Story highlights

Constitutional change expected to give Communist Party sweeping new anti-corruption powers

Paramilitary police placed under direct party control this week

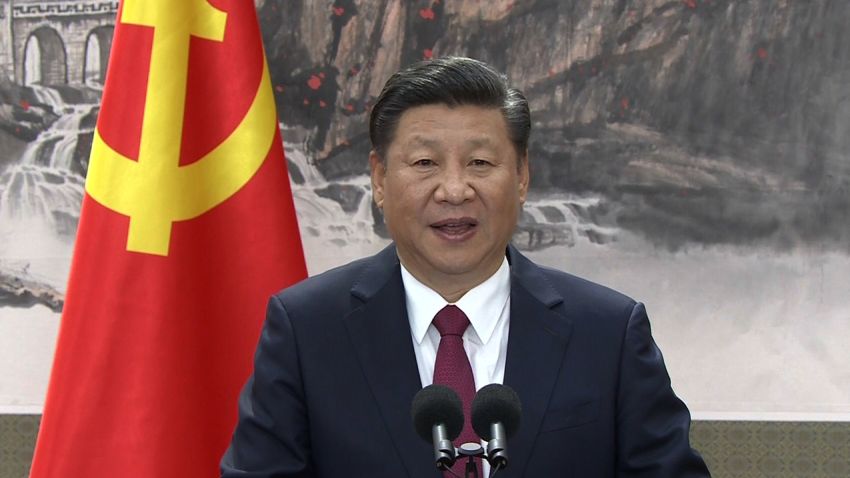

Chinese President Xi Jinping had a good 2017, but 2018 may be looking even better.

The ruling Communist Party (CCP) will discuss changing the country’s constitution for the first time since 2004 next month, with analysts predicting Xi will further cement his grip on power.

The change could clear the way for the creation of a National Supervision Commission (NSC), a country-wide anti-corruption task force with sweeping new powers, though some have speculated there could also be a move to abolish term-limits on the Presidency, allowing Xi to serve on past 2022.

This comes on the back of a move by Xi this week to shore up his command of the country’s armed forces by moving control of paramilitary police from the government to the CCP.

Absolute power

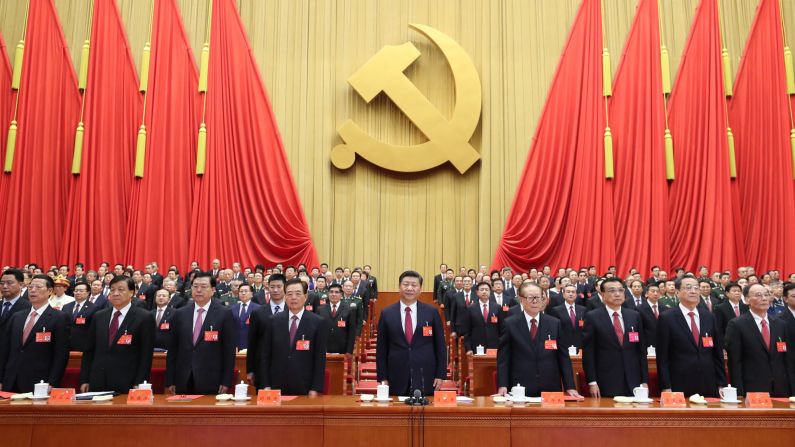

In October, the CCP enshrined “Xi Jinping Thought” as a guiding principle, elevating him to a level no Chinese leader has held since Mao Zedong.

At the same time, Xi unveiled a new leadership team which did not include any obvious successor, increasing speculation he may hold on to power at the end of his second five-year term as President.

Margaret Lewis, an expert in China’s legal system at National Taiwan University, said Xi had already scored a “major political victory” with the addition of his “Thought” to the party constitution, and “does not need to change the rules on term limits to remain extremely powerful.”

Unlike the presidency, there is no restriction on how long Xi could serve as CCP General Secretary, the position from which his true power flows, though traditionally both titles have been held by the same person.

Deng Xiaoping, during his time as leader, gave up most official positions but retained a huge amount of control over decision making, Lewis said.

“Titles matter, but there is more to power in China,” she said, particularly the “extent to which other top leaders act as a check on his power.”

This week, the Politburo, the party’s top body, underwent a Mao-era style self criticism session in which they vowed to follow Xi’s lead, according to state news agency Xinhua.

“Xi has shown firm faith and will, clear commitment to the people, extraordinary political wisdom and tactics and a strong sense of responsibility, in leading the CPC and China in the great struggle with many new contemporary features,” the Politburo said in a statement following the “meeting of self reflection.”

William Nee, a China researcher for Amnesty International, said self criticism meetings “are a very old tool … to get people to admit their faults publicly, talk about the problems in their work styles and to profess loyalty to the party center and in this case explicitly to Xi Jinping.”

Lewis said the session was typical of how under Xi “there is little tolerance … for the slightest wobbling off the party line.”

Constitutional changes

Creation of the National Supervision Commission would expand that discipline and control to a broad swath of society, analysts said.

Tackling corruption has been a major priority for Xi, but it has previously been focused on party bodies and the military, attracting considerable public support even as some critics accused him of using the campaign to go after potential rivals and shore up his power base.

In a recent report analyzing the proposed NSC framework, Amnesty warned it would “legalize a form of arbitrary detention and create a new extra-judicial system with far-reaching powers that has significant potential to infringe human rights.”

Most significantly, the NSC would replace the much-criticized shuanggui system – in which party members under investigation were held in secret prisons and subjected to abuse and torture – with a new “retention and custody,” or liuzhi, system.

That system would apply not only to party members, but also to people working in state-owned companies, scientific research, education, healthcare and other public bodies, in what Nee described as a “very worrying” development.

The NSC is one of several new laws which “give the party and the government sweeping powers,” he said.

While much of these changes involve legalizing activities which already go on unofficially, Nee said this may be motivated by a desire to gain international legitimacy for and cooperation with China’s anti-corruption drive.

Under “Operation Foxhunt,” Beijing has requested many foreign governments to extradite people accused of corruption and issued Interpol notices for alleged economic criminals, with limited success.

“One sticking point for a lot of countries in repatriating allegedly corrupt officials is the (existing system) is technically an extra-legal body,” Nee said.

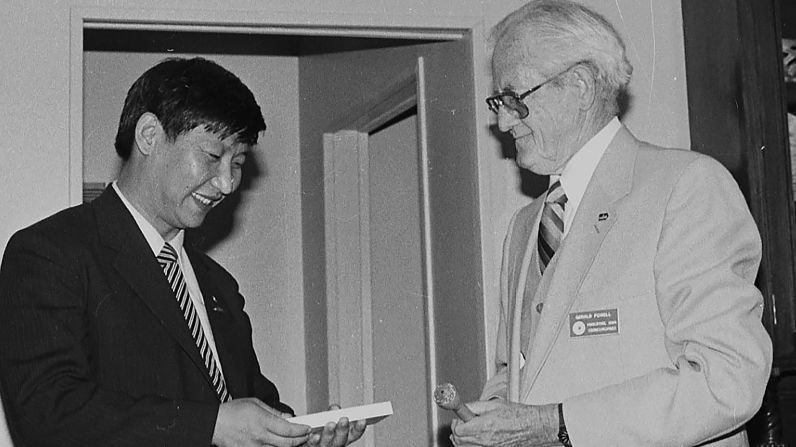

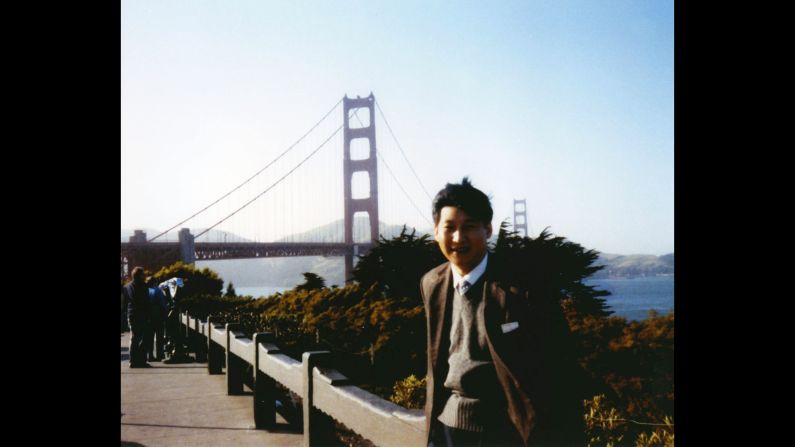

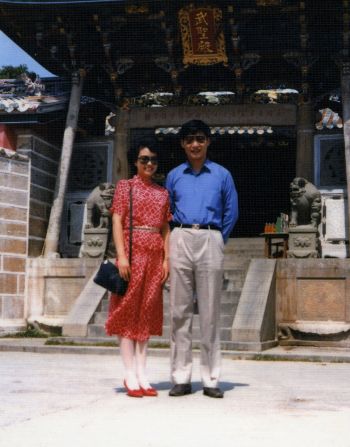

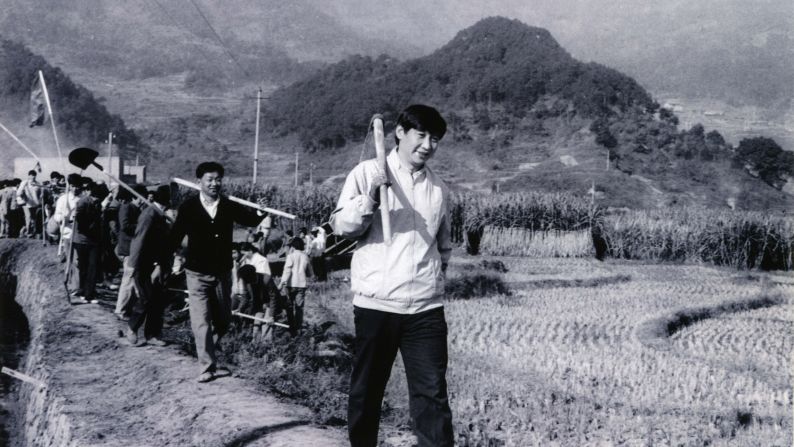

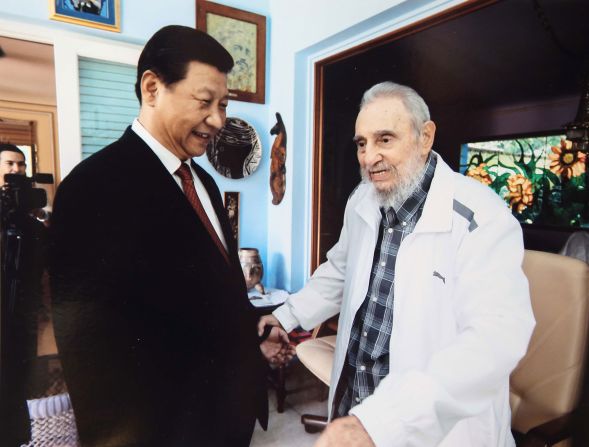

Chinese President Xi Jinping

Military might

As well as shoring up his power over the party, Xi’s tenure has seen a major reform of the country’s armed forces, bringing them thoroughly under his personal control.

“The importance of the Party’s control over the military is an oft-repeated phrase, but Xi has emphasized it heavily during his tenure,” Tom Rafferty, China manager at the Economist Intelligence Unit, told CNN earlier this year.

That continued this week, with command of paramilitary police forces placed under the party’s Central Committee and the Central Military Commission, both of which are headed by Xi.

The People’s Armed Police (PAP) are often deployed to tackle riots, large-scale protests and terrorist attacks, and are “very involved in the maintaining of social order,” Nee said, particularly in Tibet and Xinjiang, both of which have large non-ethnic Chinese populations and history of protests and unrest.

Previously the PAP answered in part to the State Council, a governmental body that is nominally separate from the party system. Xi ally Wang Ning, an army general who had no police experience prior to taking the job, has helmed the PAP since 2015.

In an editorial Wednesday, the People’s Daily, the mouthpiece of the party, said the move was “a significant political decision … that will strengthen the party’s absolute command over the (People’s Liberation Army) and other branches of the people’s armed forces and will ensure the stability and prosperity of the party and the nation.”

Hong Kong-based China analyst Johnny Lau Yui-siu told the South China Morning Post the move was designed to “put all China’s military power in Xi’s hands.”