Story highlights

The Voynich manuscript has been dated to the middle ages

It is written in incomprehensible text and has spawned countless theories as to its meaning and origins

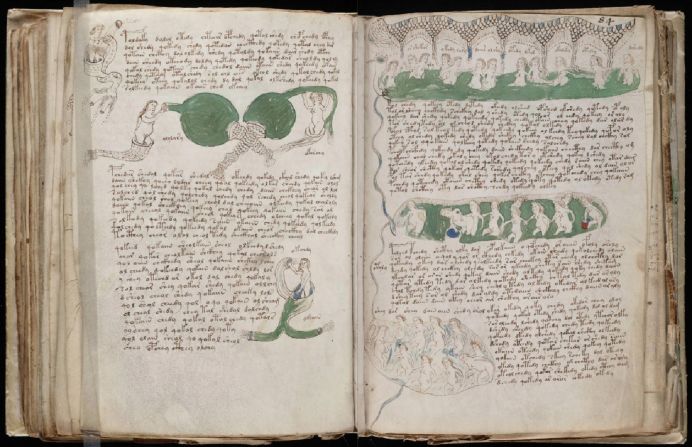

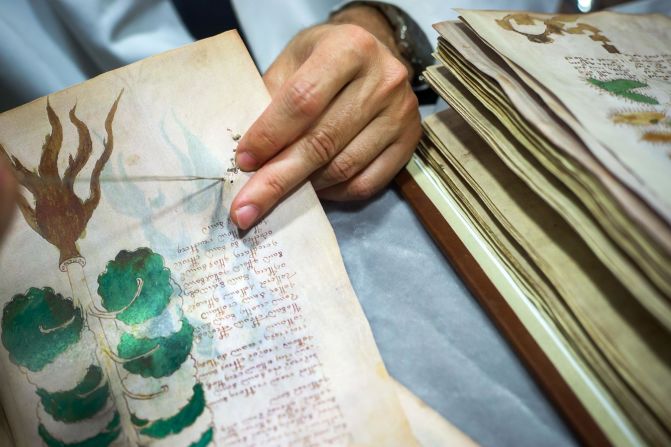

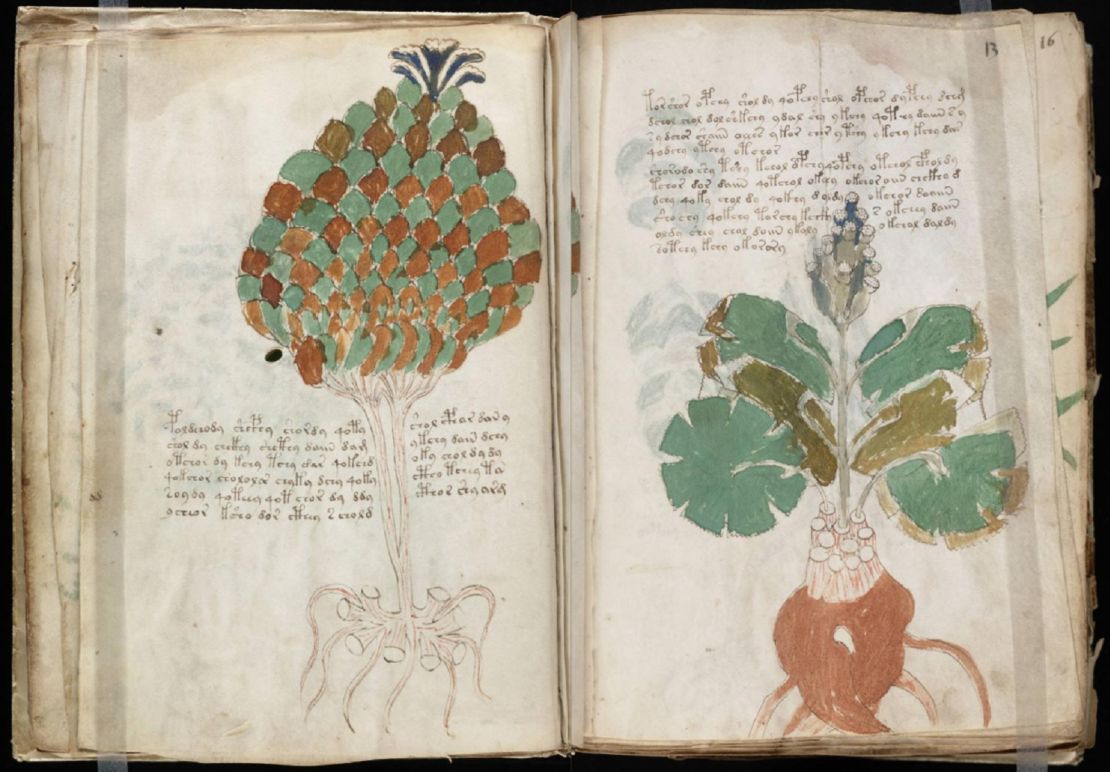

Naked women in pools of green liquid, strange looking plants, and text written in an unknown alphabet; they can all be found on the delicate parchment pages of a mysterious manuscript from the 15th century. And nobody knows what any of it means.

Frayed, browned and in fragile condition, the Voynich manuscript currently resides deep in a basement at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library but digitized copies of it are available for free online.

Since it came to light over 100 years ago, many have tried and failed to decode the text – from US Army cryptographers to ordinary citizens postulating theories in the deepest corners of Reddit.

Its author and original title are unknown, and it is named for the collector and bookseller Wilfrid Voynich, who purchased it in 1912.

Ever since Voynich showed it off to the world, the incomprehensible text and cryptic illustrations have spurred countless theories about its meaning, origin, and the identity of its author. Some thought it might have been written by Leonardo Da Vinci or maybe even an autistic monk, others felt it might simply be an elaborate prank.

Read: Medieval grave reveals rare ‘coffin birth’ and neurosurgery

So what do we really know about the Voynich manuscript? Why has it captivated the imagination of so many through the decades? And will its mysteries ever be solved?

‘People have lost their families over it’

Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America and a longtime Voynich scholar, says the first recorded appearance of the manuscript was when it was bought in the late 16th century by Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II, who believed it had been written by 13th century British philosopher and alchemist Roger Bacon.

It then apparently traveled around Europe, disappearing for 250 years, before eventually being acquired by Voynich. Although Voynich never revealed where he got the manuscript, Davis says that his wife disclosed after his death that he had bought it from Jesuits outside of Rome.

Read: Oldest ‘tattoo art’ discovered on Ancient Egyptian mummies

In 2011, carbon-dating revealed the parchment dates back to the early 15th century, somewhere between 1404 to 1438. Analysis of the ink confirmed it was consistent with what was used during that period.

That dating rules out some of the names postulated as being the author, like Bacon, Da Vinci and Voynich himself. But beyond those facts, the manuscript offers more questions than answers.

It’s that sense of mystery that has captured the public imagination, and compelled so many to attempt to decipher its meaning.

“There are a lot of different approaches that people have taken over the years and a lot of people have given up,” said Davis. “And some people have lost their fortunes and families over this manuscript because of their obsession with it. There are people who claim every once in a while to have decoded one word, but nothing else.”

While the media regularly reports that someone has finally cracked the code, none of the claims have so far stood up to close scrutiny.

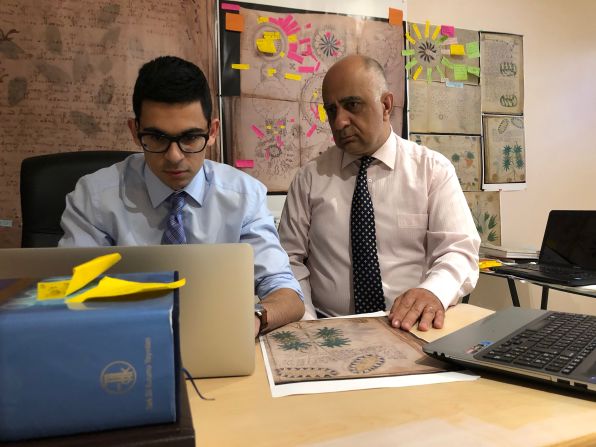

One recent theory that triggered an entire news cycle was the claim by a professor and grad student at the University of Alberta in Canada that artificial intelligence had finally cracked the code.

Read: The ancient Greek masterpiece etched on a tiny gemstone

They claimed the text was originally written in Hebrew, before being encoded, but Davis and others have disputed that idea.

Davis said that ultimately, in order for a theory to hold up, it must be vetted, be repeatable by other scholars, and result in something that makes sense.

Countless theories, no solution

Many will want to apply those criteria to a new theory, from a family in Canada, who claim to have deciphered the text.

Ahmet Ardic – an electrical engineer by profession, whose lifelong passion has been researching Turkic languages, linguistics and etymological roots – stumbled upon a copy of the Voynich manuscript online four years ago.

Like so many others, he was intrigued and began working on it by himself for a year. He then enlisted his two sons, Ozan and Alp Erkan, to help.

The Ardic family have published a video on YouTube explaining their theory. They say they’re certain the manuscript is written in a type of Old Turkic dialect or a combination of dialects – mostly written in phonemic orthography, or language written as it is spoken.

Ozan said his family have figured out at least 300 words and is confident there is now sufficient vocabulary to read at least 30% of the manuscript.

They say the manuscript contains recipes, details of ointments and even entries on abortion, how to conduct a proper C-section procedure, and disparaging common misconceptions of the time, such as eating more in order to bear a male child.

Read: 1,200-year-old comb holds clues to Viking runes

This summer they plan on submitting their research to the academic journal Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Culture.

“At this point we’re not exactly pushing a theory as much as proving a fact,” Ozan, 20, told CNN. “We analyzed this and we wouldn’t be presenting this if this wasn’t Turkish.”

Intriguing claims

Davis says their claims hold up pretty well so far, although she is eager to hear from an Old Turkic scholar who can vet the family’s work.

“I don’t know the first thing about old Turkish but it’s very intriguing,” she said. “It certainly fits the known history of the manuscript, it suits the contents. When you put the whole thing together, the contents suggest that the manuscript was produced for medicinal purposes.”

Whether or not their theory withstands expert analysis, it’s unlikely to end our obsession with the document.

“I would say the Voynich manuscript stands at the intersection of the middle ages – which is a topic that is really fascinating to the general public – and the unsolvable mystery,” Davis said.

“It’s had an incredible journey and right now, in this very moment, it’s sitting in a safe in a sub-basement at the Beinecke Library, in the dark, patiently waiting for someone to decipher and uncover its secrets.

“It’s magical. It really is. There’s nothing like it.”