Watch: What's pulling America apart?

Christine Barabasz, a Texas resident, has been happily married for 50 years — and for most of that time, she and her husband have been politically in sync.

But then 2016 happened. She supported Hillary Clinton; her husband voted for Donald Trump.

One of the reasons she thinks she and her husband have diverged politically: their different media consumption habits. She prefers watching NBC, while he now listens to Rush Limbaugh and reads The Drudge Report. The consequence, she writes, is that they “are completely unable to discuss anything political together.”

Christine is one of our many readers who told us that the rise of right-wing media was to blame for the state of political division today. But many conservatives believe the mainstream media has left them out — or left them behind — creating a void for partisan outlets to fill.

That’s a key part of the road to today’s “Fractured States of America.” But it’s more complicated than that. Americans have sorted themselves into predominantly liberal and conservative enclaves. Social media has accentuated partisan division and enabled extremists to get their views out. And the political system has abetted the fracture by drawing voting district lines in ways that encourage members of Congress to resist compromise.

We see the results in today’s impeachment debates, but as CNN senior political analyst John Avlon points out, division existed before Donald Trump’s presidency — and, according to Pew Research Center, almost two-thirds of Americans think it will continue long after.

Blame it on our psychology

While there are many factors playing into today’s division, the simplest one may be human psychology. Research suggests that often we do not draw conclusions based on a thorough examination of the facts. Rather, we reach a conclusion based on our prior beliefs — and then selectively bring evidence to support it.

As scholar Martin Bisgaard explains, “In terms of politics, this means that partisans want to confirm their existing beliefs on political issues and favor politicians who represent those beliefs.” And what better example than the impeachment inquiry into Trump.

For most Democrats, the log of Trump’s phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, text messages between senior US diplomats and public depositions before the House Intelligence Committee confirm what they already believe to be true — that Trump poses a threat to the American people and puts his own interests before everyone and everything else.

For many Republicans, the phone log, text messages and public depositions prove just the opposite — that the President was simply asking a foreign ally to assist in an investigation into potential corruption by a leading Democratic presidential candidate.

And while impeachment polls have varied in the last few weeks, one thing remains clear: large majorities of Democrats continue to support impeachment (and removal), and large majorities of Republicans continue to oppose it. Both groups likely made up their minds long before the inquiry began — and are using the evidence they have collected to confirm their preexisting partisan views.

Won’t you be my neighbor

But it’s not just about psychology; it’s also about choice. When journalist Bill Bishop left his ultra-blue hippie enclave of Austin, Texas, he did it because he wanted to live where the polka action was — La Grange, Texas.

It came at a personal price. Sixty-five miles southeast, he crossed into another political world, one in which Trump was beloved and Clinton scorned.

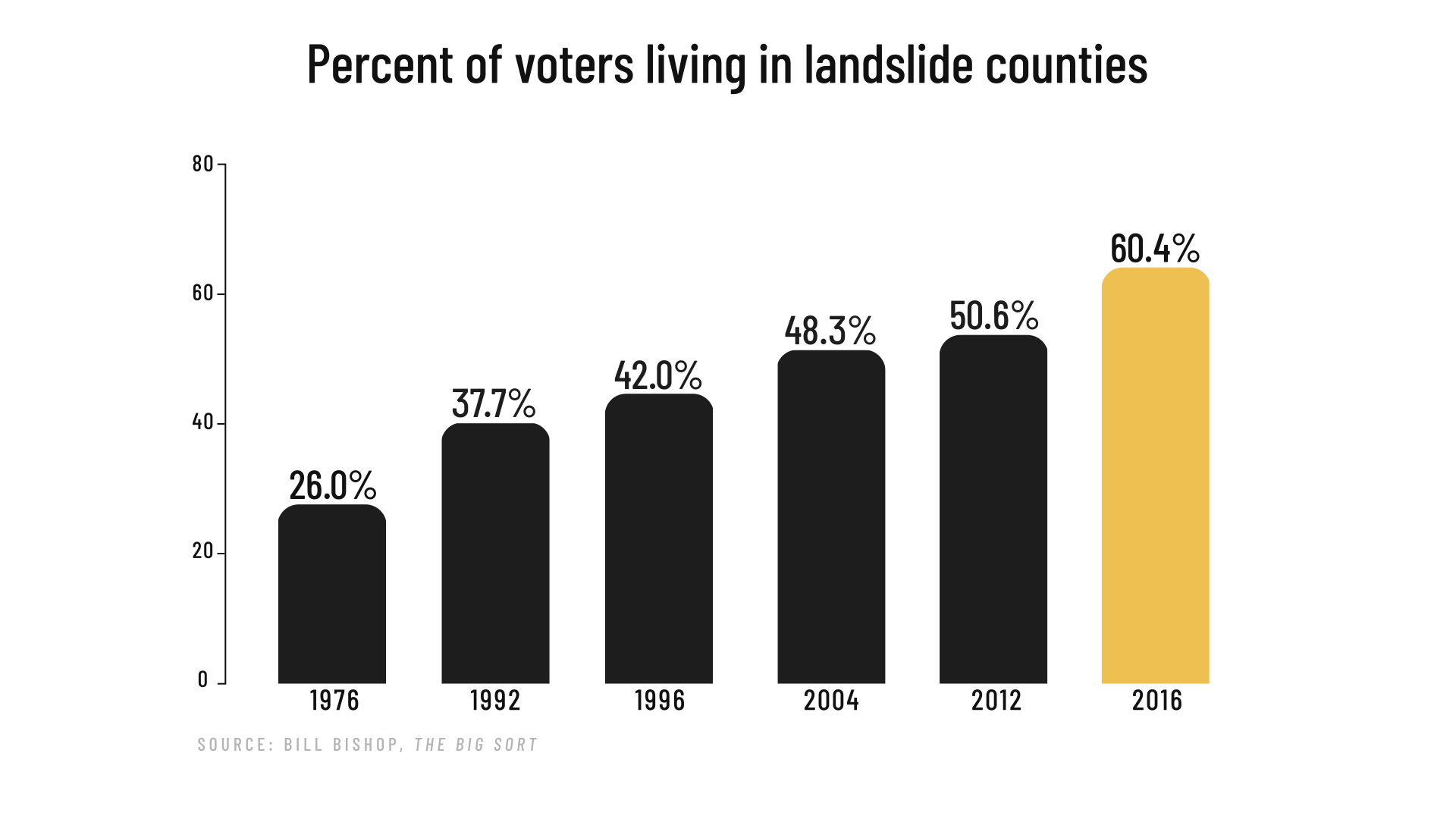

He and his wife had been taking polka classes long enough to know the move was out of the ordinary. And he’d even written a book about geographic self-sorting, noting the growth of the urban-rural divides over the last four decades. But in making the move himself, he was forced to contend with a hard reality: His Austin neighborhood was incredibly monolithic, and rather than inspiring him to rigorously question his worldview, it had been reinforcing it, over and over again.

But in taking the leap from one Texas county to the next, Bishop found inspiration again. Sure, he says, “There’s no Ethiopian restaurant and no movie theater.” But he and his wife have found a new church, joined a choir and are happily enjoying their easy access to polka.

Most of us are not Bishop, though. We are comfortably nestled in our largely blue or red districts, increasingly surrounded by like-minded individuals.

The partisan media arms race

Of course, it’s not all our fault — partisan media and the federal government bear some of the responsibility for division today. Prior to 1987, broadcast news was governed by the fairness doctrine. That doctrine “aimed to ensure balance by requiring time for opposing political views,” explains Avlon. And while it was in place, the three main television news networks — ABC, CBS and NBC — were bound to devote time to differing views on issues of public significance.

But the FCC rolled back the doctrine during President Ronald Reagan’s second term, arguing that many networks, rather than presenting all sides of provocative political issues, were simply not discussing those issues at all.

That controversial decision helped pave the way for partisan media to thrive.

And thrive it did. Radio waves, which had been dominated by music, suddenly made room for conservative talk radio — with Rush Limbaugh entering the national mix in 1988. Several years later, in 1996, both Fox News and MSNBC premiered. Fox’s founding CEO, Roger Ailes, a former Richard Nixon media adviser, helped shaped the network into a bastion of conservative ideology. And MSNBC, over time, evolved into a leading platform for liberal commentary.

Then, in the early to mid- 2000s, liberal news sites like Daily Kos and Raw Story and conservative news sites like Breitbart and Gateway Pundit entered the political fray. As Avlon writes, “The partisan media arms race was on. But what is good for ratings can be bad for the country.”

Outing ourselves on social media

This partisan media race became more complex with the rise of new media in the mid- to late- 2000s. While television news remains the leading source of news for most Americans — 49% of Americans report getting their news from television — digital news consumption (33%) and social media consumption (20%) have experienced growth in recent years, according to Pew Research Center.

Phil L., a Democrat in Pennsylvania, tells CNN that social media, in particular, has complicated the political discourse. “In the past, our political leanings were held relatively close to the chest. At least in the sense that we didn't profess our allegiance to party in a large group setting.” But now, so many people have “outed” themselves on social media, creating and reinforcing an us-vs.-them mentality.

And Phil’s read of the social media sphere is supported by new research. According to Christopher Bail, director of the Polarization Lab at Duke University, and other researchers, people have become so entrenched in their political views, particularly on Twitter, that little can shake them of their partisanship.

Even when they are exposed to contrary political opinions, they tend to cling to the ones they already have. This, Bail notes, is more pronounced among conservatives, who he posits “hold values that prioritize certainty and tradition, whereas liberals value change and diversity.”

But we can’t blame cable news and Twitter for everything

It’s worth asking here: Do you watch cable television news each night? Do you tweet your political views each day? The short answer to both is: probably not. While viewership varies, prime time cable news shows averaged an audience of just under 2 million in October, according to Nielsen data. And the average age of their prime time audiences was over 60.

And what about a medium like Twitter? According to a 2019 Pew survey, only 22% of Americans report using Twitter’s platform. And of the ones who do use Twitter, only 42% report checking the platform once or more per day.

In other words, much of broadcast and social media is consumed by a small segment of the population, who research indicates may already be more partisan in their leanings. So, the growth of these networks may only be activating the most polarized among us, while the rest of the population just flips the channel or scrolls to the next tweet.

The dark art of drawing political maps

To make matters worse, many politicians have figured out how to capitalize on these divisions. Author David Daley explains that gerrymandering, “the dark art of drawing political maps to favor one party,” has contributed to “an epidemic of minority rule nationwide.” And while gerrymandering has been a part of US politics for a while, Daley argues that Republicans outplayed their Democratic counterparts in the lead-up to the 2010 election, winning back state legislatures from Ohio to North Carolina.

This enabled them to redraw districts the following year and contributed to their gain of 33 House seats in the 2012 election cycle. (Democrats, in the intervening years, have caught on and deployed a similar redistricting plan in Maryland.)

Today, according to Bishop’s analysis, a majority of Americans vote in noncompetitive counties, where the outcome is predetermined by the polarized extremes. And the winners in these counties are motivated to continue to exploit the issues that most divide us.

Why? As Elizabeth Spiers, who runs a progressive digital strategy firm, told The New York Times, messages of unity simply don’t motivate voters on Election Day. “[N]obody takes time off work, gets in their car and drives to the polls to vote specifically for that,” she adds.

The America we want

While our nation’s leaders may have little incentive to promote unity and harmony, they are not the only ones with power. We have it, too, and as one of our readers — Michael L. of Maine — told CNN, “If you want to heal the divide, give the people you love precedence over politics. Love and respect will go a long way to heading off the rancor and personal attacks endemic in today's political environment.”

But love alone may not be able to overcome the institutionalized forms of division plaguing America today, and in Part III, we will explore several concrete solutions to this pervasive problem.