Editor’s note: The UN estimates that around 17 million people born in India live outside its borders. The group is considered the world’s largest migrant population. From the NBA’s first Indian-origin player to the descendant of an indentured laborer, CNN spoke to a handful of people born to Indian parents who settled overseas.

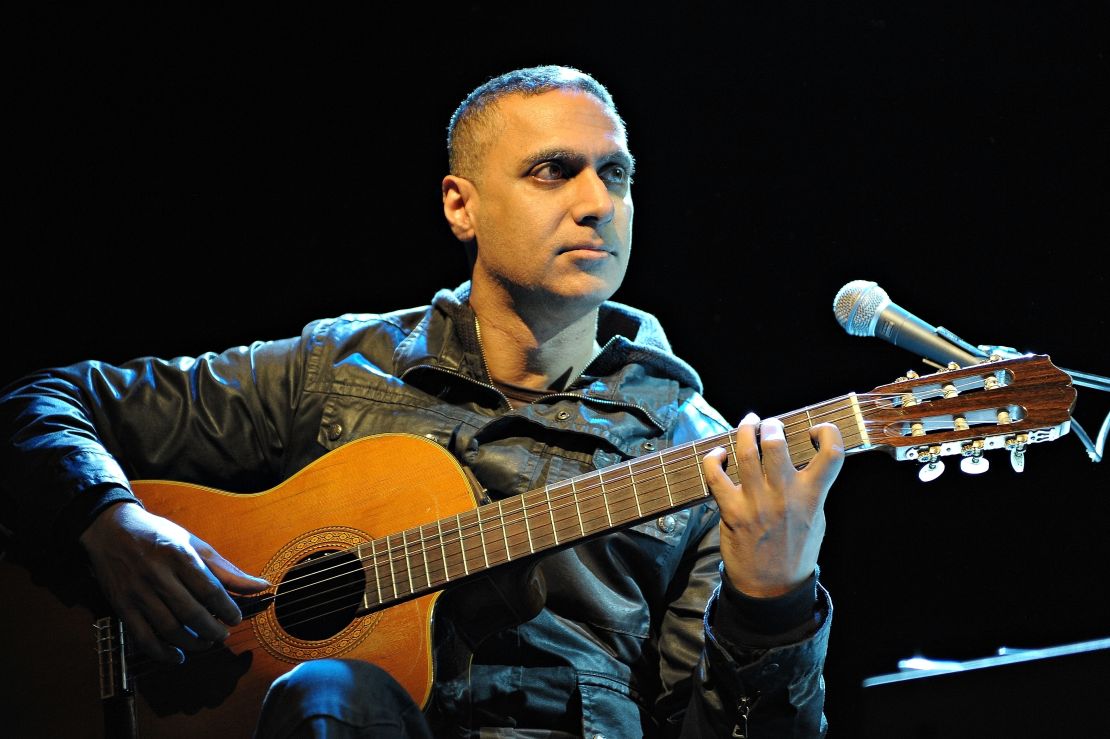

Music producer and composer Nitin Sawhney didn’t think he was “massively different from anyone else.”

That is, until he went to school.

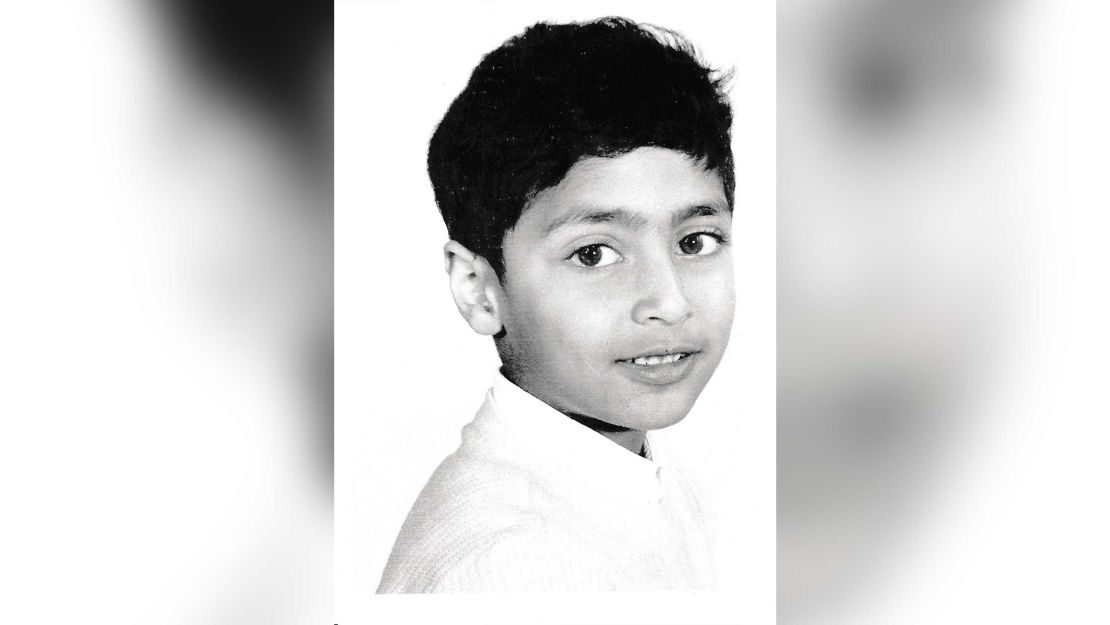

Growing up in the town of Rochester in southeast England, Sawhney witnessed the rise of the far-right National Front party, and first encountered racism when he was just five years old.

“Vans followed you home from school, shouting out racist abuse,” says Sawhney. “I had almost daily attacks when I was between the ages of about 11 and 13. It was a very vicious, xenophobic time to be in school, particularly around my area.”

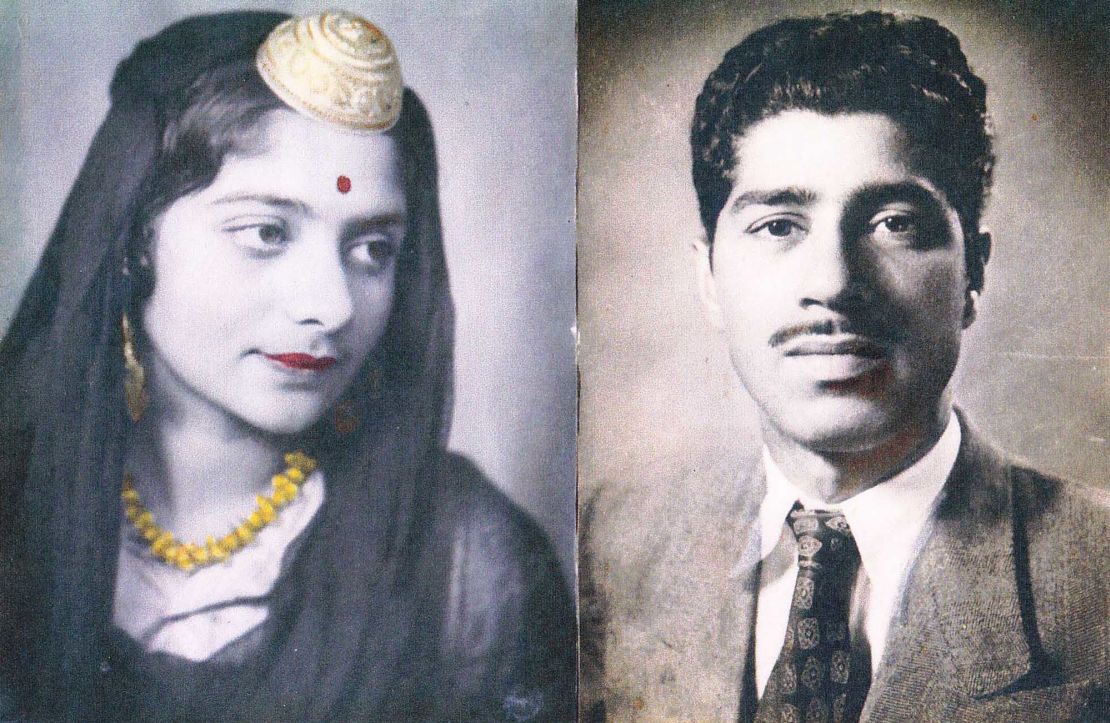

Born to parents who arrived in Britain in the 1960s from the north Indian state of Punjab, Sawhney found comfort in music at home where he was exposed to an array of musical influences.

His father listened to everything from Indian classical to Cuban sounds, while his mother was a trained Bharatanatyam dancer, a traditional Indian art form.

“I’d shut myself in my room and just play for hours, whether it was the piano or the guitar. I did that from about the age of five.”

At the age of 54, Sawhney still sees music as his safe place, but feels more at home in London than he ever has before.

“I don’t know if I’ve ever felt home anywhere. Part of my psychological makeup is that I tend to feel a bit like an outsider in most places. But since I moved to London, I felt that London was my anchor,” he says, citing the city’s diversity and creativity.

Before he focused his attention on music as a career, Sawhney followed what could be considered a more traditional path for Asian children – he studied law and worked in accountancy. “I think those are traditional things that happen with Asian kids”, especially when he was growing up, he says.

Music was his first love but breaking into the industry had additional challenges as a person of color. “There’s a strong sense of white privilege in this industry. I’ve challenged it a lot over the years and I feel that I have made some headway,” he says.

Sawhney was a pioneer of the British Asian music scene in the 1990s and was also one of the writers and performers with the hit Asian TV comedy series “Goodness Gracious Me.”

Having won or been nominated for a host of awards – taking home the prestigious Ivor Novello Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017 – he has won an attentive audience, to say the least.

Sawhney was offered an OBE, or Order of the British Empire, in 2007 but turned it down. “I didn’t want the word empire after my name,” he says, referring to India’s former colonial rulers.

His rejection upset his father, who had a “romantic view” of England shared by many older Indians.

After his father died, a letter offering a CBE, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, arrived in 2018 on what would have been his father’s birthday. So Sawhney accepted and the medal was awarded on his parents’ wedding anniversary.

‘Cultural apartheid’ in record shops

Sawhney has never been concerned with how his unique blend of different music traditions would be received, because “that’s my language.”

But music that does not fit into a fixed category should not be palmed off as “world music,” he says.

“When I used to go into record shops, I felt it was used as an excuse for cultural apartheid. I didn’t ever find it was a term of use, it was a term to constrict people’s thinking and create prejudice, rather than to help people understand other cultures.”

Sawhney doesn’t believe in labels in general. “I find labels that classify people by nationality strange because it’s just an accident of birth. It doesn’t make any sense, in terms of how we define ourselves. We’re defined by experiences.”

Sawhney’s current plans involve creating a school to help equip the next generation of composers with the knowledge and experience of the industry that he has acquired.

“It’s important because you might find the young Mozart or Ravi Shankar… somebody who’s got an incredible ability, who doesn’t get given an opportunity to flourish until they get older.”

His wish is for everyone to feel accepted – and he says that shouldn’t be compromised.

“This country is multicultural, it is pluralistic, we have an incredibly diverse culture that makes me proud to feel that I’m living in London.

“At the moment, there are a lot of people who have a very strong determination to make people like me feel unwanted and like the outsiders.

“It’s important to resist that and make sure that those people don’t feel they can win.”