Bryce Thomas’ toy prehistoric reptiles nosedived into the cold, soapy tap water in the kitchen sink, scooping up schools of imaginary fish, when his mother started weeping in the living room.

“If I don’t advocate for him, the city isn’t going to advocate for him,” Shakima Thomas cried. “I don’t trust they’re doing everything they can, and I don’t trust that they ever will.”

The water 5-year-old Bryce loves could have profound effects on his health. Though human skin does not absorb lead from water, Thomas fears Bryce could accidentally ingest the water that flows into the family’s home while playing. He’d just helped his mom wash dishes under a filter that reduces lead in contaminated tap water, then tiptoed onto a step stool and plunged his plastic winged animals through the floating bubbles.

Thomas rose to compose herself, another sea of toys around the chair at her feet. She stepped toward the kitchen where Bryce played.

“They’re not advocating for the residents at all,” Thomas said of local politicians. “Forget the adults. What about the children? Who’s looking out for them? He can’t go to the City Council and speak on his own behalf. He doesn’t even know he’s being poisoned.”

New Jersey’s largest city this week began offering bottled water to about 14,000 households that may have been consuming tap water contaminated with lead for months or possibly years – a move residents and water experts said came long after official denials anything was wrong.

City and state officials have sought to assure residents they’re dealing with what they now acknowledge is a problem, but fear and anger continue to simmer.

“It’s a right, not a privilege, to have clean, safe water, and we are committed to that,” Gov. Phil Murphy said Wednesday as he toured a downtown water distribution location with Newark Mayor Ras Baraka; both are Democrats.

The city and state intend “to get this as right, as fast as we can,” Murphy said. “We take this very seriously. We want to be out ahead of this.”

But for many here, that moment already has passed.

The growing crisis in Newark has been compared to Flint, Michigan, where longstanding dangerous lead levels in many predominantly African-American and low-income neighborhoods forced people to rely on bottled water and led to the prosecution of state and local officials.

“It’s once again a case of environmental injustice, a case of environmental racism,” Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, the Flint physician who sounded the alarm on that city’s water crisis, said of Newark.

“It is once again a population of poor, predominantly minority people who are disproportionately burdened by contamination. Flint wasn’t the first example. Newark is not the last example.”

Water crisis pits neighbor against neighbor

The matter of lead-tainted tap water first flickered on the Newark radar nearly a decade ago, when water samples taken from city schools tested above a key federal threshold for safe lead levels. Problematic pipes and fixtures were replaced, but citywide testing in 2017 showed the same problem in a substantial number of homes.

In a city of about 285,000 people who have struggled through extreme poverty, spasms of violent crime and a cash-strapped municipal government, the water crisis has led to tension between concerned residents and supporters of the popular Baraka, a Newark native and son of the poet and activist Amiri Baraka.

“The community is divided on this issue,” said Thomas, a member of the advocacy group Newark Water Coalition and a frequent government critic at City Council meetings and on social media.

“Some of my neighbors support what I’m doing, but most don’t because they feel as though I should not be trying to bring down their black mayor,” said Thomas, who is African-American.

City officials have set up a website where residents can type in an address to see if their properties are affected. And this week, with national attention focused on the issue, they published a lengthy online tip sheet with answers to frequent questions about lead in the water, along with links to local and state health resources.

Still, the mayor’s office did not respond to CNN’s repeated requests for comment.

Meantime, some residents have stopped speaking to neighbors who have been critical of the administration’s handling of the crisis, Thomas said. Others have stopped attending neighborhood events that involve local government critics.

“I feel like what’s right is right and wrong is wrong, regardless if the person is black or not,” said Thomas, a social worker who was born in Newark. “We should be coming together on this issue, but we’re not.”

Newark kids’ blood lead levels are top in state

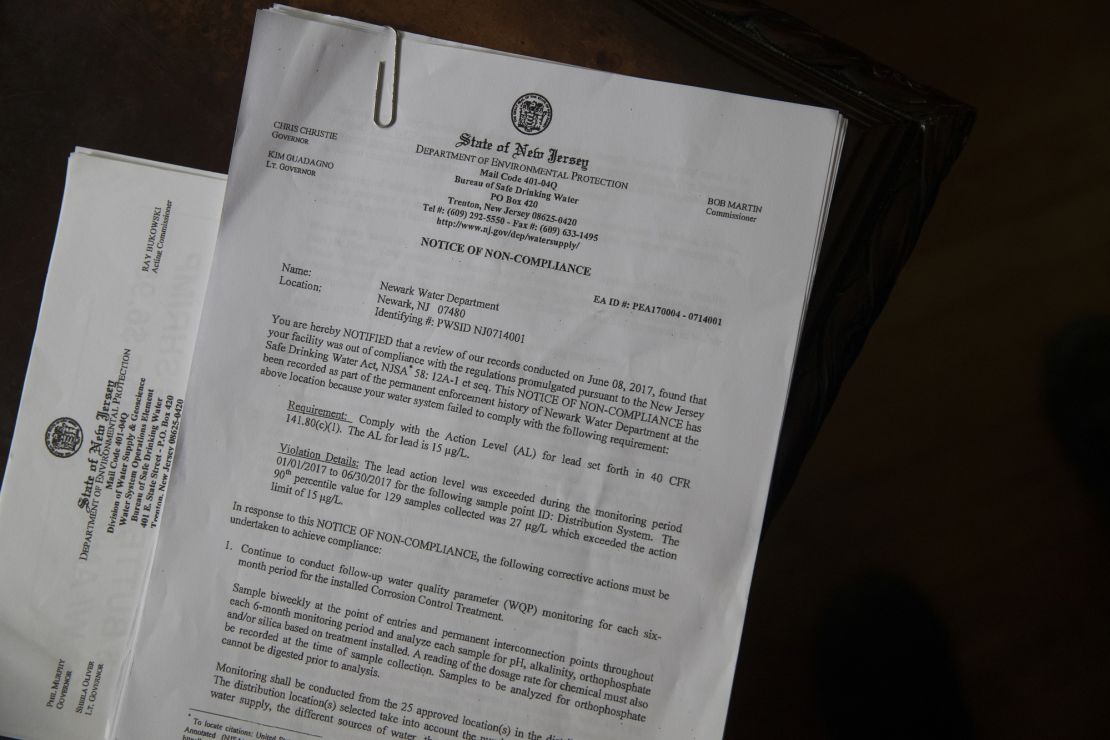

The city tested Thomas’ water in the fall of 2017 for lead and said it was about 9 parts per billion, below the 15 parts per billion (ppb) limit at which the US Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, requires official corrective action to be taken. Thomas learned the result from a letter sent by the city that she shared with CNN.

An independent test about 14 months later, however, showed lead levels of 27 ppb, nearly twice the EPA’s action-level mark, a letter from the testing lab shows.

And in February, the city again tested Thomas’ water and found lead levels of 76 ppb, more than five times the EPA action level, a letter from the city shows.

Though tests showed Bryce had very little lead in his blood, his mother said she fears he may need treatment someday.

Doctors say there is no safe level of lead in drinking water. Even low levels – below the EPA threshold – have been linked to serious, irreversible damage to developing brains, making children and pregnant women most vulnerable. In healthy adults, prolonged exposure to lead is associated with fertility issues, heart and kidney problems, mental dysfunction and high blood pressure.

Newark exceeds every other large New Jersey municipality in the number of children younger than 6 with elevated blood lead levels, according to a New Jersey Department of Health report.

Since January 1, 2018, at least six samples exceeded 30 ppb, and one residence sample showed levels as high as 182 ppb, according to a court document filed by the Natural Resources Defense Council, or NRDC, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group that has taken legal action against Newark.

The city’s lead levels are also among the highest in the nation, the NRDC said.

Newark has said its complex water system supplies about 80 million gallons per day of water to more than 300,000 customers within the city and its surrounding communities.

The city purifies water at two sites: The Pequannock Water Treatment Plant, in West Milford, supplies the North, West, South and Central Wards, while the Wanaque Water Treatment Plant mainly supplies the East Ward.

Water leaving both these plants is lead-free, the city says, and the pipes that transport it, which are mostly made of iron and steel, do not add the heavy metal.

It is only when the water travels through service pipes connecting water mains below the street to homes that lead can enter, according to a city website. Lead may also enter drinking water from the plumbing in individual homes.

Newark water service lines “are owned by individual property owners, from the water main in the street to the water meter in the home,” according to the city website. The typical cost of replacing lines is between $5,000 and $10,000. Under Newark’s Lead Service Line Replacement Program, the cost is expected to be no more than $1,000 per homeowner.

City gives out 35,000+ lead-safe water filters

The NRDC learned in 2017 that Newark had elevated lead levels, said Erik D. Olson, a drinking water expert at the council. But when the group approached city officials to offer help, “we didn’t get anywhere.” In 2018, the nonprofit teamed up with the Newark Education Workers Caucus and began ongoing litigation against the city.

Their federal complaint alleges that the city of Newark failed to install and maintain the corrosion control treatment necessary to prevent water corrosion on service lines and lead plumbing, allowing lead to leach into drinking water.

In a September 17 motion, New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal, a Democrat, argued Newark is in compliance “with the process required for water systems that are no longer deemed to have optimized corrosion control.”

The long-term solution to Newark’s problem is pulling out the lead service lines, according to both the city and the NRDC. As a short-term fix, the Newark Department of Water and Sewer Utilities distributed more than 35,000 lead-safe water filters and cartridges this year to affected residents.

But the EPA said last week that lead levels exceeded the federal water standard of 15 ppb in several samples taken since the filters were distributed.

Newark took the advice of the EPA and on Monday began providing bottled water from four city centers. The action came after months of reassurances by the mayor and others that Newark’s water woes were isolated and the city did not face a Flint-like crisis.

“For us, the most startling issue was the outright denial by city officials,” said lawyer Victor Monterrosa, who lives in the North Ward with his wife and 6-month-old twins.

“You never think it’ll be you. You see water problems in the Rust Belt, so you know Newark might be susceptible to something like this. But you also think, ‘We’re still a big city. We’re still next to New York City. It’s impossible we’re going to end up in a similar situation.’ And we did.”

Not all residents can get free bottled water

At the Boylan Street Recreation Center, one of the city’s bottled water distribution points, some residents in long lines were turned away this week after city officials told them they did not live in areas with high lead levels.

A truck from the city’s emergency management office delivered pallets of bottled water on sweltering Wednesday afternoon. One resident quipped, “Is the expiration date good on these?” referring to an incident one day earlier when city officials did not distribute bottled water that had an expired best-by date.

Edith Tappins, 79, said she was turned away because city officials told her the old water lines in her neighborhood had been replaced.

“I’m still buying my own water,” she said. “I don’t fully trust nobody because the Bible says don’t trust no man. Every morning I say, ‘Lord, bless this water, bless the food.’”

Tappins was with Lorraine Macklin, 68, who hauled away two packages of bottled water in a mini shopping cart. She’d taken the word of city officials and continued to drink the tap water until they reversed course last fall and began distributing water filters, she said.

“They say one thing and they do another, and then they call your house for votes,” Macklin said. “The house I live in is about 100 years old. Our family need this water.”

Hanna-Attisha, the physician who helped expose the Flint water crisis, attended a packed community forum last month in Newark.

“In Flint, we recognized we were in trouble,” she told CNN. “We declared a public health emergency after significant denial and dismissal, but once we knew there were problems, everybody got bottled water. Everybody knew there was an issue. Right now, in Newark, that response has not been comprehensive.”

Newark officials need to declare a public health emergency and take decisive steps to protect residents, Hanna-Attisha said.

“Newark feels like Flint,” she said. “When I’m Newark, I feel like I’m in Flint because this crisis is on top of a community that has already suffered disinvestment and poverty and violence.”

As summer winds down, Thomas keeps a close eye on Bryce whenever he plays with the water – whether it’s the tub filled with toy sharks, in the kitchen sink with his winged reptiles or at the garden hose in the backyard.

“The lead is not visible,” she said. “There’s no smell to it, no particular taste. It’s kind of like an invisible killer. and our kids are being exposed to it every day, every time the water comes on.”

CNN’s Susan Scutti contributed to this report.