If you’d asked me a month ago what I thought I’d be up to on my 30th birthday, being confined to a government quarantine center in Hong Kong wasn’t near the top of the list.

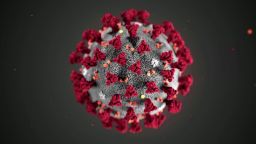

But the coronavirus pandemic has derailed a lot of plans – and even in a city that’s grown used to upheaval, the recent sudden shift in response to a surge in Covid-19 cases has been startling.

For me, it’s meant going from planning holidays and parties, to being escorted from my apartment by hazmat-suited health care workers and driven to a quarantine facility for two weeks of isolation. For everyone else, it’s meant a speedy reassessment of how to respond to a global crisis, on both a personal and societal level – and a new understanding of just how strict the measures to fight coronavirus might have to be.

Holiday camp turned quarantine camp

Life in quarantine – with its regimented meals, temperature checks and PPE-wearing staff – feels like an odd mix of being in school, at camp, and in prison. My facility, in Lei Yue Mun Park, is normally a leafy holiday village in the east of Hong Kong Island. Now, some 100 temporary single-room homes have been constructed in neat rows on an outdoor sports pitch, surrounded by high yellow barriers, housing anyone who the health department decides needs to be isolated after coming into contact with a person who has tested positive for coronavirus.

Since March, that number has surged. Until recently, Hong Kong – which had been fighting the spread of the virus since January – appeared to have it under control, with fewer than 10 new cases being recorded each day. It seemed as though the city’s swift public health measures had worked, infection rates were staying low, and the mask-wearing, hand-sanitizing population could relax a bit.

But relaxing is not the way to control contagion. Almost as soon as revelers started packing bars, restaurants and hiking trails again, the whispered rumors started growing louder – of infected Hong Kongers fleeing Europe and the US, of symptomless spreaders, of a colleague’s sore throat, a friend’s dry cough. Soon, the rumors were borne out by numbers: infections rose from 95 cases on March 1st, to 317 on March 22nd. A long-dreaded “second wave” of the outbreak seemed to be bearing down on the city.

I ended up being covid-exposed after two friends tested positive. I had no major symptoms, which meant I couldn’t get tested myself. But the health department thought I was at enough risk to be taken away for proper isolation and monitoring, while my mildly-symptomatic friends were taken to hospital for tests and treatment, and anyone who’d had briefer contact with them self-isolated at home.

Not that everything about the quarantine process went smoothly. After being told to pack my bags for a long stay, I ended up self-isolating for a week, with no information about how or when I would get picked up. While quarantined friends sent videos of their journeys, rooms and meals, my daily calls to authorities were met with the same answer – there was a list, I was on it, but there had been a lot of positive cases recently, and there was no way of knowing how long I would have to wait, sorry.

And self-isolation was made more complicated by my roommate, who risked infection just by staying in our apartment – not only was I isolating from my friends and colleagues, I had to stay away from her as much as I could too. We ended up only emerging from our bedrooms to pick up food deliveries, wore face masks and rubber gloves on the way to and from the bathroom, and disinfected everything we touched.

So by the time the health department minibus arrived outside my apartment block to take me away two Fridays ago, it was a relief to open the door to a hazmat-suited worker. He stuck a thermometer in my ear in front of my wide-eyed neighbors, and attracted stares from passers-by as we walked down the road. The minibus already had two passengers on it, and picked up another on the way to the camp, which felt like a surprisingly lax approach to social distancing guidelines.

After such a long period of waiting and uncertainty, and a late evening drive across Hong Kong, entering the camp itself felt more like the opening of a film than real life. We passed through security checkpoints manned by more PPE-wearing staff, had another temperature check, then were ushered off the bus into a waiting room for our quarantine welcome briefing. In Cantonese and English, we were told we’d get three meals a day, which we could pick from a menu; that we needed to take our temperature at 8am and 4pm; that we could message one phone number if we had questions or requests, and call another number if we had health issues, or developed coronavirus symptoms. Oh, and that we would all remain at the camp for two weeks – which meant I would only emerge from isolation at midnight on my birthday. It was an unexpected development; but given everything else, that kind of thing didn’t feel important anymore.

The camp was nothing like what I’d expected. Videos from other facilities forwarded between WhatsApp groups showed bare rooms in fixtureless unused apartment blocks, leaky toilets, and barred windows. But when we were led through the barriers to the rows of identical little huts, and given the keys to our temporary one-room homes, it felt like a first night in a cozy university dorm. The room’s new furniture still had its Ikea labels on, and everything smelled of disinfectant. A welcome pack containing noodles, shampoo, shower gel, and toothpaste sat on a desk next to a kettle and hairdryer. Almost as soon as I’d unpacked, a WhatsApp message asked me to pick the week’s food options from the huge menu – a mix of Asian and Western dishes, with vegetarian options, for free. And a sign on the back of the door even addressed the occupants as ‘campers.’

Another surprise was the freedom to walk around outside between the rows of huts – while wearing a mask, of course – to get fresh air and exercise, rather than spending two weeks boxed into a single room. Inmates can even talk to each other, although there are signs around the camp telling us to “avoid gatherings” to “prevent the spread of novel coronavirus”. It’s sound advice (that we could have all probably used a few weeks ago).

Other camp inhabitants who were exposed to coronavirus include bar staff, a flight attendant, and a retired couple living in one of the double-sized rooms opposite mine. There’s capacity for around 130 people, and about half of the rooms were occupied at my last count, although there are arrivals and departures most days.

After more than a week of quarantine living, things have settled into a surprisingly normal routine. Meals are brought around on trollies and carts, and deposited on trays outside our doors. (They’re usually rice, noodle or pasta-based, with some kind of meat or vegetable sauce, and occasional surprises like dumplings – pretty bland, but mostly edible.) Care packages from outside are allowed, so friends and colleagues have sent snacks, drinks and an internet booster to shore up the shaky wifi. Prior to now, I’d already been working from home for three months – so doing the same from a quarantine camp hasn’t made much of a difference. Hong Kong apartments are small enough that living out of one room doesn’t feel like a hardship, and while spot temperature checks and calls from the camp doctor can be annoying, they’re all for the good of my health – and everybody else’s.

Friends in the US and UK have found all of this baffling. If they thought they were covid-positive, they’d be unlikely to get tested, and would be told to self-isolate at home unless they actually needed to go to hospital. By comparison, getting housed in a government facility because you *might* have a *chance* of catching the virus seems like an overabundance of caution. But it’s a testament to how serious the Hong Kong government is about clamping down on cases imported from overseas, and pushing back on local complacency. Anyone who tests positive gets hospitalized, even if they show no symptoms and aren’t a high-risk case – and they stay in hospital until they return two negative tests. Quarantine measures go even further – now, anyone arriving in Hong Kong from abroad must self-isolate at their home or in a hotel for two weeks, monitored by a tracking bracelet.

And the top-down efforts have been matched by Hong Kong residents changing their own behavior – face mask-wearing, hand sanitizing, working and learning from home, and various methods of social distancing have been a normal feature of life here since January. Now, the uptick in infections from a couple of weeks ago appears to be falling again. While Hong Kong’s response may seem heavy-handed to outsiders, and sometimes confusing and impenetrable to the people caught up in it, something is clearly working. This combination of decisive government action and wider social pressure could serve as a model for other countries facing a post-lockdown future – but, as the rest of the world joins Hong Kong’s reality of the past few months, it’s hard to know how many of these changes will become our new normal.

Despite having the longest and most unusual quarantine experience of my friends, I feel very lucky – I haven’t tested positive, I’m not in hospital, camp conditions are good, and I’ve received endless messages of support from family, friends and colleagues. The watchword of the global coronavirus response has been isolation; but I haven’t felt isolated at all, and it seems like the people of Hong Kong have gained collective strength from experiencing all of this together. So, I might be spending my birthday alone; but thanks to the power of mass video calls, I won’t be spending it lonely. And being able to leave quarantine and head back home at the end of it will be the best gift of all.