A bill that would change the way songwriters in the music industry are paid in the digital age is in the final stretches of becoming law.

In a Congress that’s divided on most hot-button issues, the Music Modernization Act passed the Senate by unanimous consent last week after the House passed its version of the bill in April.

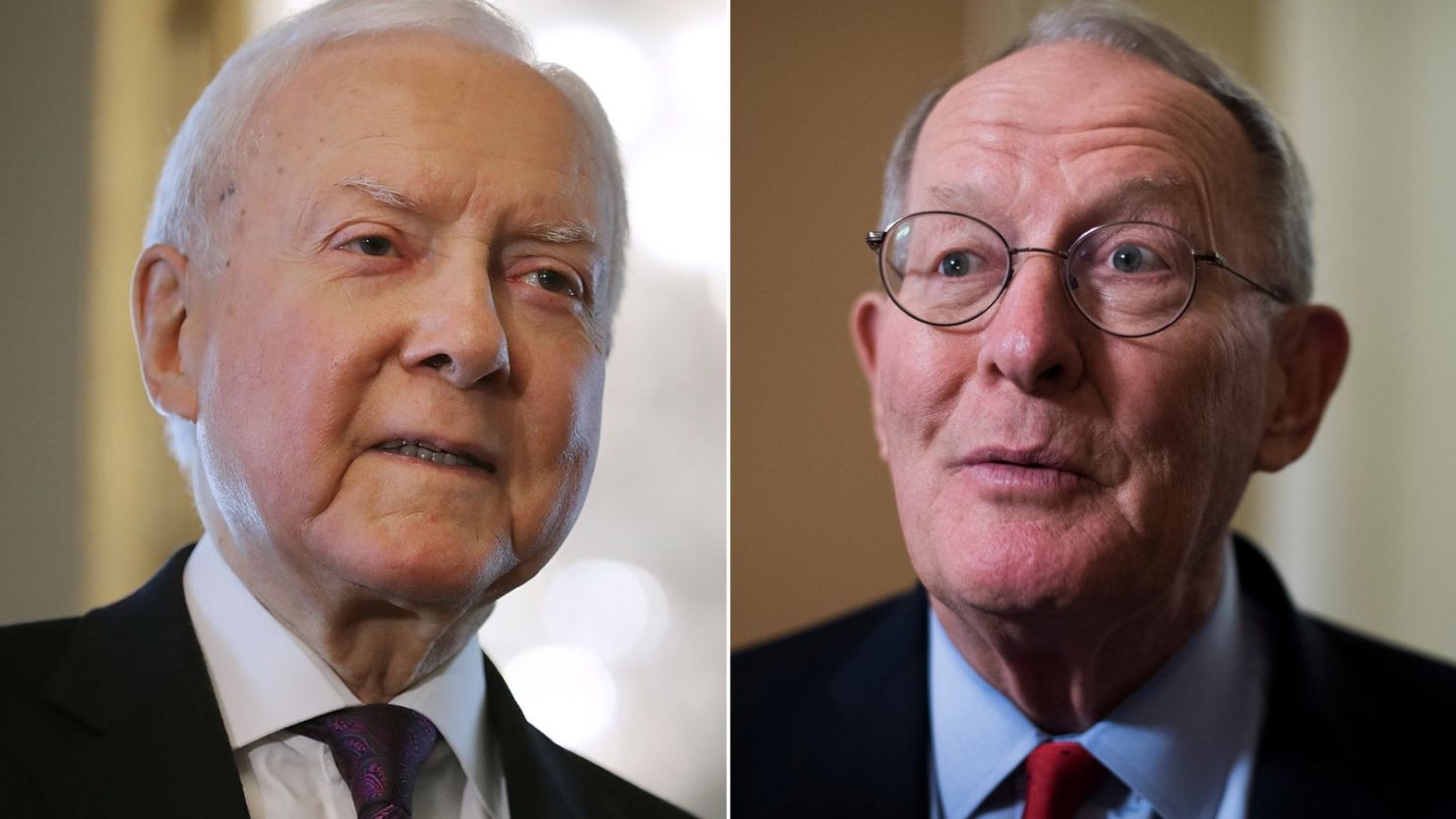

A co-sponsor of the bill, Tennessee Sen. Lamar Alexander, told CNN he expects the House to approve the Senate’s version of the bill this week, though as of Sunday a vote on the House bill had not yet been scheduled. The House majority leader’s office declined to comment to CNN for this story. The bill’s supporters say the goal is for President Donald Trump to sign the bill into law by the start of October.

If passed, the Music Modernization Act would be the first overhaul to music copyright law in decades.

The bill, co-sponsored by Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch who is a songwriter himself, would overhaul the laws related to how songwriters are paid when their songs are licensed or played. The act would also allow artists to receive royalties for songs recorded before 1972.

Another key aspect of the legislation is that it would create a separate entity, overseen by publishers and songwriters, ideally making it easier for them to be paid the royalties they say they’re owed when their songs are played on the internet. Digital music providers, like Spotify or Apple Music, will have the chance to obtain a blanket license, with the goal of stanching lawsuits over copyright infringement.

Hatch said in a statement last week that the bill is a “historic reform for our badly outdated music laws.”

“The Music Modernization Act provides a solution, and it does so in a way that brings together competing sides of the music industry and both sides of the political spectrum,” Hatch said.

Independent songwriters have criticized the bill for giving too much power to major music publishers, arguing that its highly unlikely independent writers will get their fair share when their songs are streamed.

SiriusXM also objected to the part of the bill that would require them to pay royalties for songs before 1972 while not subjecting radio broadcasters to the same requirement. In an op-ed for Billboard, SiriusXM CEO Jim Meyer called it “bad public policy to make a royalty obligation distinction between terrestrial radio and satellite radio.”

But the company endorsed the bill after last-minute negotiations, which included getting their royalty rates to hold for nearly another decade.

Alexander’s involvement in the legislation came from the concerns of his constituents in Nashville, a municipality colloquially referred to as Music City, where the senator said “the city is full of songwriters as Napa Valley is full of winemakers.”

“It’s just a matter of fairness and to keep these songs coming,” Alexander said.

But Alexander also got a “personal lesson on how little you get paid even for a song that gets published and recorded by a pretty well-known” artist.

The Tennessee senator, who can play the piano, has been receiving royalties for country artist Lee Brice’s 2010 song “Falling Apart Together,” about a couple trying to make ends meet. Alexander said he reported $136.75 in song royalties to the Senate Ethics Committee last year.

Hatch himself has reportedly written over 300 songs, including patriotic songs and religious hymns and even a Hanukah song at the suggestion of The Atlantic. In a video posted earlier this year, Alexander played one of Hatch’s songs on the piano to promote the bill.

Before the bill was passed, the Senate renamed the bill the Orrin G. Hatch Music Modernization Act, honoring the Utah Republican. Alexander said Hatch, who is retiring from Congress at the end of his term in January, was “very moved” by the gesture.

“He said, ‘You didn’t have to do that, but I appreciate it very much,’” Alexander said.