“This is much bigger than just me,” he adds. “I think one person can make a huge impact in the world. I believe that.”

Correction: The story has been updated to correct the Gurkha motto.