In Finland, scientists are making an entirely new ingredient out of air, water and electricity – and they hope it could revolutionize the way our food is produced.

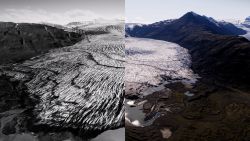

Feeding an ever-growing population is putting a huge strain on the Earth’s resources. Agriculture is one of the world’s largest sources of greenhouse gases, with animal farming in particular responsible for 14.5% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, mostly from beef and dairy cattle.

On top of that, farming uses vast areas of land that might otherwise be home to carbon-storing forests; it also guzzles huge amounts of water – up to 70% of water-use worldwide, according to the OECD.

But a Helsinki-based company is trying to change that.

“In order to save the planet from climate change, we need to disconnect food production from agriculture,” says Pasi Vainikka, CEO of Solar Foods.

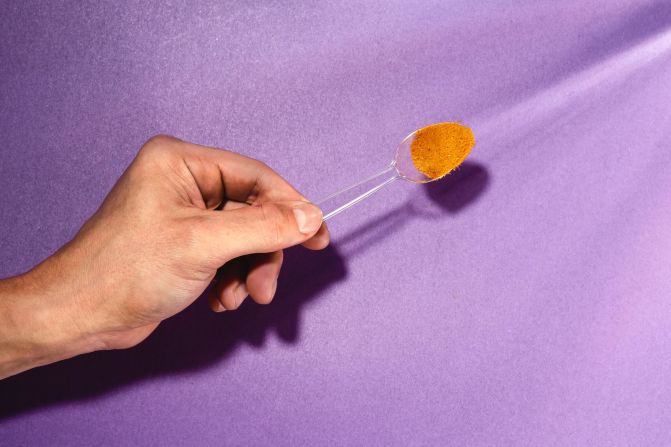

Protein powder

At its pilot plant, the start-up is developing a new natural source of protein it calls Solein. Like other protein supplements, it has no discernible taste and can be added to almost any snack or meal. But Solar Foods says its product will have have a tiny carbon footprint.

Meat substitutes are going mainstream

Solein is made by growing a microbe in liquid in a fermentation tank. It’s similar to the process used in breweries, but instead of feeding it sugars, as you would when brewing beer, Solar Foods’ microbe eats only hydrogen bubbles, carbon dioxide, nutrients and vitamins.

Read: This farm is growing food deep beneath South Korean mountains

Solar Foods makes hydrogen by applying electricity to water, and sources carbon dioxide by extracting it from air – which is why the company describes Solein as being “food out of thin air.” All this is powered by renewable energy, minimizing the product’s carbon footprint.

“You end up with a powder that is about 65 percent protein and carbs and fats,” Vainikka told CNN.

That powder could be added to things like bread and pasta, or to plant-based meat or dairy substitutes. One day, it could even be used as a food source for lab-grown meat, he says.

Solar Foods claims production of Solein is 100 times more climate friendly than meat and 10 times better than plant-based proteins, as well as using much less water.

Scaling up

The company was founded in 2017, made up of former scientists from Finland’s national research institute.

Read: Check into a growing crop of vegan hotels

Its pilot plant is able to produce about a kilo of dry protein powder per day, and Vainikka says it can match the price of existing plant or animal protein ingredients, with “a production cost of $5-$6 per kilogram of 100 percent protein.”

It aims to have Solein on the market and in millions of meals by 2021, but before then it needs to scale-up from pilot plant to major commercial production, and Solein needs regulatory approval for human consumption.

Tomas Linder is an associate professor of microbiology at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, not connected to Solar Foods. He believes that proteins derived from microbes have a part to play in feeding the planet while reducing emissions.

He points out that using carbon dioxide as the carbon source means you can produce this kind of food anywhere, and adds that freeing up land from farming means it could be used to let forests recover, which would sequester more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

But Linder cautions that more studies are needed before we can be sure of the carbon emissions associated with these kinds of products. “You also have to consider that at the amount we have to produce, you would need to build huge bioreactors, with lots of concrete and steel,” he says – which would result in extra carbon emissions.

Solar Foods is currently working with the European Space Agency on a way for astronauts to use Solein while in orbit. While that may sound like the realms of science fiction, Solar Foods is keen to point out that its process is natural.

“We are doing the same thing plants are doing, but … we don’t need the sun,” says Vainikka. “Our process is fundamentally more efficient.”