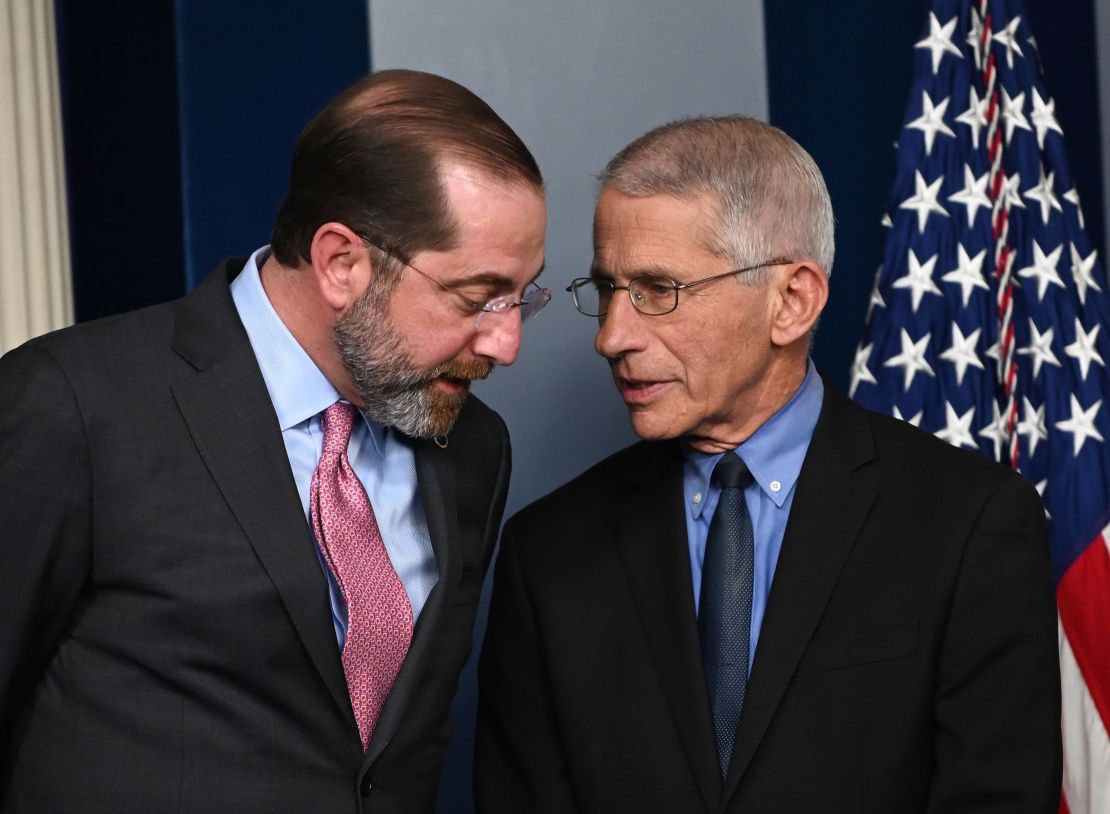

As Covid-19 devastated the workforce at some of the nation’s largest meat-processing plants, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar told lawmakers recently that workers’ lifestyles exacerbated the spread of the disease inside the plants.

Azar’s observation, made during a call with members of Congress late last month, suggested the spread was not due to conditions inside the plant, according to a source familiar with the comments.

Azar told a bipartisan group of lawmakers on the April 28 call that the “home and social” aspects of workers’ lives have played the greatest role in accelerating outbreaks of coronavirus among meat-packing employees, the source said. But it was not the first time a top Trump administration official had faulted workers; Azar and other members of the coronavirus response task force have repeatedly credited the living conditions of these employees with sparking the coronavirus outbreaks, rather than conditions at the facilities themselves, two sources told CNN.

Democratic Rep. Abby Finkenauer, who represents many meat packing employees in her Iowa district, says Azar owes her constituents an apology for his “disrespectful” and “out of touch” comments.

“I am heartbroken to hear somebody to talk like that about people who are working their tails off every day, quite literally putting food on his table,” Finkenauer told CNN in a phone interview Thursday afternoon. “For him to place the blame on my constituents versus the employers who knew for weeks what was going on and yet did not take the proper precautions to protect the folks who show up there every day, work hard every single day, it is unfathomable to me and again shows the disconnect between this administration and what is really happening on the ground.”

Rep. Annie Kuster, a New Hampshire Democrat, called the Trump administration’s handling of Covid-19 outbreaks and treatment of working conditions “deeply troubling,” and said Azar was attempting “to make the case that meat processing plants should be kept open and that workers are at greater risk of COVID-19 infection in their ‘home and social’ environments rather than on the job.”

“This pandemic requires a comprehensive, evidence-based approach to identify risks and protect the health of everyone – this means workplace safety protocols (physical distancing, personal protection) as well as expanded testing, community tracing, treatment, and supported isolation for anyone who may be at risk of spreading the virus,” Kuster said in a statement.

Michael Caputo, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, said in a statement Thursday that lawmakers who discussed Azar’s comments on the April 28 call had mischaracterized them.

“Congressional conference calls are an important part of President Trump’s all-of-government approach to defeating the coronavirus and getting Americans back to work. It’s also important that they are not used as political tools to misrepresent what was actually said,” Caputo said in the statement.

“During this call, which was to discuss the rural allocation of the Provider Relief Fund, Secretary Azar simply made the point that many public health officials have made: in addition to the meat packing plants themselves, many workers at certain remote and rural meatpacking facilities have living conditions that involve multifamily and congregate living, which have been conducive to rapid spread of the disease,” he added. “This is nothing more than a statement of the obvious.”

Covid-19 has hit the meat-packing industry, where workers often labor in close quarters, especially hard. Nearly 8,000 workers have tested positive and at least 27 have died, according to the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union. Those numbers continue to climb each day, with companies deploying more testing resources at their plants in an effort to reopen or remain operational under pressure from the federal government.

The rampant outbreaks have disproportionately hit minority communities as well; nearly two-thirds of meat-packing plant workers are people of color, and roughly half are immigrants.

In addition to Azar and the task force members, some state officials have cited factors outside of the workplace as drivers of infection rates inside the meat-processing plants.

On a call with Vice President Mike Pence, governors, and members of the meat industry last week, Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts, a Republican, said a challenge for his state’s meat producers is that English is “not always the first language” and there are “folks living in higher concentrations with multiple generations.” He then outlined specific steps they’re taking in Nebraska to help with this – providing translations and working to help provide families of workers with alternative places to stay.

And Gov. John Carney of Delaware, a Democrat, said a big issue contributing to outbreaks among Delaware poultry workers is commuting habits, with workers often traveling to work “four and five to a car” or “crowded on buses,” something his state is taking steps to address.

As a possible solution, Azar on the call suggested deploying additional law enforcement officials to areas around the plants to maintain social distancing, according to Politico, which first reported the calls. Caputo disputed that claim.

“Secretary Azar did not and would never mention a role for law enforcement,” he said.

Azar’s suggestion that outside forces in the community have primarily caused meat-packing plant outbreaks is not always supported by available data. In South Dakota, for example, the number of cases linked to Smithfield’s Sioux Falls pork-processing plant, one of the country’s largest, makes up more than a third of the entire state’s 2,905 cases.

After a Smithfield spokesperson told Buzzfeed News that the Sioux Falls outbreak was so severe in part because, among the plant’s many immigrant workers, “living circumstances in certain cultures are different than they are with your traditional American family,” the company disputed that it blames the burst of cases on ethnicity.

“We’re proud of the multi-culturalism on display every day throughout many of our facilities, including in Sioux Falls. Our employees are our strength. They come from all over the world and speak dozens of languages and dialects,” the company said in a statement. “Our position is this: We cannot fight this virus by finger-pointing. We all have a responsibility to slow the spread. At Smithfield, we are a family and we will navigate these truly challenging and unprecedented times together. Our employees are the beating heart of our facilities and we are grateful to them.”

Although President Donald Trump signed an executive order on April 28 aimed at keeping meat-packing plants open, many remain shuttered or are operating at reduced capacity. At least six new plants have closed since Trump signed the order. Union leaders have warned the guidelines set forth as part of the order are voluntary and still leave workers who return to the plants exposed to the virus.

This story has been updated with additional developments Thursday.

CNN’s Dianne Gallagher and Kristen Holmes contributed to this report.