It was a Chinese dream driven by the same sort of ambition that has seen this country rise from poverty to the world’s second-largest economy in the space of just a few decades.

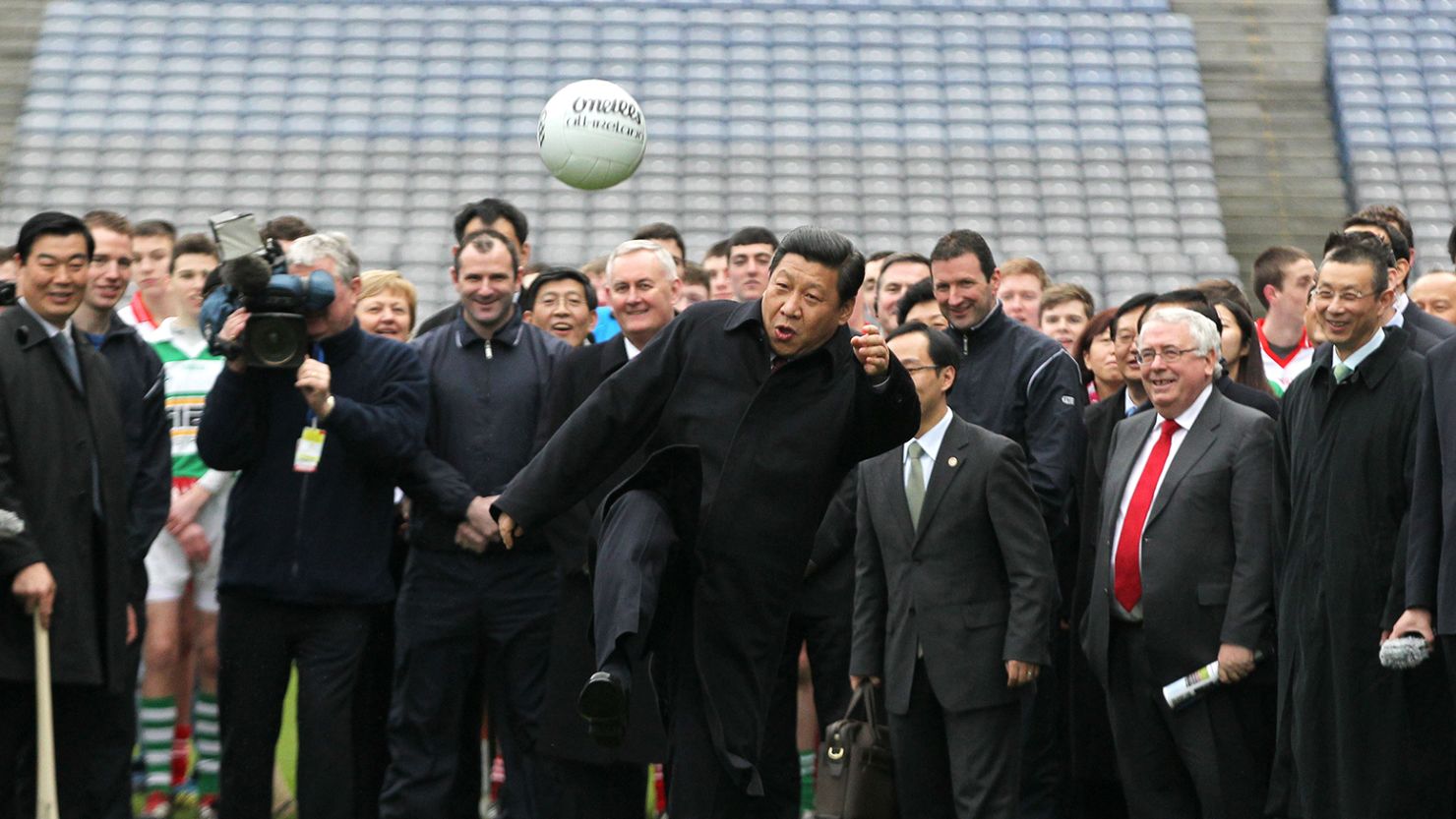

In 2011, around a year before becoming the country’s leader, Xi Jinping outlined a vision to turn China from a footballing minnow to a soccer superpower. He set his sights on the sport’s highest prize of all and outlined a three stage plan for the men’s national team: to qualify for another World Cup, to host a World Cup and to win a World Cup.

For a country who at the time ranked outside the top 70 in the world and had qualified for soccer’s biggest competition only once since its first attempt in 1957, the scale of that task was immense.

Yet few could have doubted Xi’s determination when the Chinese Football Association in 2016 unveiled a plan to make the country a “world football superpower” by 2050.

Backing up those words was a surge in spending that turned the heads of players and fans around the world. State-affiliated conglomerates and developers flush from a property boom flooded the country’s premier domestic competition with cash.

The Chinese Super League (CSL) became a hotbed for foreign superstars seeking lucrative pay days, every big-name signing more eyecatching than the last. Brazilian Alex Teixeira signed to Jiangsu Suning for $54 million; his compatriot Hulk to Shanghai SIPG for $60 million; Oscar, also to Shanghai, for $65 million.

Soon the CSL was rivaling the biggest leagues of Europe in terms of money spent. In the boom year of 2015-16, US$451 million was spent on transfers, taking it into the top five spending leagues in the world.

But more than a decade on from when Xi first outlined his dream, China’s soccer fortunes have fallen as quickly as they once rose. Poor financial decisions and alleged high-level corruption coupled with a three-year pandemic have left the sport in tatters.

When Covid hit the economy and the property market stalled, the funds from state-affiliated firms and developers dried up. Strict pandemic rules meant fewer fans watching live games, and in turn fewer sponsors. Clubs struggled to pay wages; many of the foreign players and coaches brought in to raise the standard of the domestic game upped sticks and quit, many of them citing the government’s onerous zero-Covid stance that had made seeing their families all but impossible.

With the CSL’s 2023-24 season kicking off on April 15 (in a sign of the chaos, the official start date was announced just one week in advance), most teams are still frantically finding replacements.

Many believe that, in truth, the rot had set in long before Covid arrived on the scene, and that the virus “exacerbated the Chinese Super League’s whole financial scenario, accelerating its downfall and making it almost impossible to gain revenue from league sponsors and broadcasters,” according to William Bi, a Beijing-based sports consultant.

But while, like any good game of soccer, the reasons behind the apparent demise of Xi’s dream remain a matter for debate, few could argue with a scoreline that shows the vast majority of the foreign talent brought in to build that vision have voted with their feet.

Here, the stats say it all: Of the league’s all-time top 100 transfer deals, according to the Transfermarkt database, at least 75 were foreigners. Only three of them remain in China.

The gold rush

Few things illustrate Chinese soccer’s trials and tribulations as neatly as the influx of star players, born and raised overseas, who came to the CSL and acquired Chinese citizenship to become eligible for the men’s national team.

The fast-track naturalization of overseas players with family ties to China was seen as a quick way of elevating standards. The ex-Arsenal prospect Nico Yennaris (now known as Li Ke) and ex-Everton player Tyias Browning (Jiang Guangtai), both of whom have Chinese heritage, were among the first to take the step.

More controversial were the naturalizations of five Brazilians – Fernando (who became Fei Nanduo), Aloisio (Luo Guofu), Elkeson (Ai Kesen), Ricardo Goulart (Gao Late) and Alan Carvalho (A Lan) – none of whom had Chinese heritage.

But skeptics will point out that all these naturalizations came during the boom years, when times were good and the money was flowing. During the pandemic every one of those five Brazilians left China – only two have returned. Goulart, who left in 2021 after claiming his team Guangzhou had failed to pay his wages, has even renounced his Chinese nationality.

He is not alone in doing so. Roberto Siucho, who was born and raised in Peru, is another who has had second thoughts. Siucho renounced his Peruvian citizenship to pursue naturalization through his late Chinese grandfather after he transferred to CSL giants Guangzhou Evergrande in 2019.

“It was a really difficult decision, because I knew that once I became a Chinese national, I would lose my chance to be called up for the Peru senior team,” said Siucho, who formally changed his name to Xiao Taotao.

“But I felt it was a good option. I think if my grandfather was alive, he’d have been overjoyed.”

Fast forward a few years and Siucho has renaturalized as a Peruvian and is back with his old club Universitario. He has ambitions of playing for the Peruvian national team.

No one thing led to the decision, he says, rather “a bit of everything.” Even so, there was a clear turning point.

“2019 was a marvelous year in China. My family was able to visit and experience it. Then Covid happened,” Siucho said. “(At one point) I hadn’t seen my family for a year and the rules were you couldn’t bring them in while the borders were closed. A lot of footballers left because of that.”

Covid, a turning point in the game

World Cup winner Fabio Cannavarro – Siucho’s first coach at Guangzhou – expressed a similar sentiment when he gave up $28 million in salary and bonuses to leave his role in 2021, telling state media that “Covid changed everything.”

Other foreign names synonymous with the CSL’s golden years, such as the Brazilian trio of Hulk, Paulinho and Alex Teixeira – who together cost more than $150 million to bring in – also left via free transfers or mutual termination. Texeira gave up his naturalization application and Paulinho, widely seen as one of the greatest ever CSL players, explicitly cited Covid in his decision to leave.

China’s strict “zero-Covid” policy had meant clubs were required to train and compete in “bio-secure” venues that players were unable to leave for months at a time.

“It was difficult mentally, not being able to leave or do anything. But it was the only way we could continue,” Siucho said.

Amid all the outbreaks and lockdowns, fixtures were often postponed, leading to further frustration. When games were played, they took place in front of empty stadiums devoid of atmosphere. Homesickness set in for many players.

“For three years, I hadn’t enjoyed being a husband or father. I got to see my family after nine, 10 months sometimes. That’s not the life I want,” said John Mary Honi Uzuegbunam, a Cameroonian international who played for the CSL team Shenzhen FC and second tier Meizhou Hakka from 2018 to 2022. He missed the birth of his first child, his twins, and their first two birthdays.

“That feeling was so awful, coming back home from training all alone. You look at pictures of your family on your phone and think, ‘goddamn, I’m a married man, I have kids, what the hell is going on?’”

Mary now plays for Caykur Rizespor in Turkey.

The money dries up

While Covid restrictions were making life a misery for many of the players, the pandemic was creating havoc for the firms bankrolling their salaries.

The Evergrande Group, whose collapse in 2021 sparked the country’s worst property market crisis on record, spiraled from the Chinese government’s crackdown on the sector. Its affiliated men’s soccer team, Guangzhou Evergrande, was unable to fully pay player wages and in 2022, the two-time Asian champions were relegated from the Chinese Super League.

“Chinese football changed, a lot of the teams were in financial crises. Even Guangzhou, one of the best teams in China, was encountering difficult situations. It was complicated,” Siucho said.

Empty stadiums not only hit gate receipts, but sponsorship deals too. And with the country’s economy having taken a hammering, conglomerates and property developers simply had less cash to splash around.

Not all the problems were down to Covid; some were simply bad business decisions. In a bid to foster local talent, the Chinese Football Association (CFA) in 2017 raised taxation on overseas signings – any club that spent more than US$7 million would have to pay an equal amount to the CFA. Clubs responded by drastically tightening their wallets, which in turn hit fan turn-out and sponsorship interest.

The consequences of all these forces combined are hard to overstate. Club after club was forced to shut down as they struggled to balance the books or keep up with their superstar wages.

Among the most high profile failures was Jiangsu Suning, which folded in 2021, citing financial problems just months after being crowned league champions. The following year Chongqing Liangjiang head coach Chang Woe-ryong made an emotional apology that the club was unable to pay staff. In January, Wuhan Yangtze became the first team in 2023 to withdraw from the league, the sixth since the beginning of the pandemic and one of more than 35 across all divisions. In February, seven ex-Shenzhen players and coaches filed appeals to FIFA regarding unpaid wages.

And in March, Guangzhou City failed to meet the financial requirements to play in the new CSL season. Hebei FC, meanwhile, has even conceded it struggled to pay water and electricity bills, let alone wages.

‘A complete embarrassment for China’

Bringing foreign talent into the CSL wasn’t just about naturalizing foreign born stars, but raising the level of soccer local players were exposed to in the hope this would in turn filter through to the national team.

The slide through the rankings of the men’s national team shows that hasn’t happened, even if a new head coach in Serbian Aleksandar Jankovic has been appointed in an effort to turn things round.

Meanwhile, the comparatively underfunded women’s team is perhaps Chinese soccer’s only silver lining; the world No. 14 team won last year’s Asian Cup and is considered a dark horse for the Women’s World Cup in July.

Likewise, China’s chances of hosting the World Cup seem similarly far-fetched for the moment, given the various alleged corruption scandals to have emerged in Chinese soccer.

The Communist Party’s anti-graft watchdog is currently investigating a host of CFA figures, including former president Chen Xuyuan, former vice-president Yu Hongchen, former head coach Li Tie, former secretary-general Liu Yi, former CSL general manager Dong Zheng, former CFA disciplinary committee head Wang Xiaoping, and others.

As if that weren’t enough to give FIFA pause for thought when considering any future bid by China, the country’s sole FIFA representative Du Zhaocai recently lost his seat. In April, Du became the latest to be pulled up for investigation for “suspected violations of discipline and law”, with the government assigning a seven-member taskforce to lead the CFA in the meantime.

In a sign that even the fans may have made up their minds, a segment featuring a popular actor lambasting the men’s team on the Chinese social media platform Weibo last year received hundreds of millions of views.

The footage followed a string of losses by the men’s team, including a 3-1 defeat to Vietnam that ended their hopes of qualifying for the 2022 World Cup, and featured Gong Hanlin railing against overpaid entertainers in a rant directed toward China’s rubber stamp parliament, the National People’s Congress.

“A football team with an annual income of 3 million, 5 million or even tens of millions, and they barely see a goal on the pitch,” Gong rants in the clip. “This is a complete embarrassment for Chinese people.”