“Three Identical Strangers” is available now on demand. Learn about the science behind the story in the “Three Identical Strangers” podcast.

Six hours before his flight to the first shoot of “Three Identical Strangers,” director Tim Wardle wasn’t sure if he had a film at all.

He and his team had spent four years working on their stranger-than-fiction documentary, about triplets separated at birth and reunited 19 years later, and they were finally ready to start shooting.

Then those plans came to an abrupt halt.

“We were all packed in London and ready to go to the airport,” Wardle recalls. “And some of the people involved pulled their funding. We were left there thinking, ‘Is this happening, or not?’”

You don’t need a spoiler alert for what came next. Wardle ultimately found support for that first shoot and “Three Identical Strangers” was on its way. The film released in select US theaters last summer to critical acclaim and picked up plenty of buzz as it became one of the top grossing documentaries of 2018.

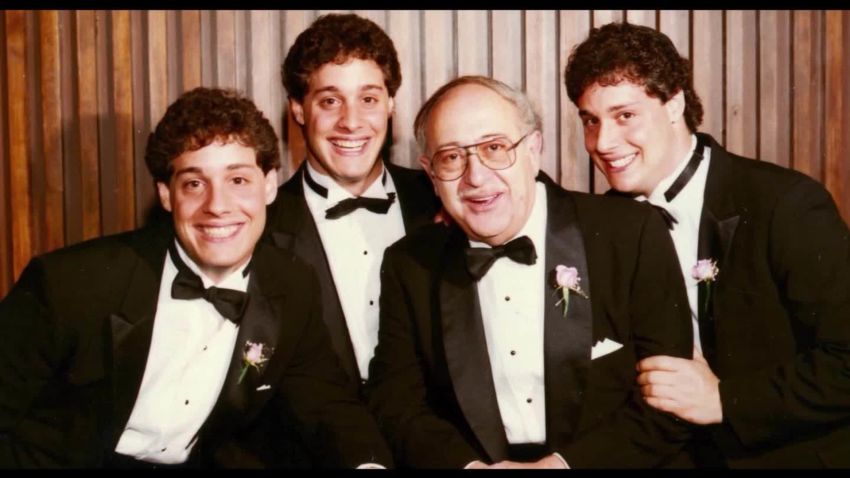

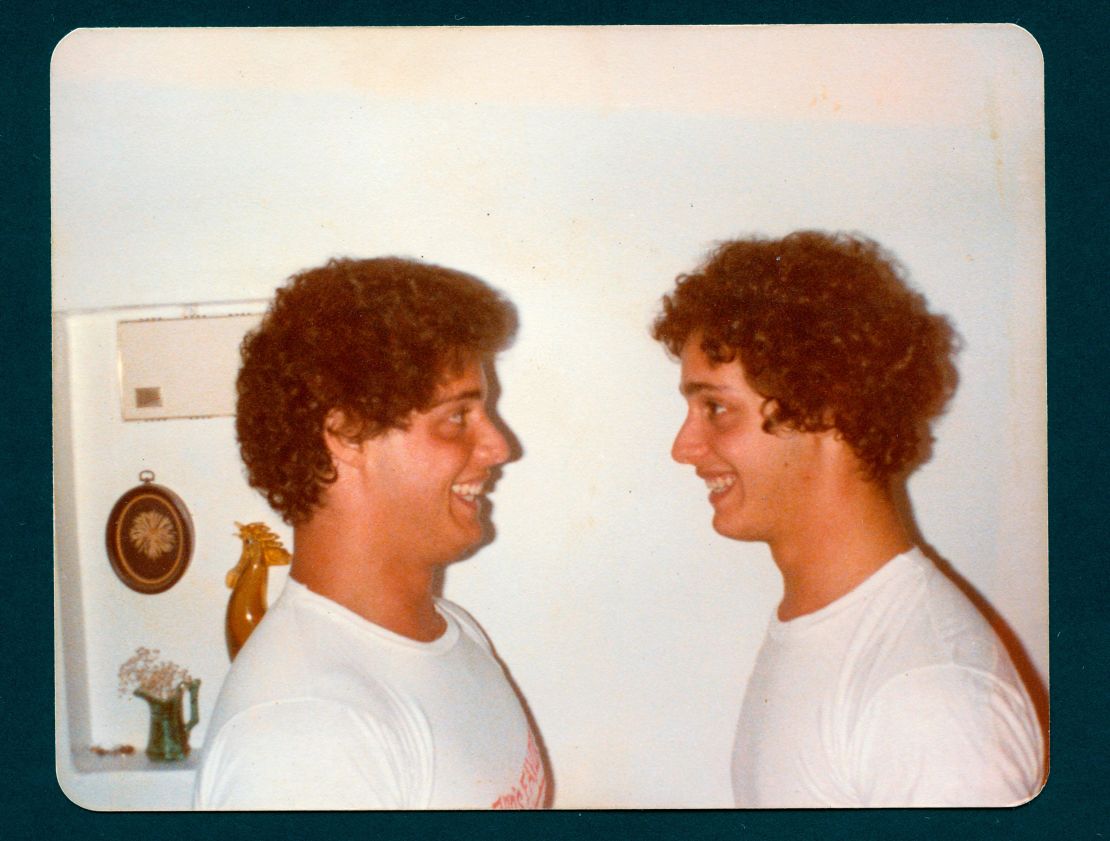

The film starts with the 1980s reunion of Robert Shafran, David Kellman and Eddy Galland, who learn they’re triplets after a “Parent Trap”-worthy mix-up on a college campus. But the question of why the brothers were separated in the first place opens the door to an unsettling secret – a reveal just as astounding as the story of how they met.

To tell the full story of what happened to the triplets, Wardle and his team had to face a few plot twists of their own.

“There were at least three or four moments where I think everyone on the production thought, ‘This is going to fall down, this whole thing is going to fall apart,’ ” Wardle says. “It’s kind of a miracle it got made.”

The crew behind “Three Identical Strangers” explains how that documentary miracle came to pass.

These responses have been edited for length and clarity. If you haven’t seen the film and don’t want to know what happens next, stop here, make a bookmark, and we’ll see you when you’re caught up.

Robert “Bobby” Shafran, one of the triplets: “I was coming from court one day and I was driving and I picked up the phone, and this Londoner said, ‘Hi, is this Bobby? I’ve just gotten your number from your stepmom.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, why’d she give it to you?’ And she said, ‘I’m a documentarian and I’m interested in doing a feature documentary.’”

Grace Hughes-Hallett, producer: “There were no contact details online for either Robert or David. And I live in London, so I couldn’t just go find them and knock on doors. I managed to find Robert’s dad and stepmom and I cold-called them.

“What I was immediately surprised by (was that) I thought I might be speaking with him about a moment in his personal history. Obviously, his reunion with his brothers was decades ago, and finding out what happened to them was decades ago. But very quickly through speaking to him on the phone I realized this was still a huge part of his day-to-day reality, and he was still actively searching for the truth. This wasn’t just kind of a retrospective thing for him, it was an ongoing story.”

David Kellman, one of the triplets: “Bobby and my relationship was pretty fractured for quite some time, but we spoke about it.

“We were always able to talk … we just didn’t make a big effort. We’d get together and then there wouldn’t be any follow-up. We had separate lives, and we’d gone through a lot.”

Hughes-Hallett: “That’s a crazy enough story to have about yourself as it is, that you were separated at birth from a twin or a triplet. The boys’ story had a whole other level of craziness on top of that, in the way that they found each other. And then the awful things that began to unravel as they discovered what really happened to them.”

Tim Wardle, director: “(Grace) and I spent two years trying to sort of flesh out the story and try to get funding for the project. But the single biggest hurdle to making it happen was earning the trust of the brothers. When you think about the extent of what they’ve been through and what’s happened in their lives, you understand why they might find it hard to trust people.”

Shafran: “We were really reluctant for a lot of reasons, the most obvious being the typical American’s perspective on British sensationalistic newspapers. They could sensationalize the crap out of this.”

The brothers, born in New York in 1961, were separated by adoption agency Louise Wise Services. Their adoptive families had no clue that each son they brought home had been born as a triplet.

The brothers, along with other multiples who were separated and sent home with different families, were then secretly included in a years-long study by child psychiatrist Dr. Peter Neubauer. The results of Neubauer’s study were never published, and the study’s materials are being kept under seal at Yale University.

Wardle: “When we first started to work on this story, there was media around their reunion in the 1980s and there was a tiny bit later in the ’90s. But apart from that, there was nothing. We really had to piece this together and put it together from scratch. It was a lot of persistence and old-fashioned journalism, knocking on people’s doors. It wasn’t the kind of story you could research looking on the internet.”

Becky Read, producer: “The first thing I did was have a really long chat with Robert and David, and the key family members. The other part of it was constantly trying to find people from the (Louise Wise) adoption agency and from the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services (where Neubauer worked).

“There’s such a sense of injustice about what happened to these boys and their families … all of these families had been tricked, and there’d been a cover-up.”

Documentary filmmaking is a marathon, not a sprint. In between working with the brothers and securing funding, they were turning over every hint of a lead they could find. It wasn’t long before they made a disconcerting discovery.

Wardle: “People had tried to tell this story before; we learned of at least three attempts by major US networks, two in the ’80s and one in the ‘90s. In each case, we spoke to people who’d been involved in those projects and they told us they got a long way through getting it ready to go … and it had been pulled at the last minute by people higher up.

“There was a huge amount of paranoia … people (were) telling us, ‘There’s no way you’re going to be able to make this story, you will get shut down, it will get pulled.’ As Lawrence Wright says in the film, there are loads of powerful people who want this story to be silenced, and I feel that’s true.

“We know the individuals involved in setting up the experiments and the study were very well connected; we found documentary evidence when we were making our film. It became clear at that point that this wasn’t just in theory, this was real.”

Read: “We were lucky, I think, in that a lot of the people had passed away. But it still didn’t stop Tim and I from being worried.”

Wardle: “I think a large part of making the film was just trying to stop ourselves from getting paranoid.”

Read: “I went to Columbia University archives and loads of other archives in New York, and literally just sat in libraries to look through pieces of paper to find names of people who’d worked at the adoption agency. Then I came back to London with a list of 200 names and I just started phoning them all. It was a case of, ‘Who’s dead? Cross that name off the list.’ Or, ‘Is their wife or husband alive? Did they keep a diary, or have they got records from the adoption agency?’

“You have to put as many irons in the fire as possible and follow those leads. That can be soul-destroying, because people don’t answer the phone, or don’t reply to your letters, or shout at you. You know people don’t want this story to be told. So you come up against dead ends and no one calls you back – until eventually somebody does and things slowly start to gather.”

Wardle: “The breakthrough moment with the brothers was the first day they came in and sat down for an interview (in 2017). It was one of the first things we filmed and we had no idea that they were actually going to turn up. But once they did sit down, they were emotionally open and honest about what happened.”

Kellman: “You just get a sense from people. When it became a level of trust, we were all in. … A lot of the stuff was done from the hip.”

Shafran: “Somebody asked me how many takes it took for the opening scene, and I was like, ‘uh, one?’ Everything was very, very real.”

Michael Harte, editor: “We were blessed with Bobby and David; they’re such good storytellers. I’ve been in edit hell before with other projects, but this wasn’t like that. Anytime you got tired, or anytime you got frustrated – at no point did I ever think, ‘What are we doing this for?’ We really believed in it, and we believed in the story we were telling. They were handing over their life to us.”

After putting up a fight for their records from Neubauer’s study, the brothers won access to boxes of material that otherwise would have been sealed at Yale University until 2065. That includes material pertaining to their brother, Eddy, who killed himself in 1995.

Read: “When I came on board and was looking for the study, I found a reference to Yale University in the archives. You see David in the film looking at this website; he’d never seen it before. That’s him genuinely going, ‘Oh my God, there’s 66 boxes of it.’

“We started a conversation about the records and access to them. We were denied initially, (but) we kept at it.”

Wardle: “We were driven by the injustice on the behalf of the brothers. Becky spent nine months working with the brothers to access the material; they had to speak to a lawyer hired by the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services … to get access to files and footage that should rightfully be theirs.”

Read: “The problem was the deadline for the film. We pushed back our schedule a number of times (but) you can’t film forever. We were juggling a lot of pressures, and my job was just to keep the pressure on the Jewish Board.

“We’d finished the film and had suddenly gotten (almost) 11,000 pages of records. We had to have a conversation about what was in there and whether we should go back out and film, and somebody had to know what all that stuff was to make that decision.

“I sat and read these 11,000 pages. It took me about a week, just locked in a room reading. I think we felt that the film was finished and was good, and we weren’t sure whether this stuff would benefit it. And there’s a huge amount of personal stuff in those records that are private for a reason; Robert and David’s privacy, and their family’s privacy, was important. Moving forward, anything that’s released from there is for them to release.”

Kellman: “The people who put this together are all gone. The people who made these decisions are gone; some of the people who funded it may still be alive. It’s kind of like sins of the father. Is there ever going to be complete closure? Nah. Can’t be.”

In the end, “Three Identical Strangers” covers a lot of themes: medical ethics, mental health and the question of nature vs. nurture among them. But for some, it really boils down to family.

Wardle: “I think it’s the toughest thing I’ve done. The thing I’m proudest of is that ‘Three Identical Strangers’ has had a real-world impact. We managed to get the brothers access to files and videos that have been kept secret from them for six decades. We know of at least one twin pair who have reunited after seeing the film. (And) it has brought the triplets and their families much closer together.”

Shafran: “Where we are (now) is such a positive place. It’s priceless. The film pales in comparison to the rest of our lives together. I mean, I hope it does great. (But) it wasn’t just making the film; we were only together for one scene.”

Kellman: “It’s given us perspective in terms of time lost being estranged. And it’s brought us incredibly closer. We’ve spent an awful lot of time together; we played golf 14 times throughout the spring and summer. We speak frequently. That was the most valuable thing that came out of this film.”