The United Kingdom has expressed “concern” over the Hong Kong government’s proposed use of a colonial-era law to ban a pro-independence group.

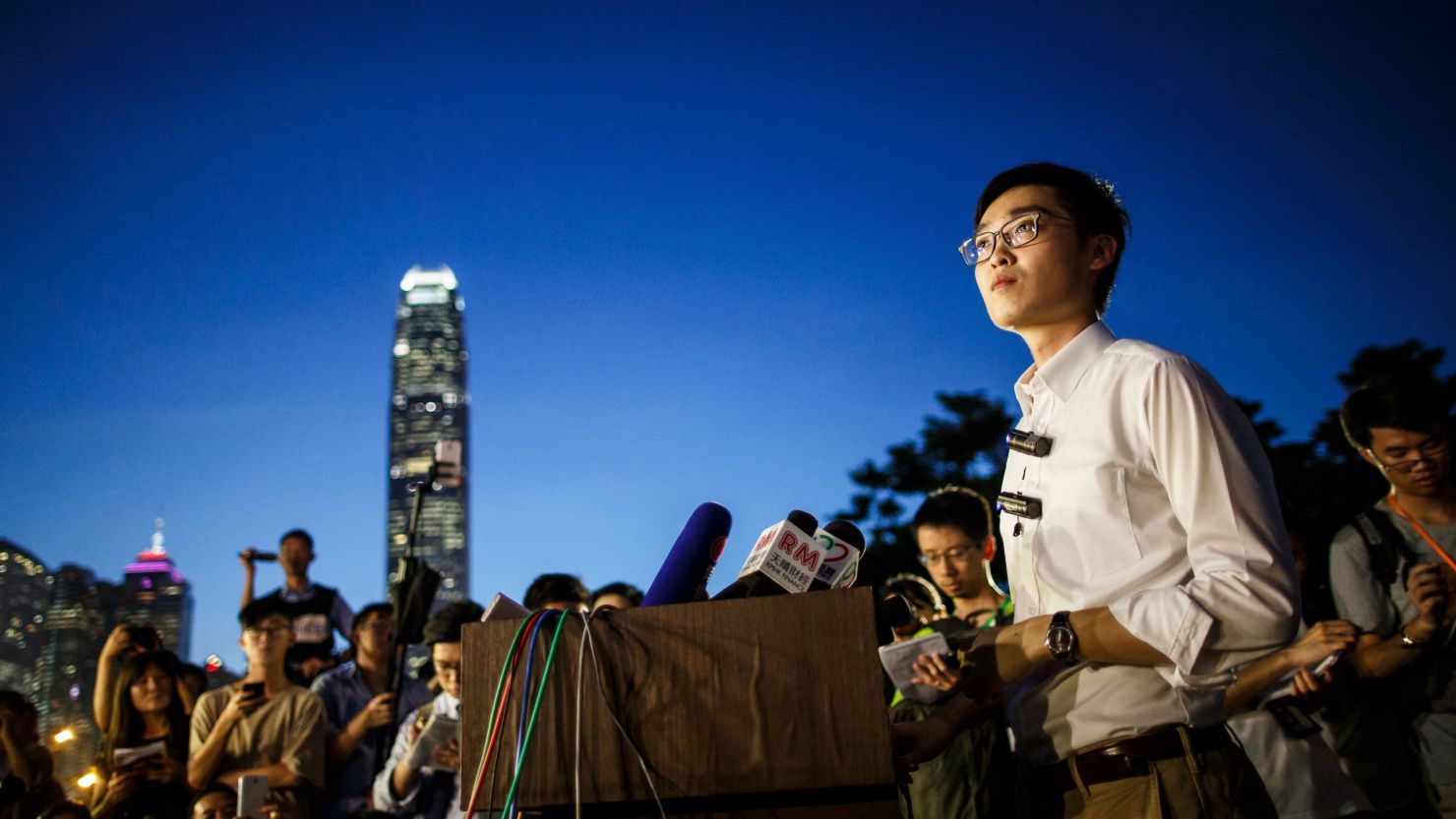

Hong Kong National Party (HKNP) convener Andy Chan said he had been served with documents by police Tuesday stating they were recommending his organization be banned under the Societies Ordinance, which has never before been used to prohibit a political party.

In a statement, the UK Foreign Office said while it “does not support Hong Kong independence,” the city’s “high degree of autonomy, and its rights and freedoms, are central to its way of life, and it is important they are fully respected.”

Under the ordinance, if HKNP is banned it will be illegal to be a member of the party, act on its behalf, or raise funds for it. Offenders could face up to three years in prison and fines of up to $12,000.

Hong Kong’s secretary for security John Lee told reporters Tuesday that HKNP had 21 days to explain why he should not issue a “prohibition order” against it.”In Hong Kong we have freedom of association, but that right is not without restrictions,” Lee said, adding the HKNP could be banned “in the interests of national security.”

It was not clear what the specific concerns related to national security were.

Amnesty International researcher Patrick Poon said the move had “potentially far-reaching consequences.”

“To use sweeping references to ‘national security’ to silence dissenting voices is a tactic favored by repressive governments,” he said.

“Under international law and standards, any prohibition of an organization is subject to a strict test of justification, with the burden of proof on the government to demonstrate that a real, not just hypothetical, danger to national security exists.”

Pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong said the threat showed “we have entered a new era of white terror, where anyone’s thoughts and words could condemn them with a criminal charge.” Wong has been jailed in the past on what some observers said were politically motivated charges.

During Taiwan’s “white terror,” tens of thousands of government critics and opposition activists were arrested and thousands executed.

“In the past few years, the Hong Kong government has used the excuse of protecting national security to manipulate administrative procedures to suppress dissidents, such as suspending company registration procedures for certain political parties and the disqualification of candidates,” he said in a statement released by his party, Demosisto.

‘Far-reaching consequences’

Founded in 2016 to advocate for Hong Kong’s independence from China, the HKNP has already faced restrictions on operating. Chan was one of several separatist candidates barred from standing in 2016’s legislative elections, and the group has also struggled in the past to get police permission to hold rallies or protests.

Support for Hong Kong independence and greater autonomy from China has grown as Beijing has increasingly encroached on the city’s freedoms and promised political reform has not panned out.

However, Chinese leader Xi Jinping warned during a visit to the city last year that it was a “red line” for the central government.

Chan told CNN he expected “more political organizations” may face bans under the ordinance. “This is the beginning,” he said. “The world better keep a close eye on this.”

The Societies Ordinance has been widely criticized for being overly restrictive. In 1992 the last colonial government of Hong Kong amended it to bring it in line with international human rights law, but this move was reversed once China assumed control of the territory, one of several liberalizing reforms thrown out by the provisional legislative council, an appointed body stacked with pro-Beijing figures.

Last month, Chris Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, criticized the use of another colonial era law, the Public Order Act, to convict pro-independence activist Edward Leung.

“We attempted to reform the Public Order Ordinance in the 1990s and made a number of changes because it was clear that the vague definitions in the legislation are open to abuse and do not conform with United Nations human rights standards,” Patten said in a statement.

“It is disappointing to see that the legislation is now being used politically to place extreme sentences on the pan-democrats and other activists.”