Editor’s Note: Nick Gilbert is a writer & expert specializing in fragrance.

Story highlights

New technologies are changing the way scent is captured and perfumes are made

Perfumery has always been an intricate science; much more effort goes into capturing a scent than those outside the industry might imagine.

Over the last two decades, chemists have used innovative new technology to add an even larger array of scents to the perfumer’s palette, enabling them to create fragrances that have never been smelled before.

For thousands of years, scents came directly from nature. Resins were collected from trees and burned as offerings to the gods; aromatic flowers and herbs were steeped in oils to release their fragrance before being blended and worn.

After steam distillation – the process of boiling petals and leaves and cooling the evaporated oil – was perfected in the 11th century, little changed about the way perfumes were made until the industrial revolution of the Victorian age.

Then chemists began isolating and synthesizing the aromatic chemical compounds present in nature that perfumers loved, such as vanillin, the smell of vanilla.

These “isolates” allowed perfumers to break from what was strictly found in nature and create entirely new scents.

“Many enduring perfumes (from the last century) contain an overdose of a newly available raw material,” independent French perfumer Stéphanie Bakouche said.

“Perfumers like Ernest Beaux, who created Chanel No. 5, famed for its unprecedented dose of aldehydes, and Edmond Roudnitska, who enlivened Eau Sauvage with a dose of hedione, were pioneers.”

Scent reimagined

In the 1980s, fragrance house International Flavors & Fragrances (IFF) invented a new way to capture the volatile molecules of virtually any scented object. Dubbed Headspace technology, it completely changed the industry.

Headspace acts like a camera that takes a snapshot of the components of a scent – whether sublime or obscure – and allows them to be recreated in a laboratory.

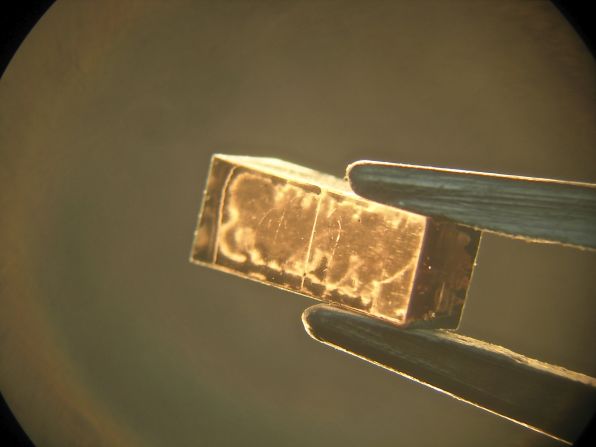

These diamonds were grown in a lab

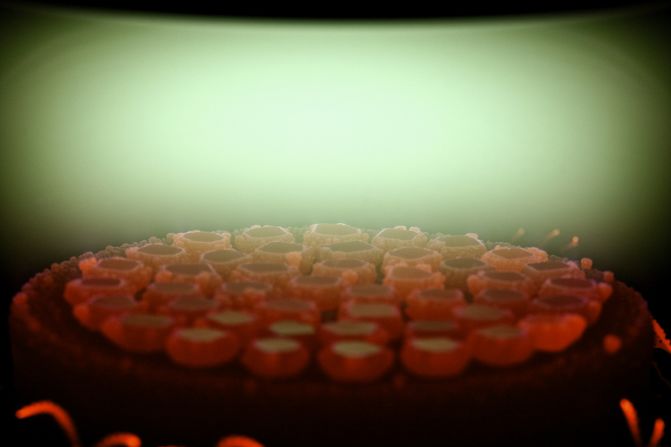

From the smell of a temple (incense, leather and warm stone) to the aroma at the top of a skyscraper (ozone, glass, metal and concrete), even a rose in zero gravity aboard a space shuttle (fresher, sweeter and more metallic), Headspace has captured them all.

Shiseido used the ‘space rose’ analysis – apparently an entirely unique smell – to create its perfume called Zen.

Headspace technology has also helped make Frederic Malle’s floral fragrances among the most beautiful and realistic on the market. One of his most popular fragrances, Carnal Flower, is made using three different Headspace analyses, he said. “The scent of the tuberose flower changes during a 24-hour period,” Malle, founder of Editions de Parfums, explained. “It is common sense.”

Nature made complete

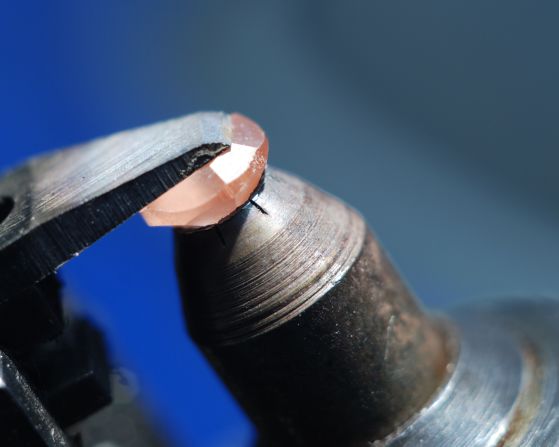

IFF’s Laboratoire Monique Remy developed another innovative process while working on the Rose Essential scent.

Just as boiling vegetables for too long can result in lost nutrients, distillation loses some of the best parts of a smell to the water and can often damage the resulting oil.

The three-step process behind Rose Essential aims to prevent this and combines hydro-distillation with steam stripping – capturing scent molecules from the remaining water – to offer a more complete, realistic, and fresh extract compared to traditional rose essences.

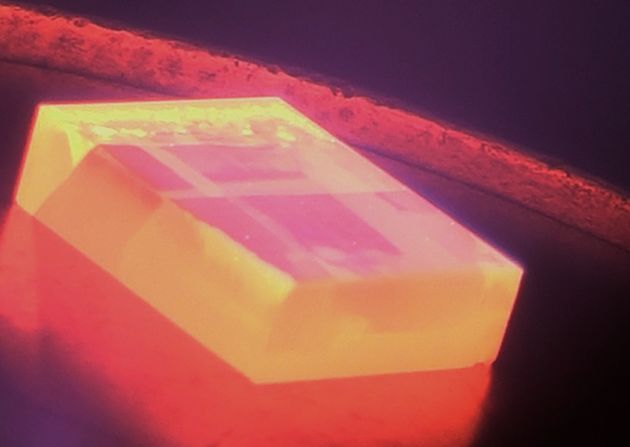

CO2 extraction also aims to capture as much of the scent as possible from a natural material. This technology uses carbon dioxide, which turns to a liquid at high pressure, and passes it over the natural material to extract all the scent components without damaging them.

“CO2 extracts express nature like no other extract,” says Bakouche. “They offer some facets that don’t exist in essential oils or absolutes – where the molecules are damaged or burned away.”

The high cost of these raw materials limits their use in fragrances so as not to drive up the cost to consumers – but to perfumers, the aroma is worth the cost.

“Blackcurrant CO2 is popping up everywhere, from niche fragrances like Miller Harris’ Rose Silence, to Armani’s blockbuster Si,” adds Bakouche. “And the iris is breathtakingly beautiful.”

Genetic facsimiles

Some of the most exciting new scent materials are a result of biotechnology.

Scientists can now genetically alter yeasts, so that instead of fermenting sugar into alcohol, they produce fragrant compounds that replicate natural and artificial flavors and smells.

Clearwood, an award-winning compound created by scientists at fragrance house Firmenich, for example, can be used as a replacement for patchouli due to its similar chemical composition.

Vital to perfumers, patchouli is used to scent everything from laundry powders to exclusive perfumes, but a combination of crop shortages and deforestation has restricted supply and caused the price of the oil to skyrocket.

Although Clearwood misses some of the forest floor character of the natural oil, it can be used as a sustainable replacement for patchouli that prevents the cost of the natural oil shortage from being passed on to consumers.

Future of fragrance

How will future fragrances be composed?

The next innovation might not be in capturing scent, but rather in delivering it.

Olfa Labs in London, for example, are attempting to develop technology that digitally creates odors from ambient molecules in the air.

“We first have to prove it is possible to faithfully replicate a small palette of essentials and absolutes,” says cofounder Oscar Spear. “For the perfumer, it would mean composing fragrances on a digital organ, with digital molecules.”

It might sound a little bit like the food replicators from Star Trek – but it would hardly be perfume’s first technological revolution.