It was meant to be the first Games to be held beyond Europe and North America, a spectacle to showcase to the world that Tokyo had overcome the earthquake that had devastated the city some years earlier. But the 1940 Olympics was the Games that never was.

No one aged under 80 had ever lived through a time when the Olympics was postponed or canceled until Tuesday’s announcement that Tokyo 2020, originally scheduled to start this July, will now be held next year.

As a pandemic takes hold of the world and the International Olympic Committee and Tokyo 2020 organizers grapple with the complicated logistics involved in holding the greatest show on earth later than planned, a look at the past throws up some uncanny similarities between now and what has been described by some as the Lost Games of 1940.

Glory on the world stage

Before the 2020 Olympics was postponed, sport’s biggest extravaganza has been called off three times in modern history, all in wartime, and the last time being the year Tokyo was supposed to be the host city.

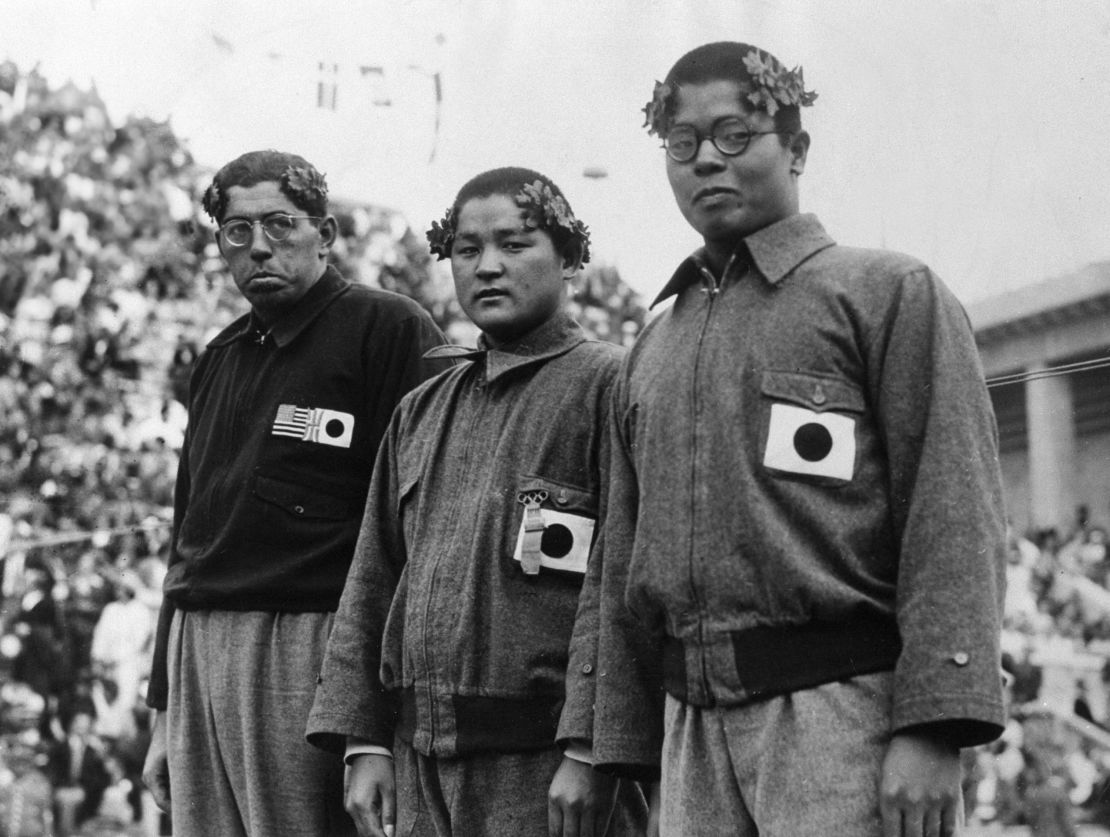

It was the success of Japan’s athletes at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles and international criticism of the country’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931, as the Japanese empire continued to expand into China, which helped persuade the country’s government to fully support an Olympic bid, something which had previously been the preserve of elite cities in the west.

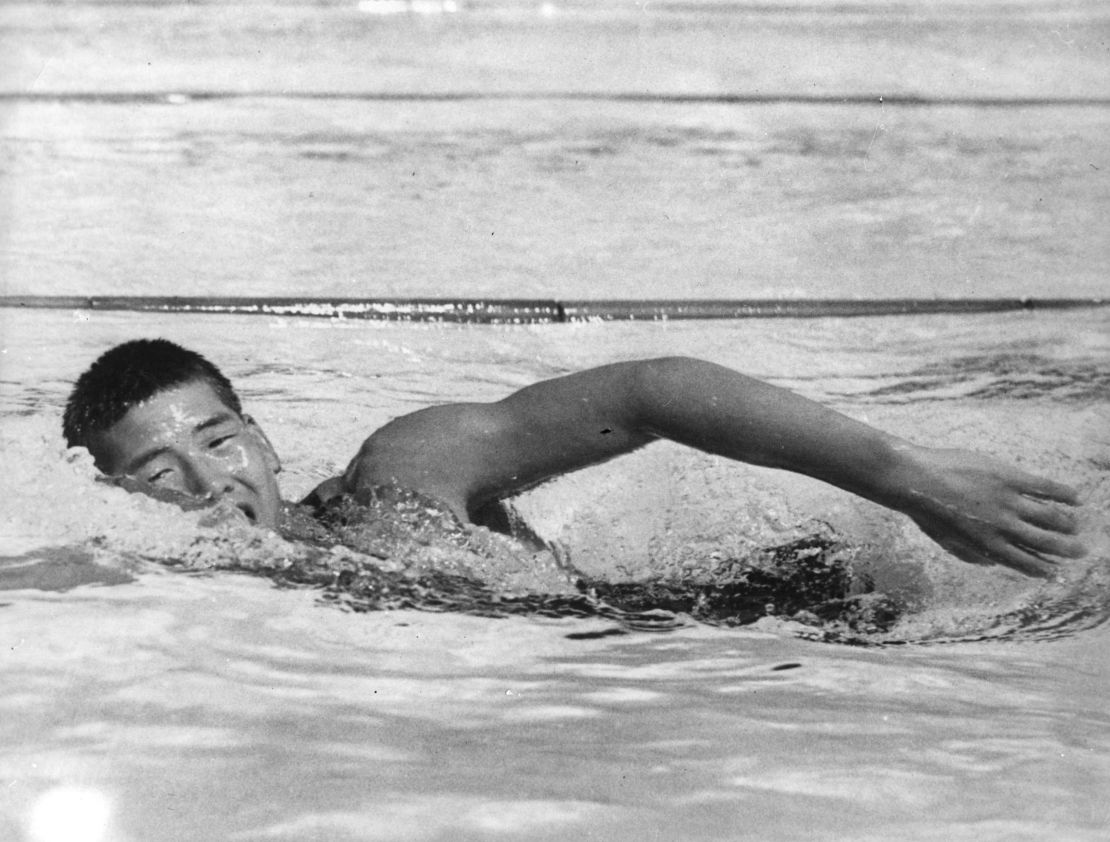

Japan’s male swimmers had dominated in LA and, as David Goldblatt writes in his book “The Games”: “The correlation between international prestige and Olympic achievement … made the idea of a Japanese Olympics first plausible, then desirable and, finally, an essential element of foreign policy.”

Just as the 2020 Olympics were billed as the “Recovery Olympics” nine years after the Fukushima disaster, Nagata Hidejiro, the mayor of Tokyo, had first announced in 1930 a bid for the 1940 Games, envisioning the Olympics as a way of aiding the city’s recovery from the earthquake of 1923, which had destroyed much of the metropolitan region.

An Olympics in Tokyo in 1940 would also coincide with the 2,600th anniversary of Emperor Jimmu’s mythical accession and the foundation of the nation. Goldblatt described it as the “perfect notion around which to build support for a Japanese Olympics in an increasingly nationalist culture.”

The campaigning begins

In the 1930s, Japan had Olympic pedigree. In 1912, it had become the first non-European/American country to participate in the Olympics and, significantly, also had delegates on the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

“Japan had been agitating to hold the Games in the early 1930s,” William Kelly, Sumitomo Professor of Japanese Studies at Yale University, tells CNN.

Judo pioneer and IOC member Baron Jigoro Kano is widely believed to have played a major role in Japan’s bid, giving a keynote speech to the IOC at the end of the 1932 Games.

According to the IOC leader of the time, Henri de Baillet-Latour of Belgium, Kano told those in the room that holding the Games in Japan would extend the vision of the movement’s founder, Pierre de Coubertin, and bridge the gap that existed between the East and the West.

In this context, the 1940 Olympics was “instrumental in legitimizing the IOC rhetoric that the Olympic movement was universal,” writes Dr. Sandra Collins in her book “The 1940 Tokyo Games: The Missing Olympics.”

While liberals had visions of a global festival, Japan’s government saw the benefits of hosting the Olympics differently, as an opportunity to influence a world dominated by the west.

In the first half of the century, the country was committed to maintaining and strengthening its position as its region’s lead and during the Great Depression there was a growing belief that Japan would solve its economic problems through military conquests.

But Tokyo was not guaranteed to win the race to host in 1940. Rome and Helsinki were the city’s main rivals, with the Italian capital regarded the favorite.

So in 1935, Japan’s IOC member Sugimura Yataro traveled to Italy to visit the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini to ask Rome to withdraw its bid.

“In the you-scratch-my-back kind of deal that has become the norm in international sports politics, Mussolini announced with usual candour, ‘We will waive our claim for 1940 in favour of Japan if Japan will support Italy’s effort to get the XIII the Olympiad for Rome in 1944,” writes Goldblatt.

The significance of 1936 Berlin

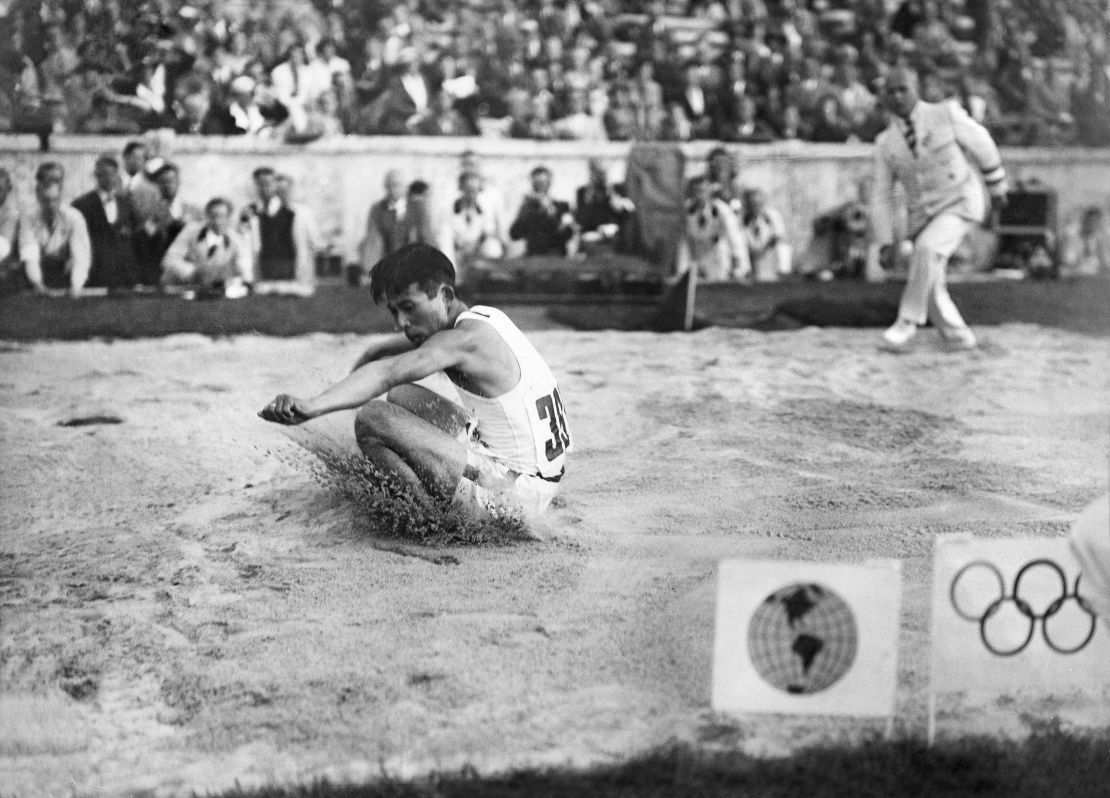

During the conclusion of the 1936 Olympics, the Games that had been the Nazi power show, the IOC awarded 1940 to Tokyo, with the Japanese capital receiving 37 votes to Helsinki’s 26. Four years after Nazi Germany had hosted the Olympics, Japan – a country already regarded as an imperial aggressor – was set to also have its time in the sporting limelight.

And in 1938, a year after Japan had invaded China, the IOC awarded the Winter Olympics to the Japanese city of Sapporo.

But that same year, with major countries threatening to boycott as Japan’s ferocious destruction of Chinese cities was reported in the American and European press, the Japanese government forfeited the right to host both the Summer and Winter Olympics.

Embroiled in a war with China and knowing a global conflict was on the horizon, the military government passed the National Mobilization Act.

“Three months later, with little fanfare, the Japanese pleaded the need for ‘the spiritual and material mobilization of Japan,’ and relinquished the 1940 games,” writes Goldblatt.

“The suspension can’t be separated from the 1936 Olympics,” reasons Kelly. “The Americans, the British and French started talking about boycotting the 1940 Olympics because they felt they had been badly used by Hitler in staging this enormous propaganda Games so it was really the Berlin Olympics effect that caused the Japanese government to withdraw its bid. Japan knew it would be worse to put on the Games without the major powers.”

The IOC proceeded to award the 1940 Games to Helsinki, but the Soviet Union’s invasion of Finland in November 1939 ended any hope of holding an Olympics that year. Much like in 2020, the IOC held on in hope until succumbing to the inevitable.

Kelly adds: “The IOC said the world is increasingly at war but the Games will go on … [but] bowed to the reality that Europe was in flames and so was the rest of the world and they canceled the games all together.”

The cost of canceling

Tokyo’s preparation for the 1940 Games had been “quite considerable,” says Kelly, with significant economic investment made on infrastructure projects, such as transportation, sanitation and the building of hotels.

“The local businesses that had been persuaded to invest heavily in facilities, in providing goods and services for the Games found themselves without a prospective customer base, so the business community was upset in Tokyo but this was at a time when you could not really express anger at the government,” explains Kelly, arguing the country suffered more politically than economically in 1940.

“You’re not able to use the largest mega event in the world in order to demonstrate to the rest of the world what a great country you are,” he adds.

As the impact of postponing Tokyo 2020 is calculated, it’s worth remembering that the Olympics in the 1920s and 1930s were a different animal to the billion-dollar movement we are familiar with today.

David Wallechinsky, president of the International Society of Olympic Historians (ISOH), tells CNN Sport: “There wasn’t this huge emphasis that this is it, this is the Olympics.

“In ’48 when the Games came back after 12 years people were just happy to have it happen at all. Of course, the introduction of the television, when people could watch it live, or at least follow a daily report, in the ‘60s, it was a whole other deal.

“By the time you got to 1968 you only had to follow what happened to the non-violent the protest of Tommie Smith and John Carlos to see that there was international interest in the Olympics.”

The future

Whenever an Olympics is held, there seems to be a crisis. In 2012 there were security issues, in 2016 it was the Zika virus. Now in 2020 it’s the coronavirus.

Last week, Japan’s deputy prime minister even went as far as to tell a parliamentary committee last week that Tokyo 2020 was “cursed,” arguing that the Olympics is stopped by extraordinary world events every 40 years.

The Olympic movement has survived much: the boycotts of 1980 and 1984, the tragedies of Munich 1972 and Atlanta 1996, but in the last 100 years the world has not experienced something like the coronavirus pandemic.

“We [the media], in the run up to the Olympics are always looking for the negative because that’s a good story,” says Wallechinsky.

“To tell people in 2012 that everything in London is going great, that’s not a good story. Even the best organized Olympics, like Sydney in 2000, there’s always these negative stories in advance and whenever I’ve spoken to people in organizing committees I’ve warned them about this – it’s not you, it’s us – but sometimes these warnings are real and in this case they are.”