Don’t wear a mask unless you’re sick. If you really want a mask, use a non-medical one. Actually, it’s better to wear a mask all the time. You must wear a mask. Even if you are healthy. (But maybe not if you’re the president.)

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) apparent lack of clarity on whether people should wear face masks to help stop the spread of coronavirus is just one of its messages that has confused the public.

Last month, it had to clarify one official’s comments on the asymptomatic spread of the virus. Now it is facing criticism over how it communicated the danger posed by airborne coronavirus particles.

But a number of communication and behavioral science experts say the WHO is definitely not alone in bungling some of its communication around the pandemic.

When British Prime Minister Boris Johnson ditched the nationwide “stay at home” slogan and replaced it with “stay alert,” encouraging people who were unable to work from home to return to work at a time when the UK was still seeing high numbers of new cases, he created confusion that has taken a long time to clear up.

On Wednesday, his Health Secretary Matt Hancock struggled to explain why the government is now telling people to wear masks in shops, but not in other indoor spaces, such as pubs and offices.

In the United States, the guidance on what is and isn’t safe varies from state to state and city to city.

The uncertainty

This muddled messaging is a major problem.

The novel coronavirus spreads when people interact with each other, so clear and consistent guidance on how to behave is crucial and experts say confusion over what to do – and what not to do – is a major problem that could cause real harm.

Because the virus is brand new, some uncertainty is inevitable. And advice may need to change over time.

“The changes can lead to confusion, or even to charges that the experts don’t know what they’re talking about,” crisis communication expert Peter M. Sandman told CNN in an email.

Masks are a good example of this.

Early in the pandemic, there were serious concerns about shortages of protective equipment for frontline medical workers. Some medical professionals also worried that masks could give people a false sense of security and stop them from following social distancing guidelines.

That’s why some public health bodies, including WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, initially said healthy people shouldn’t wear masks.

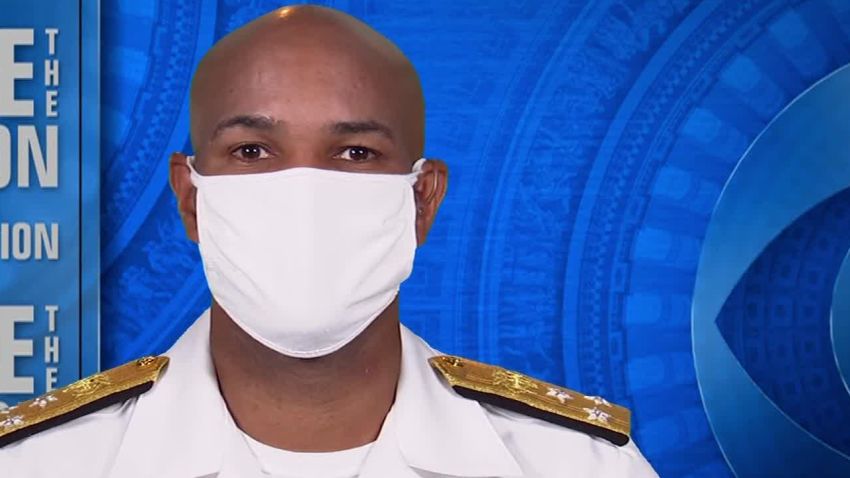

The US Surgeon General Dr. Jerome Adams even went as far as saying masks were “NOT effective in preventing general public from catching coronavirus.”

WHO struck a similar tone. “There is no specific evidence to suggest that the wearing of masks by the mass population has any potential benefit,” Dr. Mike Ryan, executive director of the WHO health emergencies program, said in March.

But Sandman points to evidence from early February suggesting that infected people who didn’t feel very sick were transmitting the virus as they went about their daily lives in public places. At that time, he said, some experts “at least suspected, even if they couldn’t quite say they ‘knew’ it with full evidence-based confidence,” that masks could help slow the spread. “They certainly had no evidence base for claiming they knew it was not the case, which is what they claimed,” Sandman added.

As the world learned more about how the virus was being transmitted, health authorities and governments were forced to change their guidance. Earlier this week, the CDC officially told people to wear masks. But that flip-flopping has caused some people to question the validity of their new advice. Adams himself has recognized that it was “very hard” to correct the message.

There are strategies that leaders can employ to minimize the problem, Sandman said – for example by predicting that some changes may be necessary as more evidence emerges.

Acknowledging the unknown is a key part of successful communication in a crisis.

“A consistent message is sometimes misinterpreted as: ‘Let’s make a bold statement one way or the other – wear masks, don’t wear masks.’ But sometimes that message is: ‘We don’t have the full information,’” said Heidi Tworek, a health communication expert and an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia.

Tworek said explaining the rationale behind the initial mask message would have prevented this confusion.

“In Taiwan, the campaign basically said: ‘Save the [medical grade] masks for the healthcare workers.’ … So you can have a consistent message that says: ‘Masks are important and at this moment they are most important for health care workers and we’re still looking into whether they’re effective against this disease,’” she said.

Shane Timmons, a behavioral science researcher at the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin, said there was sometimes a reluctance among experts and politicians to highlight any uncertainty, for fear of undermining their expertise.

“But what the evidence actually suggests, is that people are very willing to accept uncertainty when it’s specified in clear terms. So if you say, ‘These are the things we know, these are the things we don’t know, this is how we’re going to try to figure it out,’ people will take that on board.”

Sounding overconfident, Sandman said, is “a crisis communication sin.”

The fact that guidance can change as more evidence emerges is nothing new in academic circles.

“What makes it very challenging is that things that usually happen in journals and within small circles of scientists and public health officials – the usual back and forth – are now playing out in front of a global audience,” Tworek said.

Despite being the world’s top public health body, WHO is a relatively small organization with a limited budget. In more “normal” times, it caters mainly to an expert audience. “Its briefings aren’t usually going to this many people, and that makes for a very, very different communication environment,” explained Tworek.

The confusion around the message on masks has caused huge disparities between countries in the willingness of people to wear them – even as experts just about everywhere now agree that face coverings can help stop the spread of the virus.

One influential US model suggests that if 95% of Americans wore face masks in public, it could prevent 33,000 deaths by October 1.

Why are we doing what we’re doing?

But even the most straightforward guidance won’t work if people question its rationale.

“When people understand why they are being asked to do things, they’re much more likely to do it,” said Susan Michie, a professor of health psychology and the director of the Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London.

She points to the “don’t touch your face” and “wash your hands” guidance as an example.

“It’s about stopping the virus that could be on your fingers getting into your body, through your nose, your mouth or your eyes … once people realize that that is how the virus gets into the body, then the not touching eyes, nose and mouth makes a lot of sense to people.”

One of the biggest problems policymakers face when communicating the risks of this pandemic is what behavioral economists call the collective action problem.

For most people, the risk of dying as a result of Covid-19 is quite small. But in order for the pandemic to end, everyone – even those perceived not to be at risk – needs to make sacrifices.

“Clear messaging is one of the key factors in determining whether people are willing to cooperate,” Timmons said.

There may be different motivations. In the UK, the government spoke about the need to protect the National Health Service and save lives. In Ireland, the message was focused on taking care of each other. In some parts of the US, it’s all about preventing another shutdown.

Leading by example

Acknowledging the unknown, providing consistent guidance and “explaining the why” are key ingredients of successful crisis communication strategy. But it doesn’t end there.

“It’s about consistency between what you say and what you do. And this is one of the problems … on the one hand, people are saying ‘Oh, it’s still a risky situation, be very careful,’ and on the other hand, they are opening pubs,” Michie said.

She said public health officials and governments need to get better at joining the dots and providing people with a strategy on how to navigate the situation.

“Think about it as road safety – we have to do our own risk assessment when crossing the road, for example,” Michie said. “Do we always cross the road just on the traffic lights or on zebra crossings, or do we occasionally cross it elsewhere? If we do, we probably consider several things, such as how far away are the cars, what speed are they traveling at, are the roads wet, how agile am I?”

One way to help people make decisions would be a simple coronavirus risk calculator that allows users to put in information about themselves in order to work out what level of danger they are facing and which situations to avoid, she added.

Crucially, Michie said, those in authority must lead by example, and follow their own rules.

Failure to do so risks muddying the message even further – as seen in the US where President Donald Trump’s months-long refusal to wear a mask contributed to the issue becoming a political debate, rather than a factual issue.

Michie cites the example of politicians in the UK who “are saying you need to wear [a mask] when you’re on a bus, but we don’t need to wear it when we’re all squashed together in an indoor space in the House of Commons … the Dominic Cummings [trip] was the pinnacle of this,” she said, referring to a controversial 260-mile car journey made by Boris Johnson’s chief adviser at the height of lockdown. “Undermining your message by saying ‘it’s fine for people to disobey the rules if they’re us rather than you.’”

Photographs of the mask-less British treasury chief Rishi Sunak delivering meals in a newly reopened restaurant – hours after his government told restaurants to make sure their staff wears protection – didn’t go down well, either.

Even the clearest guidance will never hit home if those at the top continue to ignore it.