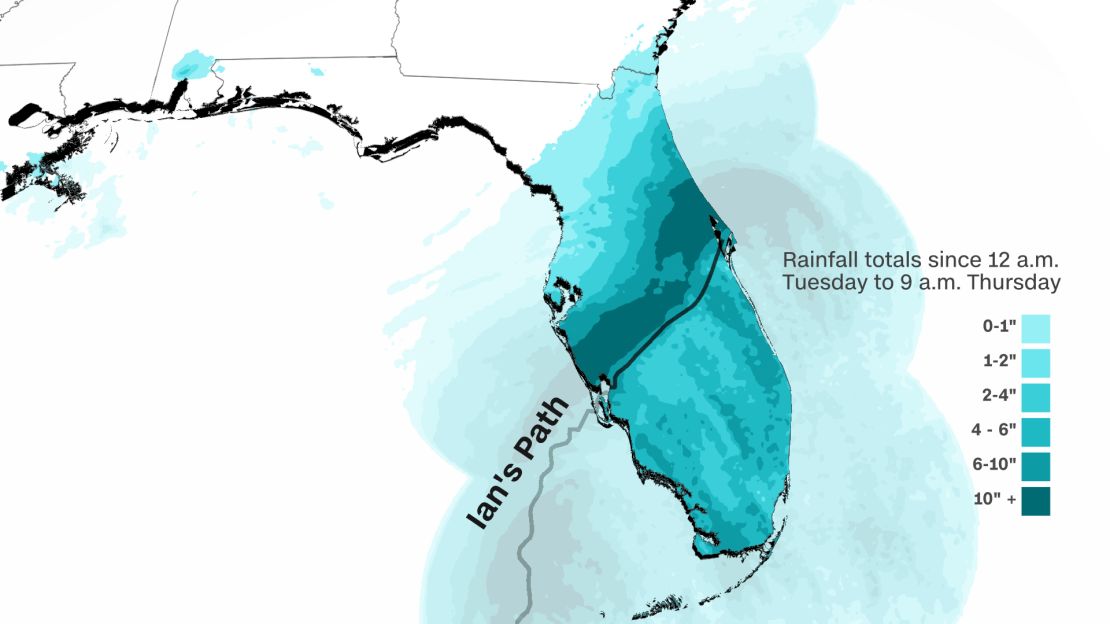

Hurricane Ian slammed into the Gulf Coast of Florida on Wednesday with record-breaking storm surge and devastating winds. But as it tracked inland, extreme rainfall became the most destructive aspect of the storm for central Florida.

Radar estimates suggest well over 12 inches of rain fell in just 12 to 24 hours in a wide swath from Port Charlotte to Orlando. In some of the hardest-hit locations, Hurricane Ian produced 1-in-1,000-year rainfall, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Live updates: Rescuers pull victims from roofs

A 1,000-year rainfall event is one that is so intense it’s only seen on average once every 1,000 years – under normal circumstances. But extreme rainfall is becoming more common as the climate crisis pushes temperatures higher. Warmer air can hold more moisture, which loads the dice in favor of historic rainfall.

Locations in Florida that experienced a 1,000-year rainfall event from Ian:

- Placida – just north of where the hurricane’s eye made landfall – received more than 15 inches of rain over the course of 12 hours on Wednesday. This exceeds the city’s 1-in-1,000-year rain event of 14.0 inches.

- Lake Wales, which is east of Tampa in central Florida, reported nearly 17 inches of rain within 24 hours, exceeding its 1,000-year rain event of 16.8 inches.

Several other locations likely experienced 1,000-year flood events based on radar estimates, including Winter Park (12 inches in 12 hours); North Port (14 inches in 12 hours); and Myakka City (14 inches in 12 hours).

10% wetter

Hurricane Ian’s rainfall was at least 10% wetter because of climate change, according to a rapid analysis released Thursday by scientists at Stony Brook University and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The analysis used the same methodology as a recent peer-reviewed study that looked at the influence of climate change on the 2020 hurricane season.

Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley who ran the analysis, noted that the physical relationship between air temperature and water vapor would suggest that Hurricane Ian’s rainfall should have only been around 5% higher due to climate warming.

“This means that the storms are more efficient at precipitating the available moisture,” Wehner said in a statement. He also cautioned that their result is a “conservative estimate.”

“Climate change didn’t cause the storm but it did cause it to be wetter,” Wehner said.

Stronger storms

Scientists are very confident that climate change is increasing rainfall rates – how hard the rain is falling – and the amount of rain a storm can produce.

It’s also making storms stronger and pushing them to intensify faster. Hurricane Ian strengthened rapidly Wednesday morning as it approached Florida. The storm’s maximum wind speed increased by 35 mph in less than three hours, going from a Category 3 to a strong Category 4 in the process.

Despite being squarely in hurricane territory, major hurricanes – Category 3 or stronger – are uncommon for this part of Florida. When Hurricane Ian made landfall Wednesday with maximum winds of 150 mph, it tied 2004’s Hurricane Charley as the strongest storm to make landfall on the west coast of the Florida Peninsula.

This rapid intensification – a hurricane’s winds strengthening rapidly over a short amount of time – is something scientists say is historically rare but is becoming more likely as ocean temperatures increase, giving hurricanes more fuel to strengthen.

“Climate change is increasing both the maximum intensity that these storms can achieve, and the rate of intensification that can bring them to this maximum,” Jim Kossin, a senior scientist at the Climate Service, previously told CNN. Kossin noted that Hurricane Ian, which rapidly intensified before hitting Cuba and before landfall in Florida, was a good example “of very rapid intensification, and there have been many others recently.”

In pictures: Hurricane Ian slams the Southeast

Higher storm surge

Storm surge is generated mainly by the hurricane’s strong winds, which blow from the ocean toward land and push huge amounts of water beyond the coast.

And although hurricanes are rated based on their wind speeds, storm surge is their most deadly aspect. Around 90% of hurricane-related deaths are water-related, according to the National Hurricane Center, and around 50% are caused by storm surges.

In the region south of Hurricane Ian’s eye – including the Ft. Myers and Naples areas – storm surge swelled to record levels. In Naples, water levels climbed 2 feet above record level early Wednesday afternoon before the gauge stopped working.

Collier County Commissioner Rick Locastro told CNN that his county, which includes Marco Island and Naples, was hit hard by storm surge, calling Hurricane Ian “a totally different hurricane.”

“We survived Irma and other hurricanes, which were more about the wind and yes, always water. But storm surge is something that we have not seen here to this intensity ever,” Locastro said. “We experienced every inch of that storm surge, in some areas well over 12 feet.”

A sea level rise of only a couple of inches can make a dramatic difference in how far inland a hurricane’s surge can travel. Since 1880 – before the industrial revolution and widespread burning of fossil fuels – global sea level has risen on average 8 to 9 inches. Two-thirds of that increase has occurred in just the last two and a half decades, driven mainly by the rapid melting of the world’s ice sheets and glaciers.

CNN’s Allison Chinchar and Rachel Ramirez contributed to this report.