Born in Morocco and still a devout Muslim, Ahmed Aboutaleb is – it would seem – precisely the type of person that far-right leader Geert Wilders wants to kick out.

Aboutaleb, the mayor of Rotterdam, is sanguine about his country’s upcoming election. Perhaps it is because he knows Dutch identity better than most.

“The identity of the Netherlands. It will not be about the economy; it will not be about jobs,” he said.

But there’s a curious thing about Abouteleb: He’s one of the most popular politicians in the country, even, he says, among many Wilders supporters.

Rotterdam, and three people in it, are a microcosm of the March 15 parliamentary election.

MORE: Dutch journalist breaks down the Dutch election

Wilders’ precursor

Geert Wilders is a bit of an enigma to those who have traveled to the Netherlands.

How can a country so famous for its liberal politics, which allows prostitution, soft drugs, and gay marriage, also propel Wilders to the fore?

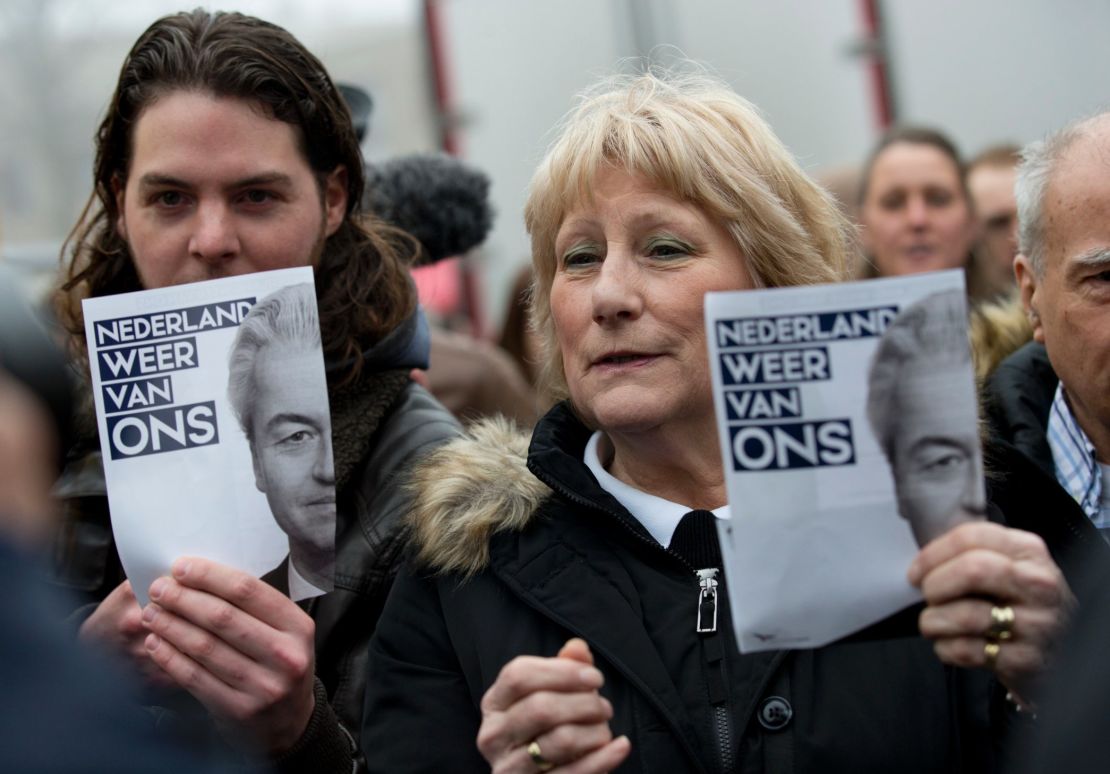

He wants to close all mosques in the country, ban the Quran, “preventatively” lock up radical Muslims, and stop all immigration from Muslim countries. Nonetheless, his Freedom Party is – for the first time – poised to become the largest in the country.

Perhaps more than any other right-wing movement, Wilders does not spend a lot of time talking about the economy – he is almost singularly focused on Islam, and Dutch identity.

“Look at the Islamization of our country,” Wilders said recently in Spijkenisse, just outside Rotterdam. “The Moroccan scum in Holland – and once again, not all are scum, but there is a lot of Moroccan scum in Holland – who make the streets unsafe.”

That caveat echoes Donald Trump’s campaign-launching proclamation that Mexicans bring drugs and crime, and are rapists, though “some” are good people. Wilders has made his affection for President Trump no secret – and attended the Republican Convention in July.

Wilders’ rhetoric brings scorn from the Dutch establishment, but is an incontrovertible truth to Ronald Sørensen. “I saw that there was no integration whatsoever,” he said on a frigid February day near Rotterdam’s city hall.

In late middle age, Sørensen has maintained the look of a schoolteacher – which he was for decades, before entering politics – perhaps with a dash of sea captain, in the form of a scruffy white beard.

For decades, he taught in the city he had always called home. He grew increasingly frustrated with what he saw as a lack of integration on the part of Moroccan and Turkish students of his. He also believes the ruling “elite” was willfully ignorant of the problem. Just less than 20% of the city’s population is now Muslim.

“I spoke about it with my colleagues,” he said. “And they said, ‘Eh, just leave it. It’s always been like that.’ But I am not someone who can just leave it.”

He founded a new party, Livable Rotterdam, and soon brought on board the man with the charisma: Pim Fortuyn.

We walk from Rotterdam’s ornate city hall through a soulless modern shopping plaza to a statue of Fortuyn.

At first blush, Fortuyn was an odd choice for a far-right party – flamboyantly gay and dapper, he often posed with his two small spaniels.

But he was also uniquely Dutch. Fortuyn was intolerant of intolerance; he saw conservative Islam as a personal and existential threat.

“There were people on the street who said to me, ‘If he’s a fascist, then call me a fascist too,’” Sørensen said. “Now in the Netherlands, that’s a terrible thing. But people saw that everywhere lies were being told about him.”

A portrait of Fortuyn, spaniels and all, still hangs above a doorway in the Liveable Rotterdam office he once occupied.

Before he could reach the highest levels of the Dutch government, Fortuyn was assassinated by a man who said the far-right leader was scapegoating Muslims. But it is undoubtedly Fortuyn’s ideology, which was born in his city of Rotterdam, and in the ideology of Livable Rotterdam, that lives on in Wilders.

“It’s very clear,” Sørensen said. “I, of course, as a history teacher, read the Quran and parts of the Hadith. And then I say no – that’s not only counter to Dutch values, it’s also against European, Western values.”

“We are for equality of men and women. We are for sexual equality. We are for religious equality – minorities can also profess their religion. And if you then read the Quran and read the statements of their Prophet Mohammed, then that’s not something that you can put together.”

The imam

“Islam is a European religion,” said Imam Azzedine Karrat, sitting in djellaba and skullcap on the top-floor library of the Essalam mosque. At the edge of the room, a teenager quietly works at a pod of computers.

It “is a European religion, and therefore also a Dutch religion. It is part of this society … “It is there. We have to deal with it.”

Karrat, born in Morocco, came to the Netherlands as a teenager. Not yet 30, he now leads the country’s largest mosque. It’s an imposing structure on the city’s largely immigrant south side, set just off the New Maas river and a stone’s throw from Feyenoord stadium, home to one of the country’s most important football teams.

A debate about whether integration works, he said, is no longer “of our time.”

“I try to be a practicing Muslim, but I’ve never had a problem with the Dutch norms or values or with the Dutch law.”

“Islamization,” he said, is used “with one goal, and that is only to spread angst.”

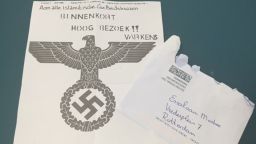

His mosque has received threats, including a swastika-decorated letter warning of the delivery of “pigs” in the near future.

The letter appears, so far at least, to be a relative anomaly. Karrat remains steadfast in his message of love and acceptance.

The call to prayer on that Thursday afternoon brought in a decidedly older crowd – men in their 50s and 60s who were perhaps among the first-generation migrants encouraged to move to the Netherlands decades ago.

Now it is – above all – the young people that the imam must reach if he wants to spread his message of Dutch and Islamic values coming together as one.

Wilders, he said, is “using Islam to strengthen his position.”

“If you look at the reality, at the society, then I don’t always see that. I see tolerance, I see respect, I see acceptance.”

But fear remains.

“After the attack on the mosque in Canada, I found myself thinking during prayer, ‘What if someone came in now?’”

The truth teller

Mayor Aboutaleb had his own moment of worldwide acclaim – an interview with Dutch news in the aftermath of attacks in Paris on the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo.

“If you don’t see yourself here because you don’t like seeing humorists that make a newspaper then yeah, can I say it like this – get lost!”

The interview was trumpeted by conservative media, especially in the United States, who held him up as a Muslim telling the truth about his own religion. (Perhaps it helped that some translated his comments as “F*** off.”)

That reputation as “truth teller” has undoubtedly helped at home, too.

When “you migrate, it’s your free choice,” he said sitting in a cafe in Rotterdam’s massive covered market. “So it’s up to you to make the choice to be part of that society.”

“But in the end, if after a couple of years you discover that the values are not your values … [then] it’s also your choice to say, ‘I don’t want to stay here.’”

They sound like the right words to co-opt Wilders’ more radical messaging, but Aboutaleb – a member of the Labor Party – is sitting out the national election.

Dutch politics, always fractured, are particularly so this year. Dozens of parties are competing. If, as they promise, they are to shut Wilders out of government, it will mean the formation of a messy multi-party coalition. The mayor’s line, unsurprisingly, is that he has “the best job ever.”

Dutch mayors are appointed, not elected.

Clearly, though, he understands that it’s a difficult time for a European liberal like him.

“There is a kind of a mixed feeling among citizens,” he said.

“The fact that there are a lot of immigrants, and a lot of immigrants are still coming – the refugee crisis from the Middle East – and they are concerned about their own future.”

“They lose their jobs. The people from Eastern Europe are coming in, taking the jobs. And it’s more or less the same agenda as in the United States when it comes to migration and the fear among some group of people who are the losers in the social stratification of the country.”

But he’s not afraid of Wilders.

“The best cleaning machine we know of in our system is democracy.”

Walking around the market, the mayor is a star – posing for pictures and shaking hands. He gives CNN’s Atika Shubert a Dutch classic – raw herring and onions, eaten by hand, held by the tail. (He demurs.)

“People finally judge a function of government when it comes to their own things – their house, their car, the school, the kids, and the quality of the public life in their own surroundings. So we have to come down from the meta politics to really the daily practice of citizens.”