A hungry elephant roams the grasslands of Laikipia County in Kenya until he spots a sweet, yet problematic, snack: the fruit of an invasive cactus.

The endangered mammal stops and eats, but also ingests sharp spines that lodge in his mouth, stomach lining and intestine. Not only can this cause painful abscesses, but the relentless spread of the cactus here is attracting more elephants closer to human settlements where the prickly pests grow, causing a spike in human-elephant conflict.

Opuntia, or prickly pear, was introduced to Kenya by British colonialists in 1940s as a living fence, but has grown out of control in recent years, plaguing elephants and other wildlife, and tearing through ranches and farmland.

According to the Center for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI), the plant, known by some farmers as the “devil’s cactus,” has invaded more than 500 square kilometers of the 9,462 square-kilometer county.

Authorities and locals have been waging a war to control the runaway cactus for a few years, often using machetes, mechanical diggers, or insects that feed on the cactus, but with limited success. Now, new technologies such as biodigesters, drones and apps, have been introduced to try to control the thorny pest for good.

A prickly problem

CABI estimates that without management, 70% of Kenya’s natural pasture will be lost to various invasive plant species. Opuntia has proven particularly hard to manage. If hacked down or uprooted, even the smallest part of the plant can take root and grow again if left behind.

“It’s got these horrible spines which make control of it exceptionally difficult,” said Arne Witt, CABI’s Regional Coordinator in Kenya. “If you are removing the plant and you might drop a flower or a fruit, they will start growing.”

The cactus is further spread by birds and animals, such as elephants and baboons, who eat the fruit and disperse the seeds. Where the cactus is dense, it can prevent people’s access to their homes and livestock’s access to food, says Witt.

(Video courtesy of Gustavo Lozada)

A 2017 study Witt co-authored, found the cactus caused significant economic losses for almost half of the households surveyed in the county, due to their grazeland being stripped of its native grasses and the ill-health of their livestock.

“It’s occupying all the land, so it’s reducing the productivity of range land,” said Witt. “You a see a lot of livestock dying, a lot of blind animals.”

Biogas and bugs

Witt says that biocontrol will be the best way of managing the pest. That involves releasing cochineal insects that feed on the cactus, killing it off, but not spreading to any other plant species.

At the start of the 1900s, an area of over 40,000 square kilometers in Australia was affected by opuntia, before it was controlled with bugs.

But some people are finding new ways to use the plant, such as producing biogas.

“Part of the mechanical removal is we are installing a biodigester that will create biogas,” said Tom Silvester, CEO of Loisaba Conservancy, a wildlife conservancy and ranch located in Northern Laikipia.

Silvester says the biogas will be used to cook food in a kitchen for the conservancy’s anti-poaching patrols. “That will consume up to 600 kilos of opuntia plant a day and cook for between 20 and 30 men every day,” he adds.

When asked about the idea of turning Opuntia into a cash crop, Witt warns that putting value on the cactus could make it harder to control because people will want to keep the plant alive. Loisaba says it considers the biodigester a temporary measure before releasing cochineal insects.

Maps and apps

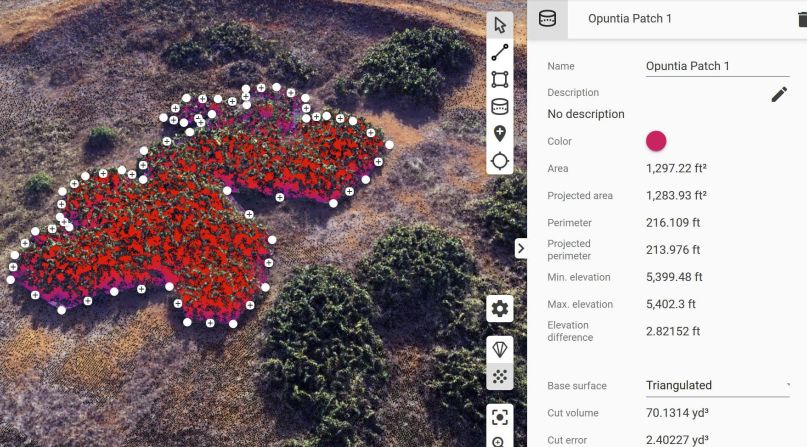

To monitor the success of the insects controlling the plant, Loisaba is using drones to map the spread of the prickly pear in areas inaccessible by foot or vehicle.

“Identifying areas of invasion, or ‘hotspots,’ is extremely useful in prioritizing and planning the conservation and management actions,” said Edward Ouko, of the Regional Center for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD) in Kenya.

RCMRD is working to map infestations of invasive species in Kenya and has partnered with Laikipia Wildlife Forum, Northern Range Trust and The World Agroforestry Center to develop a smartphone app, Invasive Species Mapper.

Using the app, farmers and members of the community can mark the locations of cactus clusters by taking a photo and uploading it with GPS coordinates to RCMRD’s database.

So far, their app has helped map an estimated 300 square kilometers of land, says Ouko. To overcome connectivity challenges in remote areas of Kenya, the app can be used offline, he says.

“Maps or information regarding the current distribution of cactus in Kenya is limited, making management decisions challenging,” said Ouko. “The models predict an increase in the rates of infestation over the next 50 years if no mitigation measures are put in place.”

“This invasion has numerous knock-on impacts,” said Witt. “It’s affecting the whole ecosystem in Laikipia.”

This story has been updated to add an image of the cactus in Kenya.