“As good as we can be as scientists, we are not the guys who are living in it 24 hours a day, who will have perceptions that go beyond the couple of hours or even the months or years you might attend to something as a scientist," says Rouja.

Combining scientific research with local knowledge is the cornerstone of his strategy for conserving Bermuda's shipwrecks.

He admits that it's often too easy for scientists to get caught up in data, but "the wholeness of a story that includes a local perspective resonates across a much broader spectrum than a purely professional or a purely academic one."

As a prime example of this, Rouja pulls out a weathered scroll of paper from his office.

It's a map, hand-drawn by Teddy Tucker and annotated with notes on fish populations.

Most notably, it highlights the stark changes in the marine environment over the last half-century.

"Teddy's talking about fish that I know I've never seen, but he's also talking about sharks," laments Rouja.

"I think these were things that were just a common feature of the marine environment around Bermuda, and, you know, they're just not here. You don't see sharks. You just don't see them, and so it's obvious that things have changed dramatically when something that's that ubiquitous to a reef area is just absent."

This type of local knowledge has informed Bermuda's efforts to revive numerous fish species and promote healthy reef ecology.

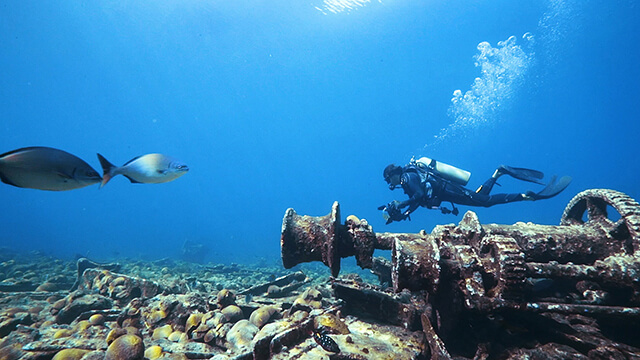

By protecting the shipwrecks and restricting fishing nearby, the government has simultaneously created ideal conditions for depleted fish populations to recover.

One such species is the Stoplight Parrotfish.

"The shipwreck led us to focus on its spawning aggregation," says Rouja, referring to when a species of fish gathers together in greater densities than normal with the specific purpose of reproducing.

"And the cool part is that the protection we afforded to the shipwreck included this aggregation, which essentially created the circumstances or helped support the circumstances for that aggregation to flourish."

As Rouja continues, it becomes even clearer that everything is connected.

"Parrotfish are very important for grazing on the reef and the rocks and they graze down the algae. And algae, if it's not controlled, overtakes our reef," he says.

"The loss of those algae controlling fish has been very significant. So suddenly I'm on a shipwreck where I can catalog the history, we can look at growth over time of reef on that shipwreck because that shipwreck sets a date and time that allows us to look at coral reef growth, and at the same time, it has accidentally protected the spawning aggregation of Parrotfish."

In this way, Bermuda stands on the forefront of an innovative new trend in environmental conservation by including shipwrecks in marine protected areas.

With its relatively small landmass, limited natural resources and a population accustomed to the luxuries of western society, Bermuda presents a microcosm of the environmental challenges faced by much of the world.

"Whatever we import we have to dispose of," Rouja remarks. "It doesn't go to some other county a couple hundred miles away. You know if we discover a source of pollution we can't just sort of isolate it and push it to an area we don't have to deal with it. It's always here."

Bermuda's integration of cultural and environmental heritage preservation by embracing local knowledge is an example of one way governments can tackle conservation issues like these.

As Rouja puts it, "the more I can integrate shipwreck conservation with environmental conservation, the stronger the case will be for both."

For a place that cares so deeply for its culture and traditions, Bermuda's willingness to adopt new and creative solutions to maintain its identity in an ever-changing world sets it apart.

There is a sense of hope on the islands, a place where even castaways forced to pillage from a sunken ship can endure.