Editor’s Note: Lisa Marie Daunt is a PhD Candidate in Architecture at The University of Queensland. The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the writer. CNN is showcasing the work of The Conversation, a collaboration between journalists and academics to provide news analysis and commentary. The content is produced solely by The Conversation.

In the post-war decades, Australian communities invested heavily in churches. Like civic centers, swimming pools and shire halls, these buildings made an important contribution to the formation of a modern civic realm in Australia’s growing cities, suburbs and regional communities.

Today, dwindling numbers of constituents and the amalgamation of congregations have placed many post-war church buildings at risk. And yet – unlike their publicly funded counterparts – these structures are largely ignored in discussions around architecture and conservation. Few churches enjoy any form of heritage protection. Could this be because they represent an “uneasy heritage”?

Given current crises affecting churches in Australia, and given the important role these buildings played in the post-war development of the country’s cities, suburbs and towns, a public debate is necessary about their future. Should we allow these buildings to disappear from memory, or should they be preserved or repurposed?

Across Australia, only about 30 post-war ecclesiastical buildings have been included on state heritage registers. It’s a meager number, given that several thousand churches were built across the country during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

In Queensland alone, over 1,000 were built between 1945 and 1975. Of these, only six are on the Queensland Heritage Register.

Mirroring modern Australia’s emergence

In the immediate post-war years, modern church-building in Australia made a hesitant start. A few small, rather conventional structures began cropping up.

In the 1950s, however, hesitation gave way to optimism, resulting in increased experimentation. By the 1960s, a genuine modern church boom was under way.

Religious institutions strongly supported the Australian government’s bid to build a modern welfare state. As such, they not only built community-oriented churches, but also kindergartens, halls, primary and secondary schools, charity outreach centers and hospitals.

From the 1960s, churches and their architects increasingly recognized the need to rethink ecclesiastical architecture, in order to cater to (rather than ignore or shun) modern society. This “aggiornamento,” or bringing up to date, in the religious sphere coincided with architects’ experiments with modern materials, new construction technologies and innovative shapes and forms.

As a result, a new “type” of church emerged. It was one more attuned to its (commonly) residential surroundings, and more sensitive to its context, both in terms of materiality and scale.

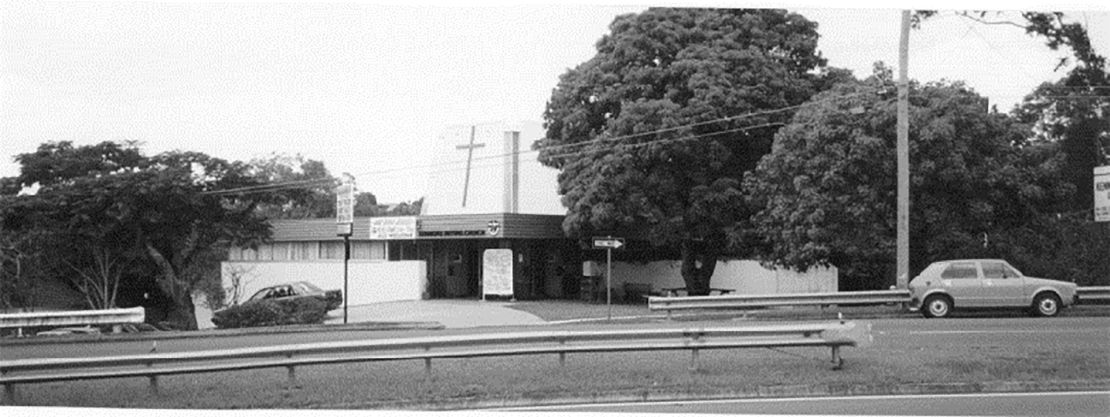

Examples abound from the 1960s, but of note are Kenmore Presbyterian Church (now Uniting Church) in Queensland; St Anne’s Church of England by in Como, New South Wales, which was repurposed as a private residence in 1997, along with its Sunday school building; and St Christopher’s Catholic Church, which was damaged in 1983 bushfires and rebuilt to a revised design the following year.

These smaller, contextually sensitive structures – designs that reflect the “aggiornamento” of the church – represent the bulk of post-war modern church buildings in Australia. However, state heritage registers are mostly populated by their more “monumental” siblings.

And yet it is the smaller, unassuming churches that made the greatest contribution to the formation of our post-war collective realm. More importantly, it is these churches that are under the greatest threat.

So, what is to be done? Is this part of our modern heritage best forgotten, along with the (at times) painful memories it evokes? Or can there be a future for Australia’s unassuming post-war modern buildings that were once the beating hearts of the country’s urban and suburban communities?

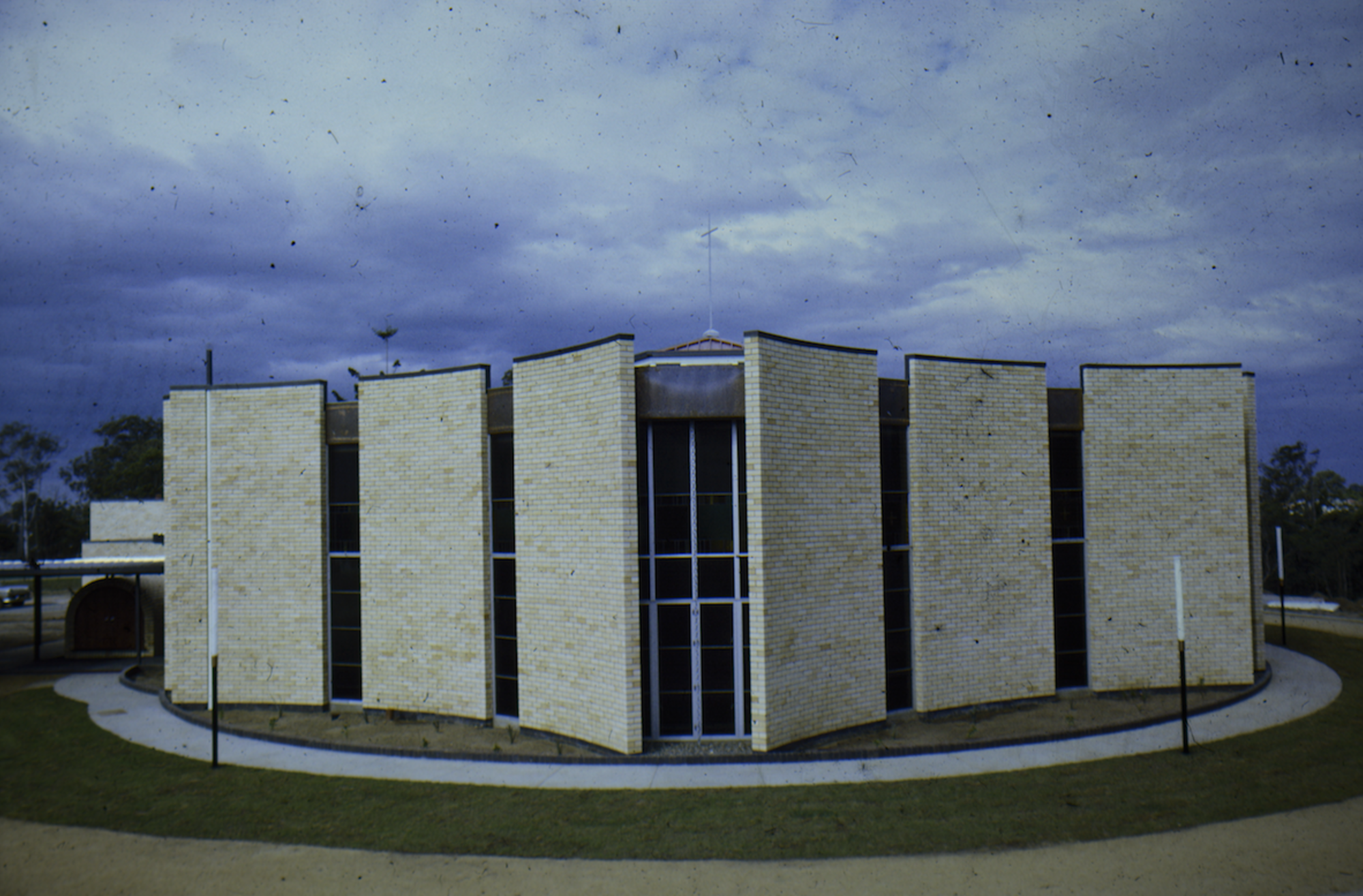

Top image: Good Shepherd Chapel in Mitchelton, Brisbane, which was demolished in 2004 (Ian Ferrier Slide Collection).

Republished under a Creative Commons license from The Conversation.