Editor’s Note: Ellen Gruber Garvey’s books include “Writing With Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance” and “The Adman in the Parlor.” She is a professor of English at New Jersey City University. The views expressed here are solely hers.

June 19 is the anniversary of the day in 1865 that black people in Galveston, Texas, belatedly learned from the Union Army that the Civil War was over and that they were freed. African-Americans have celebrated Juneteenth since 1866 as both a commemoration of freedom and a remembrance of the lies of whites.

The news that the war was over was withheld from Kossola, known in his American life as Cudjo Lewis, the subject of Zora Neale Hurston’s recently published “Barracoon,” as well. Although Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 10, Kossola’s owner, the brother of the man who had led the voyage to enslave him, failed to tell him that he was free. He learned it on April 12, from Union soldiers. The time lag was less dramatic than for the Galveston people, yet the theft of additional days of his life resonates in this account of a stolen life.

Between 1928 and 1931, Zora Neale Hurston spent months getting to know the last survivor of the last slave ship to land in the United States, and wrote up their conversations. The resulting work, “Barracoon,” has finally been published over 80 years later after spending decades in Howard University’s library. Hurston is best known for her groundbreaking novel, “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” but it is her training as an anthropologist – how her careful listening and writing preserved a record of a unique life – that enabled “Barracoon” to challenge the dominant, popular story of the Middle Passage and African enslavement in ways that still teach us today.

In Hurston’s conversations with Kossola, he emerges as an extraordinary and representative man who endured unimaginable horror, loss and trauma, who was robbed and disregarded, but who built up a family and community and endured. “Barracoon” brings him to the reader in conversation and relationship with Hurston the anthropologist and loving story hearer – eating crabs, offering peaches from his yard, photographed in his chosen clothing and stance. She needed and wanted to tell his story richly and beautifully, because for decades the story of the transatlantic slave trade had been told almost entirely by white people, who celebrated slave ship voyages as a way white youths became men. Their stories were part of the Lost Cause ideology. They have left their mark on American understanding of history. Hurston’s now-recovered story of Kossola’s life fought back against them.

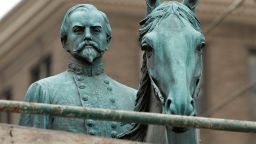

Hurston conducted her work at a time when, since the 1870s, American magazines had been publishing memoirs and stories by whites that made buying, transporting and selling Africans part of the same Lost Cause ideology that helped build Confederate monuments and generated textbooks glorifying slavery. It was part of the package that claimed that the Civil War was fought over states rights, not slavery, and that happy plantation life and Confederate honor and gallantry on the field were the real stories to be told repeatedly. By the time readers browsed through two or three such slave ship stories in Harper’s Monthly, Scribner’s or The Century, they assumed they were reading accurate reflections of events. Formulas have that power.

From the 1880s through the 1920s, such magazines published dozens of works that framed the Middle Passage as a site of white male adventure, ingenuity, derring-do, and of black invisibility. Some of the writers were ex-Confederate officers. Hurston complains in “Barracoon”: “All these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold. The Kings and Captains whose words moved ships. But not one word from the cargo. The thoughts of the ‘black ivory’ and ‘the coin of Africa’ had no market value.”

Hurston’s exasperation reflected her awareness that such narratives contributed to white supremacist myth making, which in turn gave rise to the movement to memorialize the Confederacy in monuments and statues across the South.

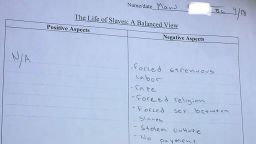

These formulas still have power. The myths of contented slaves and stories of Confederate battlefield courage as an absolute virtue, detached from the fact of fighting to uphold slave owning, continue to be told and believed. Generations have assumed “Gone with the Wind” is the true history of the old South. Students and parents have had to be vigilant to block textbooks that claim enslaved people were immigrant workers, as a 2015 McGraw Hill textbook asserted. How many editorial gatekeepers saw nothing wrong in that claim and let it be published? Even teachers imagine that there must be some truth to it if so many people say that slavery had its good points, so a Texas charter school teacher recently felt free to assign students to “list the positive aspects of slavery,” and the child whose parents objected is getting pushback from others at school.

Neo-Confederates have sought to rebrand white supremacy as just a form of history. In 2016 and 2017, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant could continue to proclaim April as Confederate Heritage Month in his state, despite objections, declaring that his intent is to have Mississippians “understand and appreciate our heritage.” The repeated assertion of these claims, in many forms, normalizes them and lets whites escape being made uncomfortable by the truth.

These slave ship accounts, like Wilburn Hall’s “The Capture of the Slave Ship Cora: The Last Slaver Taken by the United States” published in 1894 in The Century, are often set on a US Navy ship that seizes a slaver, after the official ban on bringing new slaves into the United States in 1808. Typically, they focus on the coming of age of a young white man, while the enslaved people on board are barely visible.

When Wilburn Hall is given command of the captured ship, he takes on the slave ship captain’s role, and accepts that his job is to transport the Africans as though they were cargo. The story suggests that there is only one possible role for a white man to take in relation to black people and makes clear that it is the relationship between different types of white men that matters, not the Africans’ lives. Like most magazines that published these narratives, The Century addressed well-off people; it made a specialty of rewriting the Civil War to focus on reconciling white North and South, in part to bring in more Southern readers.

White supremacist stories of the Middle Passage are now mostly forgotten. Anyone now might bridle at the claim those stories repeated that enslaving Africans was for their own good because it Christianized them. But when powerful formulas accomplish their work they leave their shadow in the enduring assumption that kidnapping and enslavement were like “voluntary immigration,” and there must have been something good in slavery.

If these narratives show white supremacist myth making in action, Hurston’s “Barracoon” exemplifies African-American resistance to it. Hurston reused parts of another Lost Cause slave ship account, Emma Langdon Roche’s 1914 “Historic Sketches of the South,” an account of the “last slave ship,” when she first wrote about Cudjo Lewis/Kossola in a 1927 article. In terms made familiar in decades of writing about the adventure of sailing slave ships, Roche celebrates the ship owners’ adventure-seeking cunning and daring as they shaped the 1859 slaving expedition that captured Kossola. Hurston’s biographer, Robert Hemenway, in 1980 slammed Hurston’s use of it as plagiarism. But Roche’s text also attacks black people as “the wildest barbarians” and defends the Ku Klux Klan, so perhaps Hurston felt justified in taking over bits of the book to undermine them, and to force it to tell something closer to the real story of a man stolen from his land and family.

Kossola, in his conversations with Hurston, frequently interposes the phrase, “you unnerstand me.” The phrase reaches out to the reader: Could we possibly understand him? For Hurston, talking to Kossola was the last chance to listen to someone who lived through the Middle Passage. The question punctuates the narrative. None of the white writers of Lost Cause slave ship accounts had the slightest concern about whether their readers understood the Africans on board. Hurston saved her conversations with Kossola, and subverted the formula.

“Barracoon’s” publication was delayed for many reasons, most notably because Hurston refused to tailor its language or meaning to the specification of her white editors. The book’s appearance now lets us see it apart from the early 20th century world that produced it and the later 20th century readings that discounted it. Kossola’s complex human voice finally emerges from the noise of stories that put white sailors first.