Editor’s Note: Gene Seymour is a film critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post. Follow him on Twitter @GeneSeymour. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion at CNN.

Few people remember this, or don’t want to talk about it much. But before it became exalted as a mid-20th century miracle, as emblematic a triumph of collective human endeavor as the first lunar landing only a month before, Woodstock was being written off, while it was happening, as a disaster, a hippie Waterloo and the end of a beautiful dream of community.

Well, one out of three isn’t bad. Which one? We’ll get to that.

Fifty years ago this weekend, what was hyped as the “Aquarian Music Festival” with “3 Days of Peace, Love & Music” commenced on Max Yasgur’s 600-acre farm in Bethel (not Woodstock), New York. It would prove to be pretty much as advertised; indeed just a few months later the euphoric bubble would burst with the violence, including a stabbing death, of the infamous rock festival at California’s Altamont Speedway.

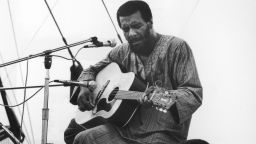

But for three days in upstate New York, there was none of that. Thirty-two musical acts spanning the rock ‘n’ roll zeitgeist performed at Woodstock, including Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Who, Sly & the Family Stone, the Grateful Dead, Santana, Janis Joplin, Joan Baez and Crosby, Stills & Nash.

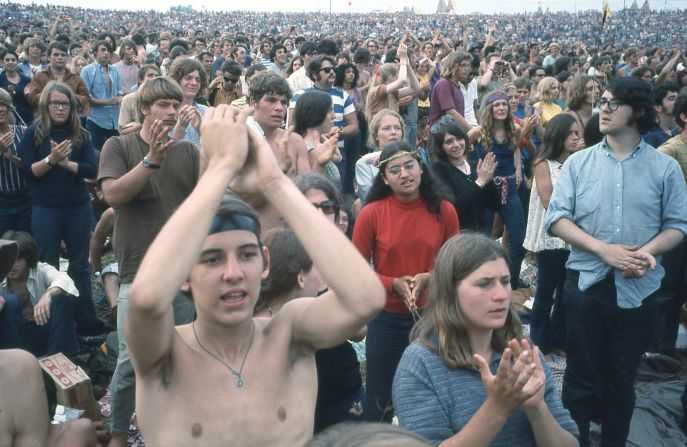

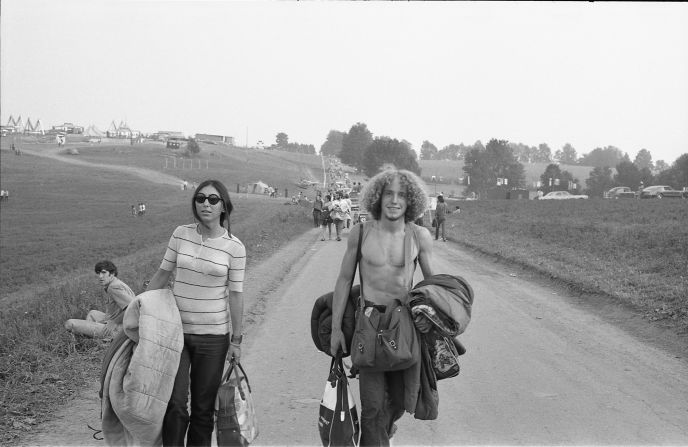

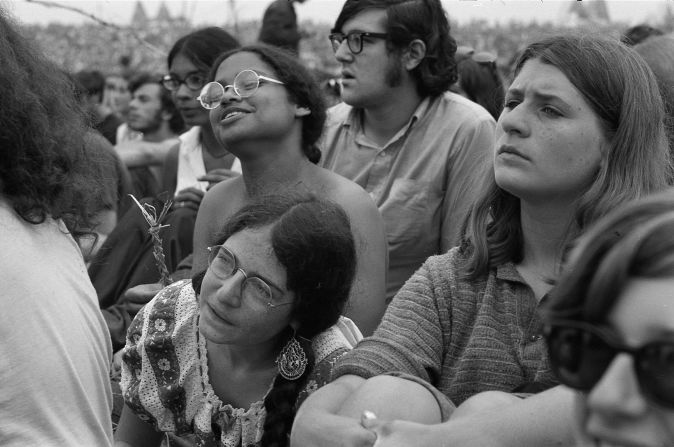

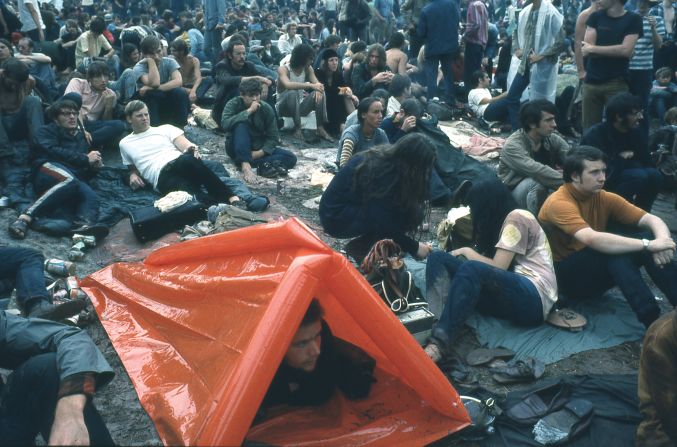

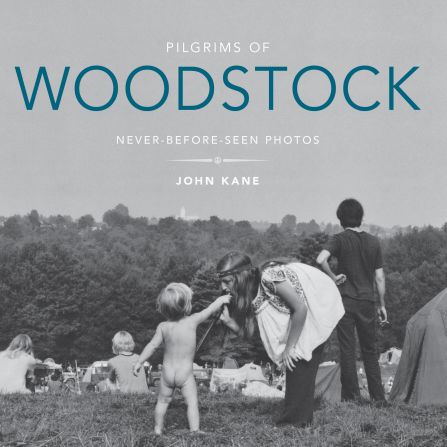

Never-before-seen images of Woodstock

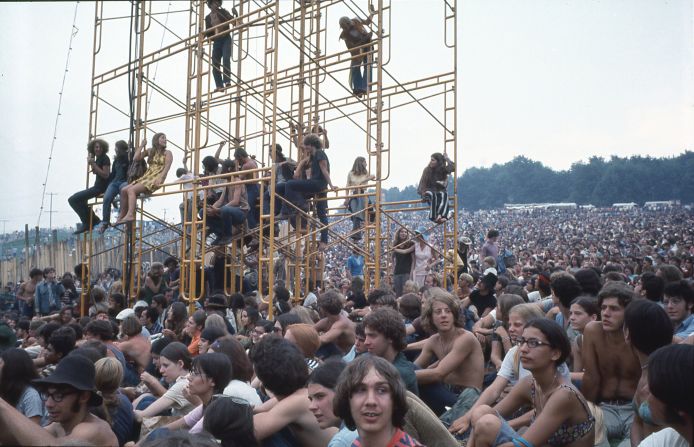

The latter trio admitted on stage to being quite nervous (the specific words Stephen Stills used were saltier than that) in making their first live appearance before a crowd that had by the third day morphed to almost, but not quite, the “half-a-million-strong” in the eponymous anthem that Joni Mitchell, a non-attendee, composed in its wake. (Estimates are closer to 400,000, but you know what, man? Who’s really counting at that point?)

Mitchell’s “Woodstock” and Michael Wadleigh’s similarly titled Oscar-winning documentary released the following year sealed the festival’s legend as a counterculture benchmark and an emphatic rebuke to those who were sure that the whole endeavor would, metaphorically speaking of course, go to pot.

CNN is marking the 50th anniversary with a special report airing this weekend (Saturday at 9 p.m. ET). And PBS’ “American Experience” has premiered another documentary, by Barak Goodman, titled “Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation.” Though Goodman’s film includes excerpts of performances captured by Wadleigh’s 1970 movie, it steps away from the stage to focus on what it took to put the “miracle” together.

Spoiler alert: It all didn’t just materialize out of the Catskills skies like a utopian vision, which is the way many, especially those who weren’t there, prefer to remember Woodstock. Even utopias take work. Somebody had to find the land, promote the event, figure out where to put the toilets, make sure there is enough food and medical care, and what happens if there’s a thunderstorm?

The process, along with a historical context of social and political upheaval fueled by the civil rights revolution and the Vietnam War, is detailed in Goodman’s account, which depicts the whole event as a sustained triumph of improvisation.

The festival’s founding quartet – Michael Lang, John P. Roberts, Artie Kornfeld and Joel Rosenman – didn’t always seem to know what they were doing. But along the way they learned how to set up on-site logistics (toilets included) and adapt to problems as they occurred. These mostly had to do with heavy traffic, and crowds so massively beyond what they expected that they had to make everything free and depend on the kindness of locals, who donated groceries when the food ran out.

The weekend’s other unsung hero was Hugh Romney, better known as Wavy Gravy, who led his “Hog Farm” commune members in providing not so much police protection as what Mister Gravy characterized as “please protection,” as in “please move along and help your neighbor out,” and so forth.

The film implies that the Hog Farm’s irreverent equanimity towards others helped facilitate the no-sweat communion among festival goers in helping each other, whether in dispensing food or aiding medical staff in bringing down those on bad acid trips. This happened in what were designated as “freak out tents.”

As somebody at the start of the PBS film says, “It could have been a disaster.” And the newspapers that weekend (and I know this because I was working on one at the time) believed that it was, based on scattered reports from the site. Then-New York governor Nelson Rockefeller believed those stories enough to consider sending in troops to shut it down, but was instead convinced that all that was really needed from the military were airlifted medical supplies.

In the end, the vision of Woodstock that prevailed in history was one that Yasgur himself defined as a benediction to the grateful, gleeful throng during the festival: “You’ve proven to the world that a half-a-million kids can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but three days of fun and music.”

Is it any wonder that people have tried in the decades since to duplicate this miracle? And is it any wonder that they never have? It shouldn’t be.

Less than five months after the three-day utopian community left Bethel behind, the yang to Woodstock’s yin ensued at a rock festival at Altamont, where a Rolling Stones performance was marred by the murder of an African American man in the audience along with three accidental deaths (the same number, ironically, at Woodstock), several injuries, stolen cars and vandalized property.

In other words, the harmonic convergence of peace and community Woodstock seemed to bring into being had dissipated almost as quickly as it materialized. What seems apparent 50 years on is that Woodstock was exactly what it appeared to be: a series of accidents that somehow coalesced into something that may never be duplicated.

It’s possible, though not inevitable, that we may find something other than music to bring people together in a similar way – though that may require us to look away from the handheld screens that let us stare into the past and present, but block us from seeing each other as Wavy Gravy and many others tried all those years ago.